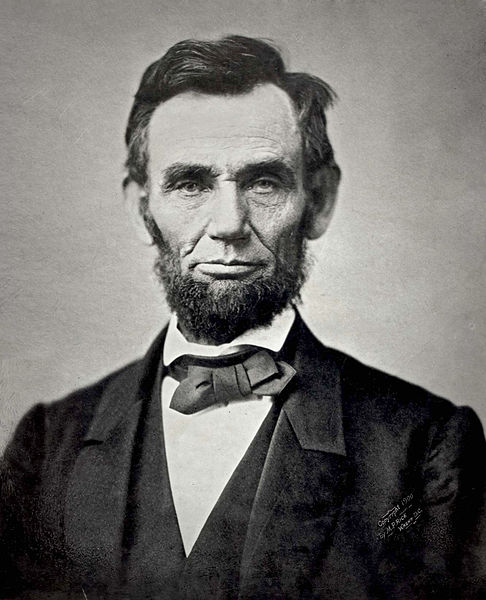

Lincolnania, or Everything You Wanted to Know (and Then Some) About Abraham Lincoln

People interested in the 16th President of the United States have not been short changed. Adam Gopnik, in his book Angels and Ages, observes that only the biographical literature of Jesus and Napoleon is larger than that of Abraham Lincoln. Thomas Frank’s exegesis (which I enthusiastically recommend) of Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln in February’s Harper’s Magazine asserts an estimated 16,000 (and growing) books have been written about Abraham Lincoln. There is a some joke in publishing circles that suggests if a writer is looking for a book to write, one on Lincoln’s dog (as far as I know, he didn’t have one) will get some editor’s attention.

One might suppose that Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln has heightened interest in both the publication and reading of Lincolnania. Of course, Bill O’Reilly has already written two novels that in some way relate to Lincoln, Killing Lincoln: The Shocking Assassination That Changed America Forever, with Martin Dugard, and Lincoln’s Last Days: The Shocking Assassination That Changed America Forever with Dwight Jon Zimmerman.

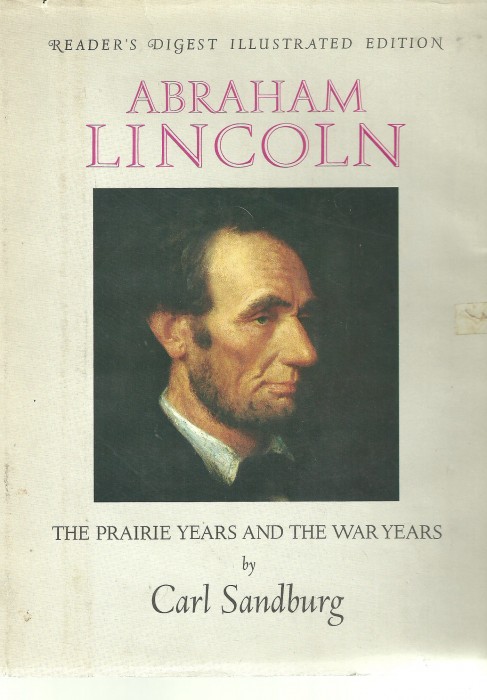

Of straightforward biographies, a few shelves might hold the all-purpose profiles. Carl Sandburg, the sage of the Prairies and extoller of the City with Strong Shoulders, has written six volumes, Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years & The War Years (though its antiquity may be incomprehensible to the current generation); David Herbert Donald’s Lincoln and James M. McPherson’s Abraham Lincoln are single volumes, contemporary, and serve well any general purpose. Personally, I am unabashed in admitting that my most vivid composite of Abraham Lincoln is Gore Vidal’s Lincoln. In fact, were I allowed to teach about the United States in the 19th century, I would rely heavily on Vidal’s five-novel Empire series as the basic texts.

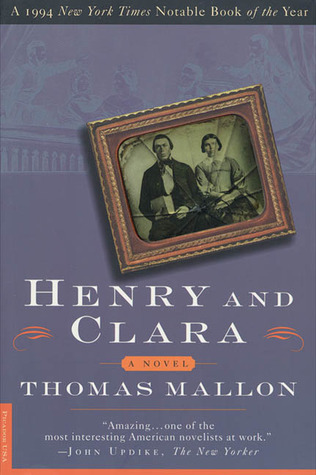

I cannot mention novels without heralding Thomas Mallon’s intense novel Henry and Clara, which tells the story of the young Union officer and his wife, who occupied the box adjacent to Abraham Lincoln at the Ford Theater on that fateful night. Mallon has departed on the best kind of flight of imagination and yet presents a fully vivid montage of the 19th century as it draws to a close.

