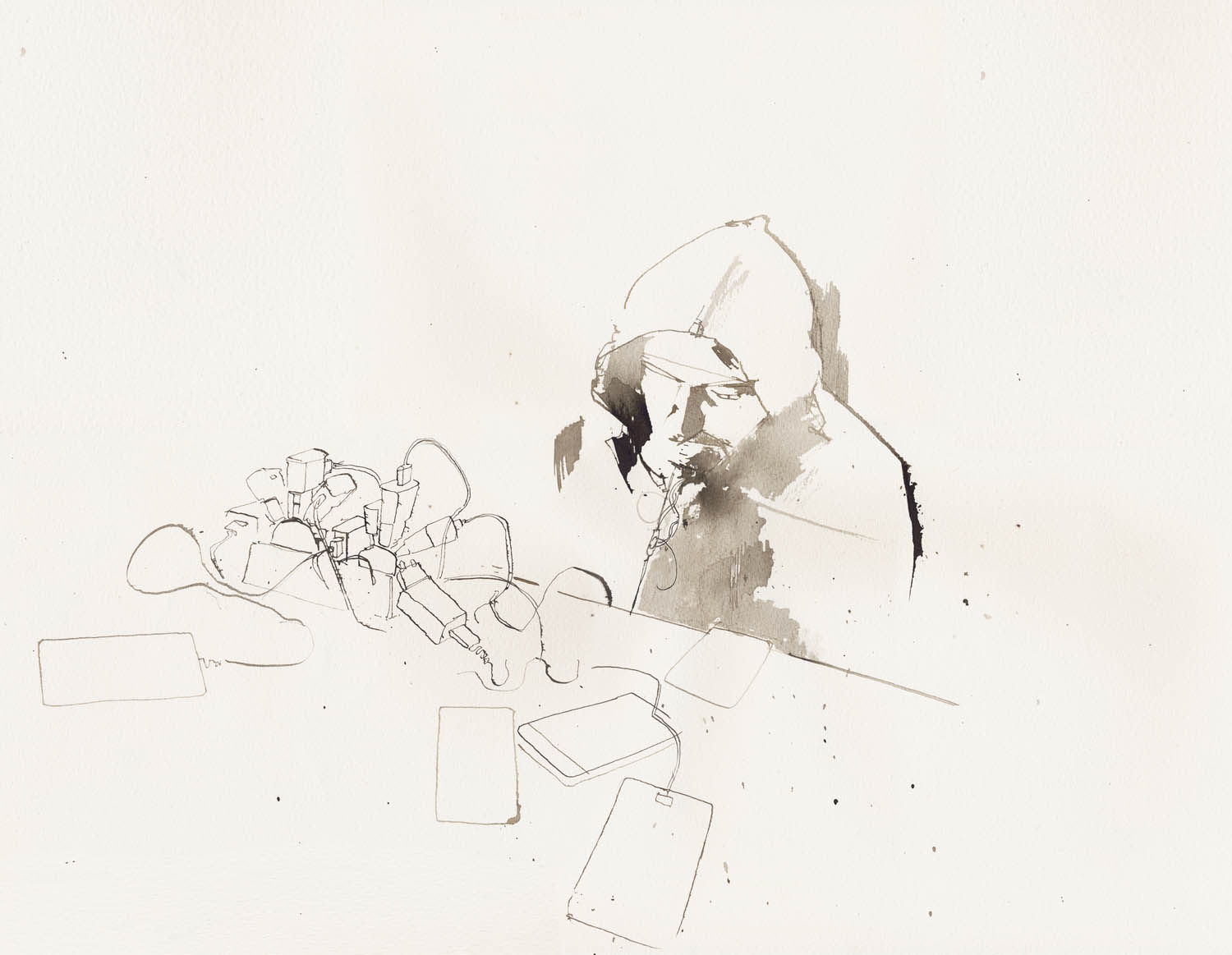

For the 2017 spring issue’s feature project, Paths to Refuge, we asked illustrator George Butler to provide artwork in a couple of ways—spot illustrations for the project’s two reported pieces as well as his own portfolio from the field. In January 2017, Butler headed to Belgrade, Serbia, to observe and depict the conditions of refugees stranded there as a result of border closings along the Balkan Route, one of the main arteries of travel for migrants moving between the Mediterranean and Eastern Europe. When Butler visited, an estimated 2,000 refugees were living amid a cluster of warehouses behind Belgrade’s main train station, trying to survive a brutal cold snap. Médecin Sans Frontière, an emergency-aid group, estimated that nearly half the patients its doctors treated were under the age of eighteen. What follows is a brief conversation that took place after Butler’s return to London, in February.

