Is Free Verse Killing Poetry?

Editor’s note: After VQR’s Spring 2012 issue released, I received an e-mail response to Willard Spiegelman’s essay, “Has Poetry Changed?” from former National Geographic photojournalist and published poet William Childress. I asked him to elaborate further on that commentary, to which he sent the following.

–––

When Willard Spiegelman, noted scholar, critic, and editor of Southwest Review, wrote a penetrating essay in the Spring 2012 Virginia Quarterly Review, “Has Poetry Changed?”, I wanted to reply, “Not fast enough to suit me!” However, the change I wanted was to step back a century and start re-assessing rhymed and metrical poetry.

Free verse has now ruled the poetry roost for ten decades, and its record for memorable poetry is spotty. Catching on around 1912 when Harriet Monroe was starting Poetry, the apparent writing ease of vers libre attracted millions of poetasters, not to mention the support of Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, and other important poets. No more struggling to find le mot juste, or create original images. Just sit down and write.

As you may have guessed, I’m a formalist, but I’ve written and published a lot of free verse—mainly because of editorial bias against form poetry. In the hands of the right poet, which is true of any form, vers libre can shine—but we’ve had a steady diet of it for way too long. We are, unofficially at least, a one-poetry nation, and various editors, publishers and hidden agenda-ites seem determined to keep us there. As David Orr points out in Beautiful and Pointless: A Guide to Modern Poetry, “There is complete avoidance and disdain for the kinds of poetry pre-Baby Boomers were raised on.”

Well, I’m a pre-Baby Boomer, and I think such favoritism is stupid, petty, and demeaning to poetry. Form poetry is the kind of poetry a third of living Americans grew up with. A nation that discards its traditions and history is a nation without pride in itself. When I was a youth in the 1940s, most poetry was gentler and more pleasant in tone, but powerful in effect. As a migrant worker and the son of a sharecropper, my schooling was sporadic and interrupted. But somewhere I came across a poem by John Crowe Ransom, “Bells for John Whiteside’s Daughter.” The way he used words to paint pictures was so powerful, it was like a stonecutter engraving them in my memory.

The lazy geese, like a snow cloud,

Dripping their snow on the green grass,

tricking and stopping, sleepy and proud,

Who cried in goose, Alas …

A few years after reading the lyrical beauty of a poem that could make me feel good, even about death, came Howl, Allen Ginsberg’s nihilistic free verse oral diarrhea—and suddenly the world was supposedly singing the praises of Ginsberg’s drug-poisoned pals, who

let themselves be fucked in the ass

by saintly motorcyclists

and screamed with joy

who blew and were blown by those human seraphims, the sailors

Howlin’ Allen has the right to describe the rotting sowbelly of life, but I have the right to say it’s pointless, and as far from real poetry as shit is from Chanel #5. Beat poetry went far toward making ordinary Americans see poets as drug-crazed society-wreckers who wrote only for themselves. By definition, that makes them elitists.

I researched a large stack of Beat poetry magazines from the 1970s and 1980s for this post, ranging from Doug Blazek’s Olé Anthology to Kumquat 3 and E.V. Griffith’s highly touted Hearse (“A Vehicle for Conveying the Dead”). Not only were 95 percent of the poems free verse, many of them hewed to a core of societal destruction that in another era would sound like fascism. It was an argument for too much freedom encouraging anarchy. Vitriol was plentiful, but ways to improve things were not.

A blind person can see that American society is in turmoil, with a fractured government and enormous debt. Both political parties are to blame—but shouldn’t poets be trying to change things instead of writing chaos-poetry or “woe is me” diaries? Who will read poetry when they can’t find a common bond in a poet’s writing? Who likes ruptured grammar, twisted syntax and what my grandpa called flapdoodle? There’s at least a partial consensus that free verse these days consists of a lot of badwriting. I forget who said, “Poets should learn to write before they try to write poetry.” Many of today’s poets don’t seem to realize that all writing is connected.

Here’s another example of free verse:

Clench-Watch:

Fear-spores in-coil taut

(and calm) as copper-snakes

or-springs—before they cause.

From the sweeping grandeur of The Iliad and The Odyssey to this unfinished fragment in less than 3,000 years. God bless progress. This techie poem is tighter than post-Preparation-H hemorrhoids, but is it poetry, or what we called, back in the day, doodling? It was written by a pleasant-faced young man named Atsuro Riley, and is being hailed as a breakthrough for free verse. Breakthrough to what? This is the amazing shrinking poem. Soon we’ll be gone. Can modern poets be poeticidal?

I agreed with Spiegelman in several areas. Like him, I don’t read much modern poetry. Of today’s writing students he said, not unkindly, “Only a small percentage can satisfy the technical prosodic demands and also write a syntactically accurate English sentence.” And they want to be poets? Free verse must be sending students a message that form poetry does not: beginning poets don’t need “syntactically accurate sentences” to write free verse.

At 80, I won’t spend time trying to fathom the Rubik’s Cube verse of Atsuro Riley, although I wish him well. His poetry just doesn’t move me, and movements are important to octogenarians. I’d rather read Lewis Carroll than Atsuro Riley.

Beware the Jabberwock, my son,

The jaws that bite, the claws that snatch,

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious bandersnatch!

***

In 2006 John Barr, head of the Poetry Foundation, wrote: “American poetry is ready for something new, because our poets have been writing in the same way for a long time now. There is fatigue and stagnation about the poetry being written today.”

Who determines what’s poetry and what’s not? Who are the grand taste-makers? I have always heard, and understood, that poetry has no definition—an argument that goes back to at least the 17th century. If true, how is it that critics, reviewers, and bureaucracies can give awards, prizes, and accolades to certain poets and poetry? How do they define the best of an indefinable art? And why do the rest of us sheep go along with it?

