The Second Emancipation Proclamation

Note: Today’s post comes to us from the producers of BackStory. Click here to listen to the interview that inspired it.

——

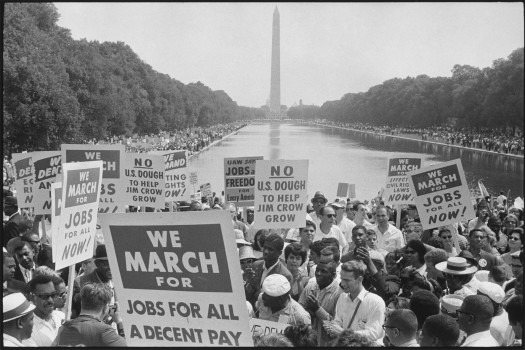

When the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. stood before the Lincoln Memorial fifty years ago today, he began his famous speech with a nod to the Emancipation Proclamation. “Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand, signed the Emancipation Proclamation,” King said, calling it a “momentous decree” that “came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice.”

A century on, that hope had still not fully translated into reality for African Americans, King said—and the March on Washington, of which his speech was the culmination, was part of an effort pushing for the full realization of freedom and equality. But that push wasn’t just a legislative one. Earlier in the summer, President John F. Kennedy had submitted civil-rights legislation to Congress, but it faced a steep uphill climb against staunch Southern Democratic opponents. King had instead been aiming for a different solution—one that looked to the president himself and asked that he not merely celebrate the Emancipation Proclamation centennial that year but issue another one. King sought a second “Emancipation Proclamation”—a presidential declaration that would immediately outlaw all forms of segregation and discrimination in the United States. “This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism,” King said—driving his message home to a very particular audience of one.

“It’s a rich, deep story,” historian and Yale University professor David Blight told us in a recent interview. The stage was set when Kennedy, during his second presidential debate with Richard Nixon in 1960, criticized the slow pace of Dwight Eisenhower’s administration in achieving civil-rights objectives and said that much more could be done. “Equality of opportunity in the field of housing,”—at least those housing programs supported with federal funding, for example—could be achieved “by a stroke of the president’s pen,” Kennedy said.

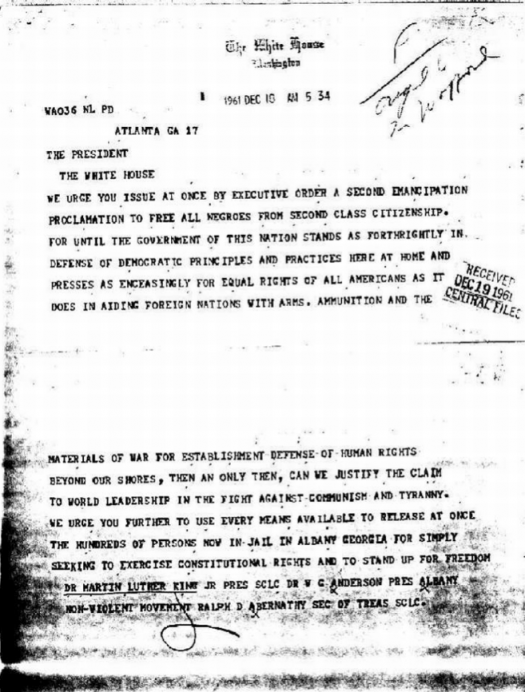

The “stroke of a pen,” of course, was a reference to the president’s ability to issue executive orders—directives that require no congressional input to be implemented. “King and his aides never let him forget it,” Blight says. “Only a matter of days after Kennedy’s inauguration…[they] began to pepper the White House with first telegrams, then phone calls, then letters…”

In June of 1961, King held a news conference in New York calling for strong executive action. Coincidentally, the Civil War centennial was being commemorated across the country. Although King may not have seen how it and the Civil Rights Movement were occupying the same cultural space, his explicit call for a “Second Emancipation Proclamation” connects the two events.

King took the opportunity to press his case in October, when he had a private meeting with the president at the White House. So private, in fact, that the meeting didn’t appear in the president’s appointment book or have any official agenda. “King’s White House visit was deliberately made intimate but hidden, and social,” observed historian Taylor Branch in the Washington Monthlyearlier this year.

During a personal tour of the White House given by Kennedy himself, King seized an opportunity to dramatize his desire for executive action. As they passed by the Lincoln Bedroom, he caught sight of a framed copy of the Emancipation Proclamation—signed in that very room on January 1, 1863. Standing beside it, King pressed Kennedy to issue a second proclamation—outlawing racial segregation by executive decree—and to do so in time for the upcoming centennial of the original. According to King, Blight says, Kennedy’s response was, “That’s an interesting idea. Why don’t you draft something.”

But issuing such a sweeping executive order would hardly be uncontroversial. And it wasn’t clear if it would be constitutional either. The New York Times in June quoted from Herbert Wechsler, a constitutional-law scholar at Columbia, who pointed out that Abraham Lincoln’s executive order had been issued in wartime, and there were still “grave doubts” about its legality until the Thirteenth Amendment was passed. But King and the NAACP lawyers set about building the case for much broader action, drawing on any number of sources to make it.

