Alice Munro’s Too Much Happiness

Alice Munro is widely recognized as being among the greatest living authors writing in English, and her latest volume of stories, just now being released in paperback, inspires, as the title suggests, almost Too Much Happiness—her thirteenth book in a nearly sixty-year career. The collection reads with the headlong rush of both a thriller and a romance. In ten stories, told with equal power and precision from male and female perspectives, Munro explores how people do and don’t move on with their lives after losing what they thought they couldn’t live without.

A master of psychological fiction, Munro champions the value and complexity of the lives of outwardly ordinary people. She examines the conflicts protagonists experience as they strive to reconcile their need for self-realization—which will differentiate them from those around them—with their desire for approval from peers. Her stories reveal that paradoxically, even community insiders are outsiders, and she frequently uses doppelgängers and “multigängers” to depict the psychological multiplicity characters may feel within themselves, or the connections that exist between different characters in a story.

Above all, Munro’s contribution to literature is her visceral sensibility. She translates the sensation of being alive onto the page. Having lived all her life in Canada, she writes compassionately but unsentimentally about characters who sometimes live in Vancouver or elsewhere, but are most often culturally grounded in small towns in Southwestern Ontario, or “Sowesto.” Yet they are so authentic and universally similar to her readers—regardless of where we hail from—that they seem to live and breathe through us, and we through them. We stand revealed as Munro unmasks ambivalent feelings between parents and children, husbands and wives, lovers, siblings, best friends and neighbors. And when these perfectly nice characters behave in ways that shock us, we shudder with self-recognition that leads to insight—and then relief. Munro’s stories show that we are all connected—even through our experiences of moral failure and isolation, which can lead to revelation and growth.

Psychological and physical violence, often enacted in domestic settings, are recurring features of Munro’s canon. The author examines both the pathology of patriarchal society, and the unpredictable ways that people, nature, and our best-made plans can cataclysmically erupt; reconfiguring the landscape of our lives before we can comprehend what has happened. In one story, “Wenlock Edge,” Munro intimately introduces readers to a sexual predator; and in another, “Child’s Play,” the memory of an incident of murderous bullying, among nice girls, torments and shapes the bullies for the rest of their lives.

In “Dimensions,” the opening story, when Munro pushes a character’s obsession with control over the edge, readers encounter major themes and techniques of this collection and in the author’s work as a whole. A father, Lloyd, murders his daughter and two sons in a vengeful rage against his wife, Doree. In Munro’s stories, constant tension exists between those who hold power—whether material or psychological—and those who need or want more of it; and when a less powerful character gains strength, she often pays a brutal price. Such is the fate of Doree, the protagonist.

Frequently in Munro’s stories, as in life, signs of trouble-to-come show up early, but protagonists deny them, or don’t act soon enough to avert disaster. Like Doree, they participate in bringing upon themselves the calamities that lead to their journeys toward self-discovery.

Doree, a 16-year-old high school student, is first befriended by Lloyd, a hospital “orderly”—Munro loves wordplay—during her visits to her ailing mother, whose condition is said to be “serious but not dangerous.” Lloyd is admired by patients for his jokiness and “authoritative” demeanor.

Although he is only slightly younger than Doree’s mother, he flatters the girl in the elevator, telling her that she is a “flower in the desert,” and steals a kiss. When Doree’s mother dies suddenly, she chooses to move in with Lloyd, rather than stay with any of her mother’s friends. No mention is made of her having friends her own age.

After she becomes pregnant at seventeen, they marry, and Lloyd moves her cross-country, isolating her in a rural location “they have picked from a name on the map: Mildmay.” By nineteen, Doree has three young children.

Doree’s circumstances recall the young Munro’s. When the author was entering adolescence and developing as a writer in the 1940’s, her mother developed Parkinson’s disease, and Munro became her caretaker. Her route out of her life in rural Wingham, Ontario, was a two-year scholarship to the University of Western Ontario, where she published her first story at nineteen in 1950. As her scholarship was expiring, in 1951, she married fellow student Jim Munro, and by twenty-six, she was the mother of two daughters, with another to follow. One of her babies died soon after birth, and a theme that runs through Munro’s stories is that of children in danger or getting lost or dying.

As a young mother and author, Munro lacked long stretches to write a novel, and so wrote stories. During an era when women were pressured to choose between family and career, and reportedly feeling vulnerable about her developing art, Munro was quiet, if not secretive, about her writing.

