A Gun and a Girl: The Case for Hard Case Crime

Any scan of the bestseller lists shows a national book culture awash in pulp. But all those hungry zombies, vengeful angels, vampire lovers, scrappy postapocalyptic teens, and fairy princess-warriors with wicked blades and toned physiques bear little resemblance to pulp fiction as once defined. For one, the current breed’s mash-up of action, steam-heated eroticism, and the fight for agency is specifically target-marketed for female readers. Earlier phases of the pulp-fiction industry—in actuality heavy with women-oriented melodramas—are remembered now for their male-dominated output. As understood today, pulp fiction began with the nineteenth century’s hyperbolically violent “blood and thunder” westerns and continued through the men’s crime and adventure stories of the pre-World War II era.

But when you say the words “pulp fiction,” those who don’t immediately flash on the Quentin Tarantino film will think of a style popularized in the postwar era. This is the sort of thing that a scrappy outfit like Hard Case Crime has been trying to rejuvenate, despite all popular trends to the contrary (it being an accepted publishing truism that men don’t read). Launched in 2004 by novelists Charles Ardai and Max Phillips, Hard Case’s mission statement announces their dedication to “reviving the vigor and excitement, the suspense and thrills … of the golden age of paperback crime novels.”

The pulp fiction of that time was closer in design to Jean-Luc Godard’s formulation about all that’s needed to make a movie: “A gun and a girl.” This is the Mickey Spillane model, in which lunk-headed avengers like Mike Hammer punch their way to justice like George Patton assaulting northern France. Fists like rocks, an appreciation for the dames, a well-oiled .45, and a suspicion of all that ironic James M. Cain and Raymond Chandler patter (very prewar).

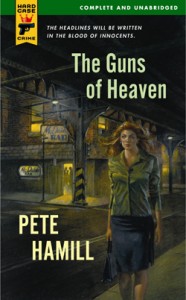

Fortunately, Hard Case has gotten out of the Mike Hammer rut, even though it features an admiring quote from Spillane himself right on its website’s splash page. It is one of the only imprints out there with a genre mission as well as a dedication to branding—that snappy logo with the snub-nosed automatic and a crown (because it’s the king of pulp?) on a bright yellow background—low price points, and gorgeous painted cover art that evokes the melodramatic covers that now fetch a high price on the collector’s market.

Its list is heavy with the likes of Max Allan Collins and Lawrence Block, the former being something of a professional nostalgia factory, and the latter a crackerjack noirist who can knock out opening lines like that of Grifter’s Game with seemingly little effort: “The lobby was air-conditioned and the rug was the kind you sink down into and disappear in without leaving a trace.” A 1961 novel (rereleased by Hard Case in 2004) that feels of its time without any painted-on period detail, it’s about a mean-spirited twist of a scammer who lucks into discovering a pile of raw heroin when checking into an Atlantic City hotel. Pretty soon he’s discovered the owner and is plotting some financially rewarding murder with the man’s wife, a hot-to-trot number who doesn’t mind lovemaking on the beach or leading men to their doom.

Newer on the Hard Case list is a series of eight novels churned out by Michael Crichton under the pen name John Lange while he was attending Harvard Medical School in the late 1960s and early-70s. Hacked computers, terrorists, evil corporations doing shady bioengineering, and shipwrecks: These books cover the gamut of popular airport fiction. The African treasure hunt Easy Go, first published in 1968, feels at first like a dry run for Crichton’s later Congo. Shamelessly drawing on the old thrill of haunted-pyramid potboilers, Crichton assembles one of those only-in-fiction teams (morality-free journalist, conflictedarchaeologist, gadfly millionaire with a succession of nubile girlfriends) in the Egyptian desert to dig for an undiscovered tomb whose contents they want to spirit out of the country without Cairo knowing. Anachronisms aside (over usage of “Negro” and some outrageous sexism), it’s an initially easy read that quickly bogs down with a lack of direction surprising for a writer whose later output was many things but almost never dull.

But still, Hard Case hasn’t relegated itself to one kind of writing. That much is apparent in three of its latest releases.