In May of 1962, King called a press conference to present the fruits of their efforts: “An Appeal to the Honorable John F. Kennedy, President of the United States, for National Rededication to the Principles of The Emancipation Proclamation and for an Executive Order Prohibiting Segregation in the United States of America.” This was “a sixty-five-page manifesto which they hand-delivered to the president,” Blight says, “in which they appealed to the president to issue the second emancipation proclamation.”

Telegram dated December 13, 1961 from Martin Luther King Jr. to President Kennedy: “WE URGE YOU ISSUE AT ONCE A SECOND EMANCIPATION PROCLAMATION TO FREE ALL NEGROES FROM SECOND CLASS CITIZENSHIP.” Source: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

“It is a fascinating document,” Blight says. In an eclectic “preamble” that drew from Woody Guthrie, Frederick Douglass, Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, and even Kennedy’s own words, the “appeal” laid out a compelling vision of American freedom—and the executive action required to achieve it. “We know that freedom is, indeed, a most precious thing,” the preamble began—the part of the document which King most likely wrote. “We know that ‘this land is our land, from California to the New York Island; from the Redwood forests to the Gulfstream waters,’ we know that this land exists for all Americans, white and Negro. However, we also know that to millions of Negroes throughout these United States, freedom is not yet a ‘living reality.’”

“On several occasions you have said the times we live in demand bold, imaginative and courageous action by all our people,” it continued. “We, like you, Mr. President, believe that the time we live in is a time for greatness. The conscience of America looks now, again, some one hundred years after the abolition of chattel slavery, to the President of the United States….We believe the time has come for Presidential leadership to be vigorously exerted to remove, once and for all time, the festering cancer of segregation and discrimination from American society.”

And so then the document got down to business—transforming into a legal brief, making the case for the legality of executive action and the need for Kennedy to undertake it. They cited other executive orders, Blight describes, “particularly the modern ones by [Harry] Truman, that desegregated the military in 1948, or Franklin Roosevelt with the FEPC, the Federal Employment Practices Commission, in 1940, and so on.” They also drew on scholarly arguments for a strong executive that have gained ground in recent years, and on the words of a president who had exuded that expansionary vision: Theodore Roosevelt. King and his advisors drew special attention to Roosevelt’s belief, recounted in his autobiography, that “it was not only [the president’s] right but his duty to do anything that the needs of the Nation demanded unless such action was forbidden by the Constitution or by the laws.” Where the law was silent, Roosevelt said, there was opportunity for executive action.

Though Kennedy as a candidate had talked about desegregating federally assisted housing with “the stroke of a pen,” he had seemed reluctant to do so once in office. Pressed on the issue at a news conference in early 1962, the president demurred. According to Anthony Lewis of the New York Times, “The President indicated his feeling that it was important not to move too fast in the field of race relations so as not to get too far ahead of public opinion.” And so despite the prodigious efforts of King and his team, the initiative seemed to be going nowhere.

By August of 1963, the urgency felt by King and other civil-rights leaders had intensified. That spring, state authorities in Birmingham, Alabama, had unleashed dogs and powerful fire-hoses on peaceful demonstrators, and King feared more such brutal confrontations. With the prospects for comprehensive civil-rights legislation still viewed as bleak, the executive option remained tempting—if only Kennedy could be persuaded to act. According to Blight, King’s invocation of the Emancipation Proclamation in the “I Have a Dream” speech was partially intended to maintain that pressure on President Kennedy; King wanted Kennedy to use his executive powers and spare civil-rights activists a hard, bloody campaign.

So why have we forgotten this aspect of the 1963 March on Washington? Apart from the stirring and optimistic rhetoric of the last four minutes of King’s speech, another event halted King’s campaign for a second Emancipation Proclamation. On November 22 of that year, President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas—ending his young administration, but also opening up a new chapter in civil rights. President Lyndon Johnson, once no friend of civil-rights legislation, now became its greatest champion, drawing on Kennedy’s legacy to build support for, and ultimately pass, the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965. For all of President Kennedy’s personal sympathy toward the Civil Rights Movement, he would be a more effective ally in death than during his presidency. These legislative achievements, after all, would ultimately fulfill the legal goals of the second Emancipation Proclamation King had proposed and help fully realize the moral promise of the first.

For more information: The King Center in Atlanta has an online archive featuring the proposed “Second Emancipation Proclamation.” You can listen to David Blight discuss the second Emancipation Proclamation, and hear more from his interview on this week’s BackStory, which looks at the origins and impact of the 1963 March on Washington.

Editor’s note: The photographs by Leonard Freed are from the book This Is the Day: The March on Washington (Getty Publications, 2013).

About the author: Emily Charnock is an assistant producer at BackStory with the American History Guys. VQR contributing editor Jesse Dukes contributed to this article.