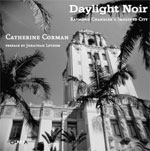

Daylight Noir: Raymond Chandler’s Imagined City

Catherine Corman’s Daylight Noir: Raymond Chandler’s Imagined City—a book of Corman’s photographs paired with passages from Chandler’s work—is more an interpretive lens than an attempt to define a city. Like a camera that can only see in infrared, Corman has attuned her sensibility to view only what lies within the Chandlerian spectrum.

Chandler’s work remains as interesting as ever: his depictions of a corrupt Los Angeles peopled with hardboiled detectives, damaged starlets, compromised DAs, and lonely diner patrons straight out of Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks are fine tableaus of their time. And his stories are still popular in 2009 because, like the films they directly inspired or can claim kinship to (Chinatown, L.A. Confidential, etc.), they entertain, even if his use of then-popular vernacular like “coppers” now seems dated. But that seems to be what’s wrong with using new photographs to bring Chandler’s work into the modern age: Philip Marlowe is an appealing, lasting archetype of the hardboiled private eye, but the people he met and places he skulked through no longer match the physical reality of contemporary Los Angeles. For good and bad, we (I am an L.A. native and current resident) are no longer a city of street cars, vintage movie houses, undeveloped hills, deeply corrupt cops, and yellow journalism, although TMZ has laid claim to whatever remains of the latter. The city is also far more multi-ethnic than it was in Chandler’s era—although Filipinos and Latinos do appear in many of his stories—and wealth and power have shifted definitively from Dowtown to the West. Sure, our problems are no less spectacular—drought, fires, earthquakes, gangs. But with violent crime the lowest it has been since (funnily enough) Chandler’s era, L.A.’s issues often veer towards melodrama or the prosaic: an epidemic of burst water mains; a mayor who seems too engaged in world travel and dating newscasters to solve our traffic and public transport issues; the burgeoning soap opera of the divorce of the Dodger owners Frank and Jamie McCourt; a large budget deficit; debates over how to handle coyotes in Griffith Park.

All of this is to say that there’s something strangely anachronistic about trying to summon, as Corman does, visions of Chandler in present-day L.A. Occasionally, there are Chandlerian echoes, even a bona fide flashback, like the Anthony Pellicano case. Ours is still an imperfect town, with some blighted places, like Skid Row, and imperfect institutions, the LAPD included. But to try to evoke something noirish or hardboiled in daytime photographs of various city structures fails to match up. So few buildings and places are the same as in Chandler’s work—his descriptions of Westwood Village that Corman invokes are unrecognizable—that his books function better as dark shards of folk history, rather than maps.

That disconnect may explain why many of Corman’s photographs are taken at close or oblique angles, often at positions that allow buildings to tower over the camera, as if forcing themselves into close association with the Chandler-passages juxtaposed alongside. Many of the photographs are beautiful, particularly her shots of City Hall, one of which is on the book’s cover, but some are also abbreviated, haphazard things—an amorphous bit of ornamentation on a building’s facade, or some rotten wood-shingled roofs made to represent the “Mendy Mendedez’ Club” (sic). “Watch your lip, Mendy Mendedez don’t argue with guys. He tells them,” the text says, and it’s a reminder of what’s missing in these photographs: the people. Not even a pigeon appears in these photos, much less a person. Some palm trees and airplanes are the only hints of life. That’s why, after piecing through this book and finding myself more drawn to Chandler’s words than anything else, I want to go back to his work and the movies they became. Better to see his vision fully drawn, the people, traumas, and places he so ably described—not mythologized.