Hothouse in the Hot Seat

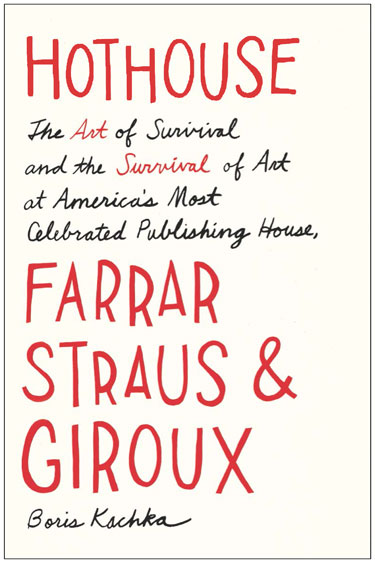

Boris Kachka has covered the trade-publishing beat for more than thirteen years at New York Magazine, and one could look at his forthcoming book Hothouse, which Simon & Schuster will publish August 6, as a rite of passage akin to a Bar Mitzvah. The advance attention from booksellers and publishing types for the book, a history of Farrar, Straus & Giroux and the two figures, Roger Straus and Robert Giroux, who loomed largest over the publishing house’s six decades, has been almost uniformly rapturous, garnering the number-one slot for August’s Indie Next list.

But Hothouse’s predicament begins with its declaration near the beginning that to best understand Straus and Giroux as men and as book publishers, “it pays to begin at the end, with their memorials, each a perfectly tuned tribute to an inimitable man.” Kachka established his fixation on publishing’s apparent death with his September 2008 piece naturally titled “The End.” (Spoiler: It wasn’t.) Beginning at the end likely saves time in providing an overview of FSG’s key figures and showing the contrast between Straus’s outsized personality and Giroux’s self-effacement, but it also plants the question that dogs Hothouse throughout: How will it reach regular readers who have no idea what FSG is, and aren’t inclined to care?

To his credit, Kachka gamely wrestles with this problem. Once past the obligatory, desultory personal-origin stories—Giroux’s Catholic stock versus Straus’s Germanic Jewish, department-store-earned family money—he moves briskly into the creation of FSG itself, quickly dispensing with John Farrar (already in physical and mental decline by the early 1950s) to concentrate on the contrasting personalities of the book’s dual subjects. Giroux emerges with his dignity intact, his attention focused more on editing his authors or lamenting books that got away (like Jack Kerouac’s On the Road). Straus, on the other hand, is revealed in all his awful glory: standing firm on penurious author contracts and cursing out agents who dared to challenge his despotism; belittling his son and presumed heir Roger Straus III, who eventually leaves FSG for more commercial houses; and presiding over the “sexual sewer” that FSG would become in the sixties and seventies: “If Roger used sex to cement loyalty, he could also wield raunch as a weapon.”

Gossip about the goings-on at the office or of authors like Philip Roth, Isaac Bashevis Singer, and Carlos Fuentes burst forth from the pages of Hothouse. And if you’re a woman, be it an upset Joan Didion when Straus forces her to stay at FSG after her longtime editor leaves, or Straus’s stalwart secretary and alleged sometime-lover Peggy Miller, you really didn’t have it so good within the FSG bubble. Miller, in fact, is another problem point in the book, as Kachka values other former employees’ hearsay over Miller’s own attempts to keep her self-respect on the nature of her relationship with Straus. The effect is that she comes off as pathetic, when keeping tabs on the often-shaky finances of FSG required a Herculean effort—and is something to be celebrated.

As for the publishing house’s financial history, Kachka diligently catalogs the changes FSG experienced. There’s the bath Straus took on publishing President Harry Truman and the boon of its first acquisition—Creative Age Press—with the money made from FSG’s first big hit, Look Younger, Live Longer. There are the long-term contracts given to authors who don’t produce (Tom Wolfe delivered Bonfire of the Vanities almost twenty years late) and the near-insolvency in the early 1980s, byproducts of Straus’s determination to stay independent (until he finally sold to von Holtzbrinck in 1994); the move into the dingy, heat-challenged Union Square offices and then over to more normal digs just a few blocks away on 18th Street. The FSG of Straus’s heyday might have blanched at the Times Square billboard ad for The Marriage Plot, but only briefly, before being secretly delighted.

The most compelling figure in Hothouse is Henry Robbins, a hotshot editor so revered by his authors (Didion’s 1990 collection After Henry is named for and dedicated to him) that it made Straus apoplectic when Robbins decamped to Simon & Schuster. Kachka describes that failed mentor relationship in a way that captures interest, but, for scope purposes, leaves out one of Robbins’s most intriguing accomplishments—publishing Nine and Half Weeks by Elizabeth McNeill as editor-in-chief of Dutton—just a year before his sudden death of a heart attack outside a city subway station in 1979.

But if the end is the beginning, then Hothouse’s end, which ought to supply some grander meaning for the exercise, does not. Despite faithful research, dozens of interviews, and a strong desire to jump through the looking glass of time to inhabit the world he wrote about, Kachka can’t make the case for why FSG matters outside of the book trade. Sure, the house published important authors, and working there would have been a cauldron of inappropriate comments and behavior, but that doesn’t extrapolate to the wider post-war world in the same way as the television show Mad Men, which Simon & Schuster touts as a comp. Roger Straus isn’t Roger Sterling. Peggy Miller isn’t Peggy Olson. And Robert Giroux certainly is no Don Draper.

The very qualities that make FSG the force of prestige it is paradoxically demonstrate the publisher’s larger weaknesses. As is already clear, those in the book trade will enjoy reading up on a supposedly glamorous past (and, in some instances, look for their own or their colleague’s name and hope for the best or worst, whatever their preference) but not necessarily find what’s exceptional or fresh about the subject or the house. A history of Ballantine or Fawcett Gold Medal would be clearly tied to a major transformative event in publishing and wider readership, the dawn of the paperback original and the creation of pulp fiction. A history of New Directions, a smaller, even more rarified publishing house, would be narrower and more tightly focused. To be a microcosm of America, a subject has to be all-encompassing and distinct. And FSG, at least as depicted in Hothouse, turns out to be a little too midlist.

———

Correction: An earlier version of this piece stated that Giroux was a WASP. That is incorrect; he was a Catholic.

Editor’s note: This piece first appeared at Publishers Marketplace.

About the author: Sarah Weinmanis News Editor of Publishers Marketplace and editor of Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives: Stories from the Trailblazers of Domestic Suspense, published by Penguin on August 27.