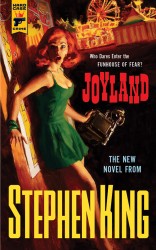

Stephen King helped Hard Case get much of its early publicity back in 2005, when it published his throwback crime novel The Colorado Kid. King’s second book with the press is Joyland. The setup is almost more Judy Blume than Spillane. Naïve college kid Devin Jones is a self-described “twenty-one-year-old virgin with literary aspirations” stuck in a miserably unreciprocated love story: “The heartbreaker was Wendy Keegan, and she didn’t deserve me.” Finally kicked to the curb, Jones heads south to work at a North Carolina amusement park for a summer. Needless to say, he learns about much more than how to heal his broken heart.

But with its easygoing mood and lack of interest in ginning up much of a plot machine, Joyland more recalls those sparkling, thoughtful novellas King occasionally releases during those between-novel interregnums. As usual with King, there is little moral ambiguity here. We know from the start that our narrator is a Good Guy, and over the summer he discovers numerous ways to make that known, from excelling at dancing inside a giant dog outfit to the delight of children to helping out a beautiful woman with a crippled son. By the time King gets up a murder mystery, it seems almost beside the point amidst the book’s summertime revel, which is glorious like a faded old favorite T-shirt.

More clearly dedicated to Hard Case’s mission statement, though not in a guns-and-dames way, is Harlan Ellison’s Web of the City. Originally published as Rumble in 1958, it has the squalling jazzy oomph of the era’s best livewire troubled-teen stories. Ellison’s hero is Rusty Santoro, the one-time boss of Brooklyn street gang The Cougars. He made the mistake of stepping back from leadership and so gets stomped by the rest of the gang. After that, things spiral down fast, from beatings and gang fights to bloody murder and bloodier revenge. It’s the kind of story where Rusty reacts to a man’s advances by burying a fork in the offending hand.

Ellison has said that he did research for the novel (and a series of stores) by going undercover in a Brooklyn gang in his early twenties. But where the novel really sings is not the fact-checked details of 1950s youth gang life, but the fervid emotion that pulses off each page. Even in his best work, Ellison has had a weakness for purple prose, and that’s definitely the case here. But lines like “the gutters had claimed their own” and mythological characters like The Beast (whose eyes “were filled with a great void, a great sadness, a great uncaring, unknowing sadness”) make perfect sense issuing from the mind of an overheated, doomed-by-circumstances adolescent like Rusty. While the plotting couldn’t be more compact and crowded, it’s difficult to imagine a book like this issuing forth from today’s pulp authors. There is too much literary striving here, too much pop-operatic sincerity for the vampire-hunter crowd.

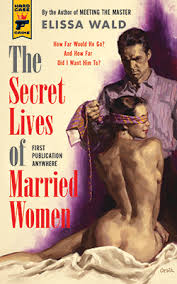

While the first half feels too wispy to cohere, the second has more heft to it. Leda’s sister Lillian is an unhappily married defense attorney who becomes interested in a blind client’s impeccably servile young female assistant. Not much happens here, but Wald — who achieved some renown for the 1998 collection of sadomasochistic fiction Meeting the Master and is only the second woman to have written a book for Hard Case — does an excellent job of limning the assistant’s heartbreaking need to be wanted and to serve: “Somewhere within the dream of slavery is the dream of adoption: of being taken off the auction block, taken home.” Her writing has a crisp efficiency to it that can lead at times to a toneless hum. Try as it might, the book can’t quite break out in terms of boundary-pushing taboo exploration or criminal melodrama.

Hard Case best fulfills its mission statement in books like these last three, where the idea of pulp fiction isn’t constrained to a predetermined style but rather an insistence on vivid stories and punchy writing, nearly regardless of what they’re about. That’s pulp.

——

About the author: Chris Barsanti opinionates for Publishers Weekly, The Barnes & Noble Review, and other fine publications both terrestrial and cyberspacial. He is the author of Filmology and the Eyes Wide Open film guide series. You can visit his website at chrisbarsanti.net.