In “Dimensions,” Doree challenges Lloyd’s absolute control by slowly beginning to assert her opinions on domestic issues. Initially she acts secretly when she suspects her decisions will contradict Lloyd’s wishes. When her youngest son becomes colicky, she worries her breast milk may be the cause, and on the sly, she supplements breastfeeding with bottle-feeding. Soon the baby wants only the bottle, and when Lloyd finds out:

She told him that her milk had dried up, and she’d had to start supplementing. Lloyd squeezed one breast after the other with frantic determination and succeeded in getting a couple of drops of miserable-looking milk out. He called her a liar. They fought. He said that she was a whore like her mother.

Lloyd becomes increasingly domineering; he wants more children, and wants them home-schooled. Because Doree no longer becomes pregnant easily, he searches her dresser drawers for imagined birth-control pills. A woman, Maggie, who is also educating her children at home, lives nearby. She befriends Doree. Lloyd dislikes Maggie and suspects Doree complains to her of his cruelty.

“It got worse, gradually. No direct forbidding, but more criticism.”

The terror builds.

One dinnertime, a spat between Lloyd and Doree, about something seemingly trivial—a dented can of spaghetti—suddenly escalates. Doree bought the damaged can because it was on sale, and she was “pleased with her thriftiness. She … thought she (had done) something smart.”

But when Lloyd accuses her of choosing the can because she wishes to poison the family, she dares not reveal to him that she thinks herself clever. Their three children witness, from the doorway of another room, the ensuing argument. For the first time, Doree stands up to Lloyd. She tells him “not to be crazy,” then leaves the children in the house with him, and walks to Maggie’s home, where she spends the night. When she returns the next morning, she discovers that Lloyd has murdered their children.

The themes of mass murder, economic hardship, and the struggle for equality reflect Munro’s life and times. She was born in 1931, on the eve of the Second World War. Her parents ran a fox farm that failed to adequately support the family in rural Ontario, where she has lived much of her life. Later, Munro was in her forties in the 1970’s, during the second-wave feminist movement.

The author learned first-hand the cost of standing out in her community. Her need to write economically and secretly—to lead a double life—began in childhood. During her youth, the stern Protestant culture of her Scottish ancestors, which had bolstered Canadian pioneers against prairie hardships, still prevailed. “The good” was equated with “the useful.” Community members subordinated their individuality to the needs of the group, and “showing off”—especially for “frivolity,” like writing fiction—was ridiculed.

“Who do you think you are?” was a taunt used to slap those who dared to exhibit skill and ambition. As a student, Munro seemed different from her peers; “marked” by her academic gifts and talents. In her story “Who Do You Think You Are?” the protagonist is punished by her teacher for demonstrating her photographic memory.

In Too Much Happiness, as throughout Munro’s canon, characters struggle with paradoxical feelings about being “marked” or “chosen.” They ponder the gains and losses that accrue from straying from the norm. A character who seems “different” to those around her may be perceived as being charming, ludicrous, threatening, repulsive, or all of these at once, depending on the shifting points-of-view of the observers.

Munro uses Gothic imagery and themes throughout her canon, as in this volume. Monstrous or grotesque characters who can’t hide their uniqueness abound, and reveal as much about their communities, through the responses they inspire in those around them, as they do about themselves, as they adapt to their circumstances. Marked and unmarked characters become doppelgängers; everyone is revealed to be marked in some way.

Munro then probes the ways in which characters who have invested in the conventions of their community and have repressed their singularity—or are trying to—punish those who can’t or won’t, or appear to be exempted from following unwritten rules about “fitting in.” In “Face” a father rejects his newborn for being physically imperfect. In “Some Women,” two women who share frustration about their own limited opportunities, manipulate and scheme to wrest power and favor from a happily married, career woman. And—typically—Munro uses geographical imagery to build her psychological atmospheres. In “Deep-Holes,” a family picnics at a location called Osler Bluff, which becomes a metaphor for the dysfunctional relationships between the story’s husband and wife, and the parents and children. Munro tells us that “the entrance to the woods looked quite ordinary and unthreatening,” until Sally, the mother, noticed “deep chambers, really, some as big as a coffin, some much bigger than that, like rooms cut out of the rocks.”