Let me now and here say that if you have any expectations of a current bibliography of recently published Lincolnania that includes titles such as Lincoln: Vampire Slayer or Lincoln’s Grave Robbers, you have stumbled into a space that will be foreign to you (you are, of course, welcome to stay).

Per usual, there have been at least a half-dozen tomes shedding light through narrower windows of Lincoln’s life. The titles are self-explanatory:

• The Hour of Peril: The Secret Plot to Murder Lincoln Before the Civil War by Daniel Stashower

• Lincoln’s Code: The Laws of War in American History by John Fabian Witt

• Rise to Greatness: Abraham Lincoln and America’s Most Perilous Year by David Von Drehle

• Lincoln’s Hundred Days: The Emancipation Proclamation and the War for the Union by Louis P. Masur

• A Wicked War: Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. Invasion of Mexico by Amy S. Greenberg

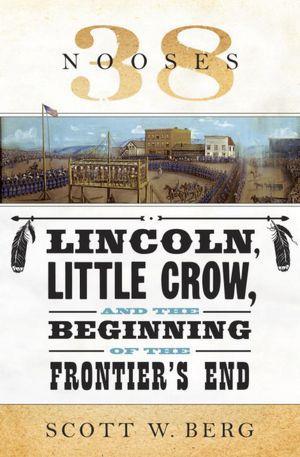

• 38 Nooses: Lincoln, Little Crow, and the Beginning of the Frontier’s End by Scott W. Berg

I find A Wicked War and 38 Nooses particularly interesting, as they are neither paeans to US exceptionalism or hagiographic tracts reaffirming Lincoln’s greatness. They are more about discomfiting history and less about the myth building that has fed the bottomless imperial maw. Amy Greenberg’s focus—the title is taken from Ulysses S. Grant’s characterization of that episode—is the mid-19th century US incursion into Mexico, known, unsurprisingly, as the US-Mexican War, a belligerence that is at least the equal of the scurrilous imperial adventure known as Operation Shock and Awe. Lincoln, on this occasion it appears, was on the right side of history.

And 38 Nooses retrieves the story of the Dakota War of 1862, which led to “largest legally sanctioned execution in American history.” Four inebriated Native Americans heedlessly murdered a small number of white settlers. Predictably, the US Army intervened and defeated Chief Little Crow’s Dakotas and then a military court sentenced 300 natives to be hung. Mercifully, President Lincoln reduced the number to 38.

Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln, published in 2005 and reportedly the ur-text for Tony Kushner’s Lincoln screenplay—and the then Senator Barack Obama’s favorite book—is ripe for a serious dissection and Thomas Frank provides one in his above mentioned Harper’s piece:

… Team of Rivals is uninspiring to the point of boredom. It is not only a retelling of the most familiar story in American history but also a fairly dreary one. Goodwin’s account doesn’t provoke or startle with insight. Most of what she tells us has been told us before—many, many times.

Frank employs the trademark searing wit and piquant humor that has made him a bestselling author (What’s Wrong With Kansas? and Pity the Poor Billionaire), and takes time out from his Goodwin vivisection to piss on Spielberg, calling Lincoln “not only a hackneyed film but a mendacious one … Spielberg & Co. have gone out of their way to vindicate political corruption.”

Frank concludes:

If you really want to explore compromise, corruption, and the ideology of money-in-politics, don’t stack the deck with aces of unquestionable goodness like the Thirteenth Amendment. Give us the real deal. Look the monster in the eyes. Make a movie about the Grant Administration, in which several of the same characters who figure in Lincoln played a role in the most corrupt era in American history. Or show us the people who pushed banking deregulation through in the compromise-worshipping Clinton years. And then, after ninety minutes of that, try to sell us on the merry japes of those lovable lobbyists—that’s a task for a real auteur.

Amen.

———

About the author: Robert Birnbaum is a monthly columnist for VQR. He was born in Bamberg, Germany, grew up in Chicago (from the Southside to the Northside), and has lived in Brookline, Massachusetts, and Exeter, New Hampshire. He is editor-at-large at IdentityTheory and something or other at The Morning News, and keeps a blog at Our Man in Boston. He lives with his Cuban Retriever, Beny, in West Newton, Massachusetts.