The Choice and Challenge of Being a Writer-Parent

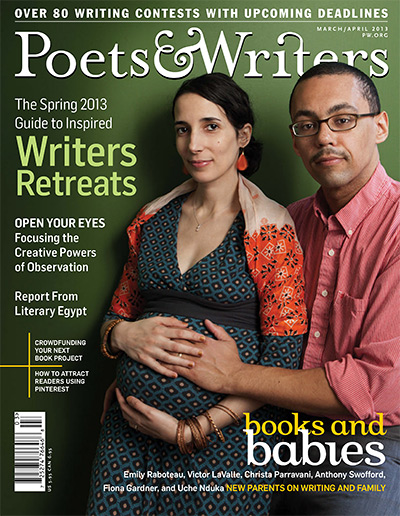

Poets & Writers (March/April 2013)

A recent issue of Poets & Writers features the married writing couple Victor LaValle and Emily Raboteau. “Books and Babies,” the magazine says on the cover. How do writers balance it all?

The article focuses on six writers: Raboteau, LaValle, Christa Parravani, Anthony Swofford, Fiona Gardner, and Uche Nduka. While each of these writers offer valuable insights about how their lives have changed since becoming parents, what the article fails to address are the practical concerns these writers face. In the six pages dedicated to the topic of “Books and Babies,” only one reference is made to “teaching schedules.” But this could mean many things. Are they adjuncts? Do they have tenure? Do all of them teach or do some of them stay home with their kids? Do some write full-time? Do they sell their plasma? Though the article repeatedly refers to “the demands of being an artist,” the specific nature of these demands is never named or explained.

The article further neglects any discussion of daycare, babysitters, housekeepers, nannies, family support, help from neighbors or any of the other (often expensive) networks on which working parents have come to depend. While some attention is paid to the imbalance of demands placed upon female writers over male writers, just what those demands are and how these writers resolved them—by relying on family for help, by typing while breastfeeding?—remains unstated. We learn simply that these writers mustered energy and found that being “stuck in the house for the rest of the evening” helped to facilitate writing work.

Rather than explore the financial challenges to being a writer-parent (and thus opening up a conversation about these concerns), the article focuses exclusively on the nonmaterial. We learn about these writers’ feelings (“complicated”), their spousal dynamic (“supportive partner with similar values”), the effect of parenthood on one’s writing (“motherhood changes one’s writing” and “made their writing better”), and concerns over the prospect of their children reading their work (“anxious”).

How can we talk about “life with babies” if we don’t talk about the economic dimensions of the experience? When interviewing writers about this topic, I found that it is in fact not the disruption to writing time that worries writers the most. Rather, adding more financial demands to lives already defined by financial instability was a pressing factor. Many writers I spoke to would be unable to afford childcare.

“My partner and I live a modest but comfortable life,” says 29-year-old Laura Van den Berg, author of What the World Will Look Like When All the Water Leaves Us. “We would need a lot more money to raise a child. What feels like a windfall for us now would go toward covering bare necessities if we had a child.”

D., a 34-year-old writer based in San Antonio, Texas, told me, “I work 6 days a week to pay my bills and survive. I have almost no income left over, little to no time for housework … I try to carve out 30 minutes to an hour of [writing] time a day, but I know a child would monopolize the little time or money I currently have.”

“Writing,” says Cathy Elcik, a 37-year-old writer in Boston, “is done in what most other people call their leisure time. My vacations are usually built around writing. I look forward to days off where the hours stretch out writing.” Elcik, who is deeply conflicted about whether or not to have children, says, “When you’re a writer, there’s the wage job and then you go home and the writing competes with family life. What wins in that battle for hours?”

Writers who give talks, do readings, and attend conferences may feel additional uneasiness at the prospect of a child at home. Van den Berg, who cobbles together a salary from multiple gigs, says that having children would require that she “curtail traveling—which is, when traveling for paid events, an important part of my income.”

Lack of financial resources invariably leads to less time available for writing. For many, the prospect of putting writing aside, even temporarily, leads to a real fear over personal well-being. Yael Goldstein-Love, 35, author of The Passion of Tasha Darksy, says, “I’ve never managed to go more than a week without working on some piece of fiction. I’m unmoored when I don’t have a fictional world taking shape inside of me.” Similarly, Elcik told me, “When I’m not writing … the depression that is always at the edge of my mind gets storm clouds.” D. echoed the sentiment: “When I don’t write I feel like a stranger in my own body … Rarely writing would undoubtedly make me suicidal or homicidal. I’m not saying this for comedic effect either. I have a medical history of anxiety and depression.”

The Poets & Writers article is not unique. When it comes to articles about balancing writing with kids, it’s tough to find frank discussion about money and time. On writer Cari Luna’s blog, Luna invited 22 parent-writers to discuss their experiences. Geraldine Brooks says, “My writing job starts when the school bus arrives. I watch from the kitchen window as it pulls away and pour a fresh cup of coffee. On the way to my study, I pick up the Norton Anthology of Poetry. I let it fall open at random and read whatever poem I find. Then, pump primed by those buffed and honed words, I sit down to work.”

