The Beginning of the End for Native Americans

As part of the general tumult for social and economic justice that accompanied the late 1960s anti-war movement (which I covered, in part, earlier), there was heightened interest and awareness in the genocidal march of history that decimated the native peoples of the Western Hemisphere and specifically the United States. Popular culture was infiltrated by Dee Brown’s Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee and the American Indian Movement’s stand at Pine Ridge in 1973 (for which AIM leader Leonard Peletier is still imprisoned). Shown for seventy-one days on the nightly news, it made the plight of Native Americans part of the progressive agenda. Hollywood even made a feel-good movie about the First Peoples, Dances with Wolves.

Here’s some of the recent (and not so recent) literature on the birth of this nation, which marked the real beginning of the end for native civilizations.

Guyasuta and the Fall of Indian America by Brady J. Crytzer (Westholme Publishing): Guyasuta, born in 1724, was a sachem of the powerful Iroquois Confederacy, and present at many of the major events of the revolutionary period. According to Crytzer’s vivid account, Guyasuta foresaw the demise of his peoples. He died a disillusioned alcoholic near Pittsburgh in 1794.

Dark and Bloody Ground: The American Revolution Along the Southern Frontier by Richard D. Blackmon (Westholme Publishing): Guyasuta’s story takes place in the northern and eastern American colonies; Dark and Bloody Ground covers Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia—and traces the conflicts between the Cherokee, Creeks, and Shawnee tribes and the relentless encroachments of the white settlers. The Cherokee attacked the then-illegal settlements in 1776, to which settlers responded with a scorched-earth strategy, thus making it possible for Kentuckian Daniel Boone, who has become an American folk hero, and others, to found settlements west of the Appalachians.

38 Nooses: Lincoln, Little Crow, and the Beginning of the Frontier’s End by Scott W. Berg (Pantheon): Here’s the story an ambitious film director ought to take up. A six-week insurrection fomented by Lakota in August 1962 was crushed, and a military commission found 300 warriors guilty of murder, sentencing them to be hung. President Lincoln pardoned all but thirty-eight, and that now stands as the largest government-sanctioned execution in American history. Berg’s account includes some memorable characters, including Little Crow, who was against the uprising but stood with his people: “[Little Crow] is not a coward: he will die with you.”

Rising Up from Indian Country: The Battle of Fort Dearborn and the Birth of Chicago by Ann Durkin Keating (University Of Chicago Press): Historian Keating takes up the previously ignored history of the Potawatomi tribe’s dealings with settlers, and rigorously examines the period between the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, in which the Indians gave away the future site of Chicago, and the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, which was a huge land swap. Keating also points out that early Chicago was a cross-cultural haven among the French, the Americans, and the Native Americans.

Dragoons in Apacheland: Conquest and Resistance in Southern New Mexico, 1846-1861 by William S. Kiser (University of Oklahoma Press): Having recently stolen New Mexico from Mexico, the US Army was quick to establish a presence with the elite mounted troops of First and Second United States Dragoons. William Kiser uses first-hand accounts to present the conflicts between the US and the various Apache (Mescalero, Mimbres, and Mogollon) tribes, and exposes the use of unauthorized tactics of total warfare. This is, of course, the beginning of a long struggle that continued until the defeat of Indian heroes such as Geronimo and Cochise.

Geronimo by Robert M. Utley (Yale University Press): One of a handful of Apache whose name has stuck in the popular culture (as a kind of ridiculous war cry), Geronimo was one of the fiercest of the fierce tribes known collectively as the Apache. This slim bio by a keen historian of the American West is a useful and illuminating picture of a complex warrior against the context of apocalyptic times for native tribes. Utley also wrote Sitting Bull: The Life and Times of an American Patriot (Holt), a historically accurate and vivid picture of the great warrior chief.

From Cochise to Geronimo by Edwin R. Sweeney (University of Oklahoma Press): This history focuses on the stormy period when the US continued to renege on past promises and ruthlessly drove the Apache to the San Carlos Reservation. Victorio and Geronimo refused and led warriors south into the Sierra Madre of Mexico, from which they tormented the US Army until Geronimo’s surrender in 1886.

Columns of Vengeance: Soldiers, Sioux, and the Punitive Expeditions, 1863-1864 by Paul N. Beck and Robert M. Utley (University of Oklahoma Press): This is a rigorous and detailed account of the Dakota War of 1862—the background for Berg’s 38 Nooses. Beck presents a picture of the conflict by accessing the letters, diaries, and personal accounts of the common soldiers as well as rare and previously ignored personal narratives from the Dakotas. Beck and Utley also point out that while the expeditions were viewed as punishment against those Dakotas who had started the war in 1862, the majority of the Sioux that the Army encountered had little or nothing to do with the earlier uprising in Minnesota.