How about something old, Mr. Barr, instead of something new? Really good poems, like wine, improve with age. But free versers have welded shut the doors to the past. Where once we recited favorite poems (always rhymed), or had them taught in school, we now ignore the orphan art in droves. We’re trying everything but free coupons, and the results are a combination circus (slam poetry) and coldly mechanical poems that verify the nature of our earplug-wearing, neighborless, push-button society. Where are the sabot throwers when we need them?

Poet Dana Gioia wrote in his 1992 essay “Can Poetry Matter?”:

American poetry now belongs to a subculture. No longer part of the mainstream of artistic and intellectual life, it has become the specialized occupation of a relatively small and isolated group. Little of the frenetic activity it generates ever reaches outside that closed group. Like priests in a town of agnostics they still command a certain residual prestige. But as individual artists, they are almost invisible.

Not only a telling comment 20 years ago, but an accurate prophecy of our current malaise. Poets should also be aware of a report from the University of Florida at Gainesville, which followed MFA graduates for a decade. Only ten percent landed writing or editing jobs. The rest found jobs in real estate, insurance, or McDonald’s. Memphis State University’s Thomas Russell wrote, “Ninety percent of the MFA students are never going to publish a word after they leave the program.”

Poetry needs readers, not writers, but how many poets read any poetry but their own? As one editor said, “All poets should stop writing for a year.” When I was studying poetry in Philip Levine’s class in 1962, he made a point of telling us, “Poetry is the most useless art.”

Yet poetry has been discovered by commerce. The dean of American verse magazines, Poetry, turned 100 in 2012, and is trying to avert a poetryless future. In 2003, it received a $200 million dollar bequest from Ruth Lilly, and has become a kind of Sears Roebuck for poets and readers. That’s fine with me. I grew up with Sears Roebuck, and not just in our outhouse. Christian Wiman’s inking of all kinds of poetry means there’s now something for everyone. The fact that Wiman’s editorship has increased Poetry’s readers from 11,000 to 30,000 is a hopeful sign. He also says poets should be well-grounded in form poetry before leaping into vers libre. Even that ol’ fascist Ezra Pound announced: “Poetry should be at least as well-written as prose.”

When Germaine Greer declared, “Art is anything an artist calls art,” she probably didn’t mean Thomas Kinkade, who painted for more plebian tastes and died very rich. The gulf between what is and is not art has been debated forever—the blind leading the blind into a kind of elitism. If no definition exists, why are critics, reviewers and the American Academy of Poets tripping over each other to laud the hottest vers libre poet in years? Perhaps I’m unkind—but everyone else is so laudatory, I felt that at least one ordinary mortal should challenge the gods.

What goals do modern poets have? At least during the Viet Nam War, poets wrote antiwar poems and marched. I was among the 225,000 anti-Viet Nam War marchers in 1969, when Nixon watched football in a White House surrounded by a protective ring of buses. A former student of mine, Danae Walczak, contacted me not long ago to remember that march. Why have there been no major demonstrations against Afghanistan, when our government can’t even say why we’re there? As a Korean War veteran in the Washington march, my goal was to get our guys home. In August 2012, a young marine, murdered by one of our “Afghan allies” did come home—in a casket. The turnout for his funeral was enormous, with hundreds lining highways and bridges. How many poets will be concerned enough to write poems? Or will they be too busy entering contests and seeking easy recognition?

I’m not advocating control of vers libre, which has been around since the Book of Kings,just that its adherents stop stifling rhyme and meter poems. If poetry is to survive, it needs to use everything in its armory, especially metrical rhymed poems—serious, humorous, nonsensical, satirical, even insult poems. Variety, as Christian Wyman found, is the spice of life, and it’s absurd to think that vers libre should be the only form American poetry should take. No wonder John Barr found stagnation in American poetry. So loosen up, vers librists, and ask formalists to join you. Poetry needs all the help it can get. Or can’t you write good rhymed and metrical poems? Walt Whitman couldn’t.

—

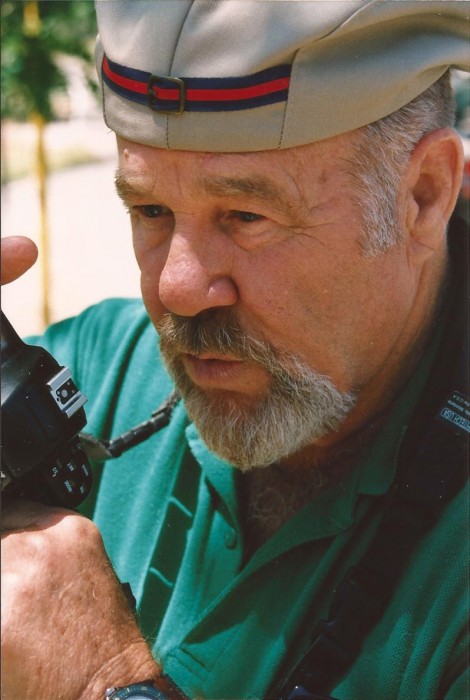

About William Childress

Fifty years ago, William Childress published his first antiwar poems in Poetry. Then he spent decades as a freelance photojournalist. A former National Geographic editor/writer, 2011 saw his poems published in Steel Toe Review, CT Review, and the Connecticut Review. An environmentalist, his “Flight of the Wild Goose” will appear in Bird Watcher’s Digest this October. His 14-year column in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch was twice nominated for the Pulitzer Prize. In August 2012 he was awarded the $100 second prize in The National Senior Poet competition.