In “Dimensions,” after Lloyd murders the children, the newspapers report he told police he killed them to “save them the misery” “of knowing that their mother had walked out on them … ” He is judged “criminally insane,” and unfit to stand trial, and is placed in a “secure institution ,where Doree initially visits him, even though he expresses no interest in her. She is obsessed with the fear that she is the guilty, “crazy” party; that Lloyd is correct in blaming her for the disaster.

The narration of “Dimensions” moves back and forth in time, mirroring Doree’s fractured psychological condition after discovering that two of her children have been suffocated and one has been strangled to death by her husband. For the reader as well as for Doree, waking and dream states merge as Munro forces us to submit to and participate in the story, not analyze it, but allow it to wash over us, and penetrate our unconscious minds. The narrative layering deepens our understanding of Doree, and complicates her story, while creating a compression that enables Munro to conjure a novel’s worth of incident and character change. Using techniques like this throughout her canon, Munro has changed our understanding of what can be achieved in the short story, as in this volume’s “Fiction,” where the constantly changing viewpoints makes the story’s “truth” shift shape in ways like the experience of walking through a fun house of distorting mirrors. We stumble out at the story’s end, marveling at the beguiling relationship between fiction and reality; asking ourselves, “What is real?”

After the murders in “Dimensions,” Doree must take three buses to visit Lloyd; it is during one such journey that the story opens. She free associates, looking at words on bus advertisements and street signs, reorganizing the letters to make smaller words. The ordinary signposts of her life have lost all recognizable meaning for her. It seems she needs to invent a new language capacious enough to find words for the horror she has experienced—or perhaps a language narrower than the one everyone else is speaking—to allow her to block out everything but the struggle to emerge from her waking nightmare.

Munro’s characters often cling to daily rituals that offer the illusion of a predictable universe. Doree continues to get dressed each morning, and although a year and a half after the incident she has “not bought herself a single new piece of clothing,” she takes comfort in putting on a uniform for her tedious job cleaning rooms at the Blue Spruce Inn, because it “occupie(s) her thoughts to a certain extent and tire(s) her out so that she (can) sleep at night.”

Her desperation to reconnect with her children seems to be her primary reason to continue visiting Lloyd. She asks herself, “Who but (he) would remember the children’s names now, or the color of their eyes (?)” In a vivid dream, she reenacts, or rewrites, the story of the murders to create a more bearable outcome; she discovers that her children are all right—that “they were all playing a joke.” The workings of memory; the questions of how and why we continually revise the stories of our lives; the archetype of the story teller; and the process of writing—all are Munrovian themes. In Too Much Happiness, “Wood” also examines the workings of the creative process, as the protagonist discovers the benefits, risks, and price of pursuing his solitary passion for wood cutting.

In “Dimensions,” Doree edits and alters her telling of events depending upon her audience. Her method of survival has been to tell people whatever she thought would please them, or would protect others, including Lloyd, her abuser. Having interpreted reality from everyone’s viewpoint but her own, her repression has contributed to the death of her children, and her own psychological crippling.

As she gains strength with therapy, and less frequently visits Lloyd, he begins to compliment her looks, and then to write her letters in which he claims to be communicating with their dead children. The possibility that they still exist in what Lloyd calls their “Dimension” provides Doree’s first sensation, since their deaths, of “light(ness),” if not “happiness.”

In his letters, Lloyd frames himself as a victim, monstrously cast out from society. Doree, paradoxically, continues to fear she is monstrously guilty, even as she empathizes with Lloyd’s “isolation.” Her shock and trauma alienate her from the outside world and her more objective sense of self, jolting her out of her normal behavior patterns. In her new “reality,” in which the familiar seems strange, she moves from the house she inhabited with Lloyd, alters her appearance, and calls herself by her second name—Fleur—which in a foreign language recalls her first kiss with him. In a sense she wanders homeless, nameless, and friendless in search of connection with her dead children; she is a multigänger of them, of Lloyd, who created this sense of estrangement in her, and of her own previous self.

At last, Doree discovers the connection to her dead children that she needs in order to survive, by trusting in herself once again, and following the impulse of her nurturing nature.

Near the conclusion, a sudden, random incident occurs—synchronicity is vital to Munro’s stories. An underage male driver crashes his truck in front of the bus Doree is taking to visit Lloyd. The victim is catapulted out of the truck and lands, “arms and legs flung out,” like an “angel,” on the gravel. The bus driver stops abruptly, and Doree follows him into the road toward the victim. God-like, but selflessly—the inverse of Lloyd—Doree gives the wounded boy mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, breathing life into this other seemingly nameless person, who can respond to what she has to offer. She knows how to administer this technique because ironically “Lloyd … had told her, in case one of the children had an accident and he wasn’t there.”