The Wrath of Cochise: The Bascom Affair and the Origins of the Apache Wars by Terry Mort (Pegasus): Sparked by the kidnapping of the twelve-year-old son of Arizona rancher John Ward, the US Army lured alleged (with no proof) kidnapper Cochise to a meeting and then took Cochise’s family hostage. Cochise’s escape ignited a frontier war that raged for more than two decades—even beyond Cochise’s surrender. It’s a piece of history that contains all the ingredients of great drama—heroes and villains, and a noble culture decimated by greed and aggression.

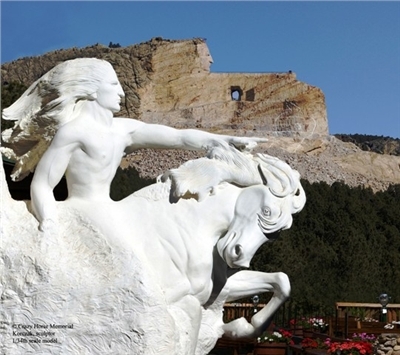

Crazy Horse by Larry McMurtry (Atlas Books). McMurtry writes:

Crazy Horse, a Sioux warrior dead more than one hundred and twenty years, buried no one knows where, is rising again over Pa Sapa, the Black Hills of South Dakota, holy to the Sioux. Today, as in life, his horse is with him. Fifty years of effort on the part of the sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski and his wife and children have just begun to nudge the man and his horse out of what was once Thunderhead Mountain. In the half-century that the Ziolkowski family has worked, millions of tons of rock have been moved, as they attempt to create what will be the world’s largest sculpture; but the man that is emerging from stone and dirt is as yet only a suggestion, a shape, which those who journey to Custer, South Dakota, to see must complete in their own imaginations.

This short book is an attempt to look back across more than one hundred and twenty years at the life and death of the Sioux warrior Crazy Horse, the man who is coming out of a mountain in the Black Hills, the American Sphinx, the loner who has inspired the largest sculpture on planet Earth. It will be an attempt to answer George Hyde’s pointed question: What was it all about?

Custer by Larry McMurtry (Simon & Schuster): In the hands of another writer, I don’t think another biography of George Armstrong Custer would warrant much attention, but Larry McMurtry’s rendering is a thoughtful account that compares the Battle of the Little Bighorn to the 9/11 attacks of 2001, “in that the whole nation felt it.” And he makes keeper of the flame Libby Custer a vivid character in her lifelong campaign to sustain Custer’s hero stature.

Though American popular culture has been neither kind nor accurate in portraying the First Peoples, there have been some outstanding exceptions. Australian director Bruce Bereford’s 1991 film of Brian Moore’s novel Black Robe was a wonderfully dramatic movie of Jesuit encroachment on native American life. It was highly regarded for its meticulously faithful recreation of indigenous lives. Also, Walter Hill’s film about Apache leader Geronimo (with Wes Stuckey as the great Chiricauha leader) is a cinematic treat, with a bravura performance by Robert Duvall as a frontier scout. Little Big Man with its comedic revision of western hagiography does provide a refreshing view of the Lakota, through charismatic charms of Chief Dan George. And Thunderheart (with Val Kilmer, Sam Shepard, Graham Greene and poet John Trudell) presents harrowing pictures of reservation life in the roiling 1970s.

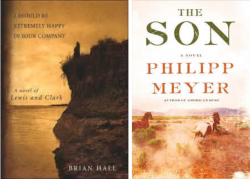

I’ve read two works of fiction that I felt were resonant with the day-to-day lives and point of view of Native Americans. Brian Hall’s I Should Be Extremely Happy to Be in Your Company: A Novel of Lewis and Clark (Pantheon) has Sacagawea, their guide, speaking—but of course not in English, a language she does not know. And Philipp Meyer’s The Son (Ecco), because one of the characters has been kidnapped, has a large section depicting Comanche life and culture.

It is worth noting that General Philip Sheridan, who prosecuted the Indian Wars, called an Indian reservation “a worthless piece of land surrounded by scoundrels.” Curious then, that despite a general acknowledgment that native peoples have been dealt with badly, conditions for many (the rise of casinos notwithstanding) continue to be deplorable. And deplore them is pretty much all that is done. What would have to change to help Native Americans out of the depredations of poverty, domestic abuse, high unemployment, and lack of education?

———

About the author: Robert Birnbaum’s Social Security number ends in 2247. He lives in zip code 02465 and area code 617. He was born in the 2nd month of a year in the 20th century. He doesn’t social network (used as a verb) except through his Cuban retriever Beny (named after Beny More, the Frank Sinatra of Cuba). Izzy Birnbaum also has cloud storage and uses electronic mail. He hopes his son Cuba is the second coming of Pudge Rodriguez. He mutters to himself at Our Man In Boston.