Why did you choose Belgrade? What was it about this site that compelled you?

Well, the majority of people who’ve arrived in Germany from Syria have been through the Balkan Route. And Belgrade is a common experience, with conditions shared by many refugees—a lot of waiting around, a lot of going to borders and seeing if they can get a lift across, a lot of people waiting to be smuggled. The experience was nightmarish: They were sleeping on the floor, no electricity, no warmth, no food, no anything. The hope—or, rather, the realization—that it’s not all going to be rosy in Europe was beginning to set in. And yet they were sort of too proud to go backward, and weren’t quite sure how to go forward. So here I knew I could find, visually, a group of people who were experiencing the conditions that many refugees experience in Europe—whether it’s in Germany, Sweden, or London. And if it’s not smoke in their lungs, they’re experiencing queuing for food, or being moved around in buses or looking for a place to charge their mobile phones. These are all conditions no matter where you stop along the way.

Were there any resources available to them?

Organizations were trying to bus some people—particularly women and children—back to the refugee camps closer to the border. But a lot of the men didn’t want to go back, because they felt imprisoned in these camps, and they’d rather feel cold and hungry than feel like they’re in prison. So they just stuck it out. The conditions were unimaginable. They burned anything to keep warm—rubber, plastic, old railway sleepers. The smoke was so thick that every time I put my pen on the page and make the paper wet again, an unbelievable, dense smell comes off it; the paper absorbed all the smoke from standing in these spaces. So you can imagine what it’s doing to these guys who were there for three to six months.

When you talk to people under these circumstances, what do you learn about them? Is there a way to paint a general picture, or is it all so varied that it’s unfair to generalize?

I’ve spoken to hundreds of them, and it becomes more and more personal each time. I wouldn’t necessarily describe many of them as refugees in the way we imagine refugees, but I do think there are some fair generalizations. The first thing to remember is that 15 million out of a population of 22 million are still in Syria. And with regard to refugees outside Syria, I found that the majority of people picked up their belongings and thought, We’re going to have to move to our friend’s house, or our parents’, or stay with friends in Turkey, and we’ll wait there for several months and we’ll come back when the fighting has stopped. I think the assumption for a lot of people was that they were going to move for a short period of time until the war ended, and then go back to their homes and carry on. Plans were put in place on that basis.

But now they’re six years on; the expectations are different. People are having to choose, as some of my refugee friends in London have. Rather than say, “I’ll give it another year and I’ll go back to my life in Syria,” people are now saying, “I have to start my life again from wherever I am,” whether that’s in Turkey or in England. It’s a very difficult thing to have to accept, that you may never go back to your country.

What I was trying to empathize with in these drawings is the experience of those lives being turned inside out. Over the course of six years, Syrians in particular have been betrayed by their government and others through a lack of action, and each month that passes, I suspect, will mean that fewer and fewer Syrians will have the chance to go home.

Let’s talk about reportage illustration. What’s your general approach?

Put simply, my job is to tell stories by making drawings. I’m looking for moments in time that I think the audiences can relate to. So these are moments that I think drawing can offer more than a photograph, or film, or poetry, or a piece of writing. They are drawn immediately. The idea is to describe that moment, to tell that story on a single piece of paper with ink. Of course, as simple as that sounds, it can be very powerful if you get it right.

How is that different from what other illustrators do?

The concept is the same: The illustrator is trying to answer a commission, to communicate an idea to an audience. But the major difference is that this is a tool, like photojournalism, used for recording the news. That is something that it was always used for. It’s a proven formula, but it’s just one that we don’t use so often. That’s the theory, anyway.

That raises the question of how you pull it off logistically. Judging by your past work, you’ve put yourself in some unpredictable situations, and yet what you do is so painstaking that you don’t have a lot of time to set up, nor do you have a lot of time to get out of the way.

I think the first thing to do is not to compete with the mechanics of photography. Whether it’s capturing bullets flying on the front line or people getting shot—that is not the objective of this. What I do is find a moment where I’m going to have a more common experience, where the cameras have all rolled on to the front line and I’m left with an hour to sit and draw people in a hospital or draw tanks that were destroyed a week before but now have children playing on them. Some of these are by definition in dangerous places, but because of the people I’m with and because of the situation at that moment, I don’t feel like I’m in danger. It doesn’t feel like a brave thing to be doing. That’s why I think illustration has a place. It’s about capturing a moment over a period of time, an experience that you witnessed and therefore comprehend on a level that other people should be able to understand.

These illustrations are part of a special project on Europe’s migration crisis, Paths to Refuge, which appears in the Spring 2017 issue. Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.