In saving another mother’s child, Doree begins to heal the child within herself; begins to formulate her answer to “Who do you think you are?” She thereby experiences her own regeneration and finds her voice and sense of worth. When another motorist stops to help, the bus driver prepares to leave. Doree continues to revive the injured boy—who, like Doree, has played a naïve part in his own misfortune.

She tells the bus driver to leave without her. Like so many Munrovian heroines, she has been scarred by experience, but not destroyed. In the end, she achieves a moment of authentic human connection—of transcendent happiness—with a stranger. She can now move ahead into the uncertain future, and Munro narrates the rest of “Dimensions” in one unbroken, forward-moving stretch of time.

Alice Munro’s courageous writing has inspired controversy. In 1976, in Peterborough, Ontario, her coming-of-age novel, Lives of Girls and Women, was banned for “moral” reasons. When other authors’ works were similarly attacked in local high schools in 1978, Munro spoke out in her hometown of Clinton, Ontario:

Writers do have responsibilities—all serious writers make a continual, and painful, and developing effort, to get as close as they can to what they see as reality – the shifting complex reality of human experience. A serious writer is always doing that, not attempting to please people, or flatter them, or offend them … (M)oral books … deal with the question of how to live—what makes life not only bearable but what makes it honourable, how can people care for each other, how can we deal with hypocrisy and self-deception, how can we grow and learn and survive?

Munro offers us hints regarding her own approach to the question of “how to live,” in this collection. Her ideas challenge popular assumptions about what people will need in order to survive in our binary, “information age.” In the title story, Munro champions combining imagination with rational thought to help us work through problems. This calls to mind both the philosophy of William Wordsworth—a Romantic poet whom Munro has revered since girlhood—and a recent New York Times article that examined how the US military is studying how soldiers use intuition to detect hidden explosives in war zones.

In “Free Radicals,” Nita, the protagonist, thinks to herself: “She hated to hear the word ‘escape’ used about fiction. She might have argued, not just playfully, that it was real life that was the escape.” Indeed, Nita’s storytelling skill saves her life when she is threatened at home by a malignant intruder. As always, in Too Much Happiness, Munro seems to suggest that reading fiction and telling stories is essential to our efforts to cope with the complexities and dangers of existence.

Bibliography:

Benedict Carey, “In Battle, Hunches Prove to Be Valuable,” The New York Times, July 27, 2009.

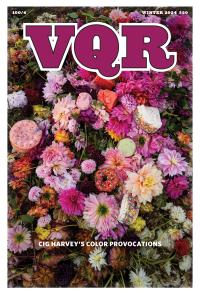

Lisa Dickler Awano, “An Interview with Alice Munro”, Virginia Quarterly Review, Summer 2006 and Winter 2010.

Lisa Dickler Awano Compiler and Editor, “Appreciations of Alice Munro,” Virginia Quarterly Review, Summer 2006, p. 91-107. Awano’s interviews with Margaret Atwood, Russell Banks, Virginia Barber, Ann Close, Douglas Gibson, Michael Cunningham, Charles McGrath, Daniel Menaker, Walter James Miller, and Pamela Wallin, presented as first-person essays.

Alice Munro, Too Much Happiness, Knopf, 2009.

Sheila Munro, Lives of Mothers and Daughters: Growing Up with Alice Munro, A Douglas Gibson Book, McClelland and Stewart, 2001.

Robert Thacker, Alice Munro: Writing Her Lives: A Biography, Douglas Gibson Books

2005.

Bio for Lisa Dickler Awano:

“Appreciations of Alice Munro,” Awano’s VQR tribute to Alice Munro, appeared in the Summer 2006 issue, and featured Awano’s interviews with certain of Munro’s peers, among them Margaret Atwood, Russell Banks, Michael Cunningham, and others, presented as first-person essays. Awano’s first VQR interview with Alice Munro appeared in 2006. Awano has previously profiled Alice Munro for the Vancouver Sun, and has been interviewed about Munro’s work on national and local radio programs. Other work by Awano has aired nationally on public radio in segments of Morning Edition and All Things Considered, and appeared in such publications as the New York Quarterly and Chicago Review. Awano is Head of the Office of Intercultural Outreach at the National Arts Club in New York City.