Homeland: A Series on Terra Firma

The following post by Becky Tuch is part of our online companion to our Winter 2013 issue on Classic Hollywood. Click here for an overview of the issue.

———

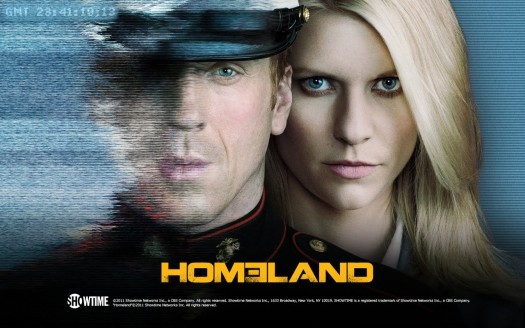

Much has been made of the TV series Homeland, which wrapped up its second season on Showtime in December of last year. “Groundbreaking,” critics have called it. “Revolutionary.” “It’s an ace thriller,” writes Scott Collura for IGN TV, “keeping the viewer on the edge of their seat … while it also has something to say about the seemingly never-ending War on Terror.” In an interview with Radio Free Europe, actor Navid Negahban observed, “No one has ever seen anything like this on U.S. television.”

There’s no question that this show delivers thrills and moments of “nail-biting” suspense. Actors Claire Danes and Damian Lewis deserve every Emmy possible for their roles as CIA agent Carrie Mathison and US Marine turned Al-Qaeda operative Nicholas Brody. Nevertheless, the series is not such a radical departure from countless dramas American audiences have seen again and again, its central paradigm regurgitated in sitcoms and soap operas, horror movies, mafia capers, and zombie flicks. While the characters may differ and the settings may change, the underlying narrative remains constant: alien powers threaten to subvert American values and, in particular, values of a privileged middle and upper classes.

Take for instance the idea of the home, a repeated motif throughout Homeland. When Carrie surveils Brody at the beginning of the series, she watches him, in his house, from her house. Carrie and Brody’s love affair takes place not in a hotel or an office, but in Carrie’s family cabin. Nearly all of Brody’s interactions with his wife, Jessica, take place in their house. As subversives, Aileen Morgan and her husband Raqim Faisel recognize the importance of assimilating into American culture. Thus the first time they appear on-screen, they are closing on their new home. When Brody is to be interviewed by a television news station, great care is made in arranging the furniture and paintings of his home. Even Abu Nazir, the man responsible for “turning” Brody, lives in a nice house. In fact, it is in that home that Brody becomes a tutor for Nazir’s son and bonds deeply with the boy.

Beyond pointing to the socioeconomic status of the show’s protagonists, the home motif provides a way to see the show as a drama of bourgeois experience. Brody and Jess may argue in their living room or Carrie may spy on Brody in his bathroom, yet the characters’ problems remain on a purely psychological realm. Houses in Homeland are not things to fret over, with a concomitant slew of financial pressures and endless chores. Rather houses are spaces for the characters to occupy, offering safety, security, and comfort.

Contrast this view of the home with a show like The Wire, and you’ll see stark differences. Here, much of the drama between protagonists occurs outside the home—on street corners, in courtrooms, prisons, bars, or inside workspaces. Even when the young drug dealers are “home,” there is little private space as many of the rooms are shared with family members. The courtyard of the projects serves as a collective home base, where people can hang out and where social dramas unfold. In the ghetto, writer/activist Sister Souljah has observed, private space does not exist.

While Homeland might be said to be about the experience of “home,” one would be mistaken in thinking this a universal experience. Rather, it is a uniquely upper-class experience of private property and private space.

Unfortunately, the show’s director has failed to see any distinction in this regard. In explaining to the Charlotte Observer why so many scenes were shot in North Carolina, Michael Cuesta observed, “It really captures the mainstream suburban America look, which is perfect for our series because it’s called ‘Homeland’ and it’s about the threat to that.”

What would it take for a show like Homeland to be truly provocative, legitimately groundbreaking? Perhaps clarifying the terrorists’ positions would be a start. Writers Laila Al-Arian and Joseph Massad have both commented on the implausibility of the show’s stated alliance between Al Qaeda and Hezbollah. Indeed, by the end of Homeland’ssecond season, what has a viewer learned about the history of Hezbollah, a Lebanon-based militant group? Or the different goals of Shiite-led Hezbollah and Sunni-led Al Qaeda? What about American imperialism? Does Abu Nazir, the show’s “terrorist mastermind” ever once express a view on the American support of dictatorships in Egypt and Turkmenistan? Does he offer an opinion on American military aid to monarchies in Saudi Arabia and Jordan? Do any of the show’s terrorists ever articulate what they’re fighting for or what ideologies they oppose? As Rachel Shabi in the Guardian has observed, “Abu Nazir was bad long before his son’s death and we don’t know why.”

In their book Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman discuss the five “filters” through which news media need to pass in order to bypass censorship. One of these is anti-communism such that no news broadcaster may ever express a view that is pro-communist and anti-capitalist. In recent years, critics have replaced “communism” with “terrorism,” claiming that no media outlet may ever express a view that presents the positions of terrorists as legitimate or rational.

Of course, giving voice to what these terrorists actually want, think, and believe may risk alienating viewers. But what about the Muslim perspective? Why does Brody pray in the morning? Why does he face the garage door when he prays? Why does he wash his hands or buy a special rug? That these are rituals of Islam may be clear, but the history and meaning of these rituals is never explicated. Nor is Brody’s faith. He claims he converted to Islam because the religion offered him comfort during his time as a POW. Why? What aspects of the religion might offer solace? Homeland not only denies that terrorists are driven by anything other than familial bonds and vague anti-imperialism sentiments, but it also never allows any of its characters to articulate ideas about Islam—apart from incorrect and intolerant ones. Thus just as white, middle-class experience is taken as a given, the viewer is never encouraged to think of Islam as a coherent system of beliefs on par with those that define Judeo-Christian identity.

Homeland is not unusual. In fact, the show’s popularity may be partly attributed to its utterly familiar narrative devices. While the story may be “edge of the seat” suspenseful, viewers are ultimately on terra firma in the affirmation of bourgeois fantasy. The comfort of the home (as characterized by home ownership in the suburbs) and the value of the nuclear family (as depicted by two children and a docile stay-at-home mom) are never fundamentally questioned. On the contrary, such values are cemented into the viewer’s psyche as immutable, wholly natural ways of being.

From the zombie movie to the alien-invader flick, from the daytime soap opera to the spy thriller, from Mad Men to Breaking Bad to The Simpsons to I Love Lucy, viewers are asked to repeatedly indulge in a “What if?” game wherein cherished norms are threatened, but only for awhile. In the end, the nuclear family will be healed, perhaps made stronger. The home will be restored, perhaps made better. And often, as in the case of Homeland, the perceived virtues of whiteness, property ownership, and Christian faith will be exposed to risk, but will ultimately prevail. They are, after all, the only virtues given a credible point of view.

———

About the author: Becky Tuch is the founding editor of The Review Review, a website dedicated to reviews of literary magazines and interviews with journal editors. She has received fellowships from The MacDowell Colony and The Somerville Arts Council and awards from Briar Cliff Review, Byline Magazine, and elsewhere. Her fiction has been short-listed for a Pushcart Prize and Glimmer Train’s Very Short Fiction Award and has appeared in Hobart, Folio, Quarter After Eight,and elsewhere.