Whether Brooks is supporting herself and her family through her many books, articles, teaching, or all of the above is not clear.

Other writer-parents do make reference to financial circumstance, yet their experiences are often discussed in terms of luck. Sophie Littlefield says, “When my children were twelve and fourteen I made the decision to write full-time. I was lucky in that I had been a stay-at-home parent and our household was supported by my husband’s salary.”

Jane Smiley says, “I should stress that I was living first in Iowa City and then in Ames, Iowa. Ames was a uniquely great place to write and have kids, because Iowa State had a great child development program, and the daycare in town was very up to date and wonderful … I was lucky to live in Ames.”

This emphasis on luck, or atypical circumstance, seems to imply that for the average writer hoping to balance income-earning work with writing and parenting, only one solution is available: be lucky.

In her introduction to the series, Luna raises the question, “How to balance writing the novels with editing other people’s books for money?” It’s a great question. But she quickly dismisses the issue by saying, “That’s a different story.”

On the contrary, for the majority of writers who have kids or are thinking about having kids, balancing paying work with writing work while also raising a child is the entire story.

Because the conversation about having children is often framed in terms of values and attitudes as opposed to economic conditions, many writers I have spoken to feel that the decision not to have children makes them appear selfish, self-absorbed, overly ambitious, or cold-hearted.

Thirty-year-old Kelly Davio, author of Burn This House and editor of The Los Angeles Review, asked me, “Is it wrong not to invest energy in a child? Does it make me a bad person?” Similarly 48-year-old J. of British Columbia, who says that she’s felt that her “lifestyle was not very suitable to having kids” told me, “I guess in a way it is being selfish for my own goals in life.” And 37-year-old Ilan Mochari, author of Zinsky the Obscure, who feels that he would “be much more open to becoming a parent if I had disposable income and the time it creates” referred to his “next long handwritten draft” as “self-absorbed” in comparison to starting a family.

Yet all of the writers I talked to, far from being selfish, have thought quite seriously about a potential child’s best interests. For many, writing time is not just a means to getting ahead in one’s career or to publish, but a necessity on par with food and shelter. All of the writers I spoke to worry about the quality of childcare they could provide, knowing full well that children are needing and deserving of such care.

When articles about being a writer-parent do not address financial dimensions of this experience, many writers wind up feeling quite alone in the decision-making process. D., whose undergraduate and graduate school debt totals $88,000, told me, “If a publisher gave me $500,000 to publish my manuscript, I would likely get pregnant in the next two years. That amount of money would allow me to pay off my school debt, not have to work full time, and provide me with more writing time … Until I answered [your] questions, I wasn’t aware the extent to which my choices were situation-based.”

Elcik said she feels the pressure of “a choice against a person you’ve never met [versus] an art that’s fed your soul through the balance of the shittiest lows in your life…When you sacrifice a child at the altar of your book, there’s a pressure for it to be fucking phenomenal. Oprah and Elizabeth Gilbert can decide not to have kids, fine, but who the fuck are you with your story that three people will read.”

Goldstein-Love also remains unsure—and her mother, who is also a novelist, worries for her. “She thinks it would be a big mistake for me not to have children, given how much I want them.” Goldstein-Love, who grew up watching her mother “turn out gorgeous novel after gorgeous novel” never thought she would have to decide between writing and motherhood. Yet she says, “If I had financial stability—either through my own work or my partner’s—I’d have had children years ago. I’m 35 and neither my partner nor I make enough money to support a child, and I’m not sure when we will. My partner knows how much I want a child, and he supports me in that desire in the sense of saying that, yeah, when we have some more money we can try to have kids.”

Naturally, not all child-free writers have agonized over the decision. Van den Berg has expressed no desire to have children. Davio told me, “I’ve always had a very clear vision for what I want from my life: a loving partner, the time to write, and fulfilling work.”

Of course, there is no one right answer for everyone. Each writer must make the writing life—with or without kids—viable in his or her own way. Still, any conversation about balancing parenthood with writing ought to include the specific circumstances of writers’ lives.

——

About the author: Becky Tuch is the founding editor of The Review Review and a founding member of the literary blog Beyond the Margins. Her fiction has received fellowships from The MacDowell Colony, The Somerville Arts Council and awards from Briar Cliff Review, Byline Magazine and was listed in Wigleaf’s Top 50 Very Short Stories of 2013. Other stories have appeared in Hobart, Eclipse, Folio, Night Train, Quarter After Eight, and elsewhere. In 2011 and 2012, The Review Review was named “Best of the Best” among Writer’s Digest’s 101 Best Websites for Writers. She teaches at Grub Street in Boston.