Making Sausages: Images of Governance

During recent snowbound days, I indulged in a bout of binging the second season of House of Cards, the celebrated political drama starring Kevin Spacey, Robin Wright, and a brilliantly cast supporting ensemble. Actually, I did the same binge with the first season’s thirteen episodes and apparently suffered no deleterious effects (except falling behind on some deadlines). This time watching the Shakespearean machinations of the Macbethian couple spawned some ideas, which you will find in what follows. But let me digress for a moment on the show.

In the opening episode of season one, we learn that Francis (Frank) Underwood/Spacey is a South Carolina congressman and majority whip, promised the Secretary of Stateship by the president he helped elect—a position he was promptly denied, as the president felt he would serve better in his legislative role. Spacey sabotages the president’s designee for Secretary of State and finagles his own choice into that position. Claire Underwood/Wright heads an NGO, and when we first meet her she has ordered her office manager to substantially downsize the staff. The trusted manager reluctantly complies and is the last one fired. The ubiquitous character actor Michael Kelly plays Doug Stamper, Underwood’s quite lethal bagman; Kate Mara as Zoe Barnes is an ambitious and relentless newspaper reporter. Reg E. Cathey plays Freddy Hayes, the proprietor of Underwood’s favorite rib joint. The accomplished Molly Parker joins the cast for the second season as Underwood’s handpicked successor as majority whip, Jackie Sharp.

It should not go unremarked that the US House of Cards is an adaptation of a 1990 BBC series based on Michael Dobbs’s novel of the same name. Having viewed the BBC version, I can offer that it rivals watching paint dry on my watchability scale.

My initial reaction to the first skein of installments was bemusement and an appreciation of the various components of this visual narrative—casting, montage, bumpers, editing, music, performance, and most of all the writing. But having devoted so much time to this entrancing narrative, I found it sparking a host of ideas about how governance has been portrayed in popular novels and films.

Films

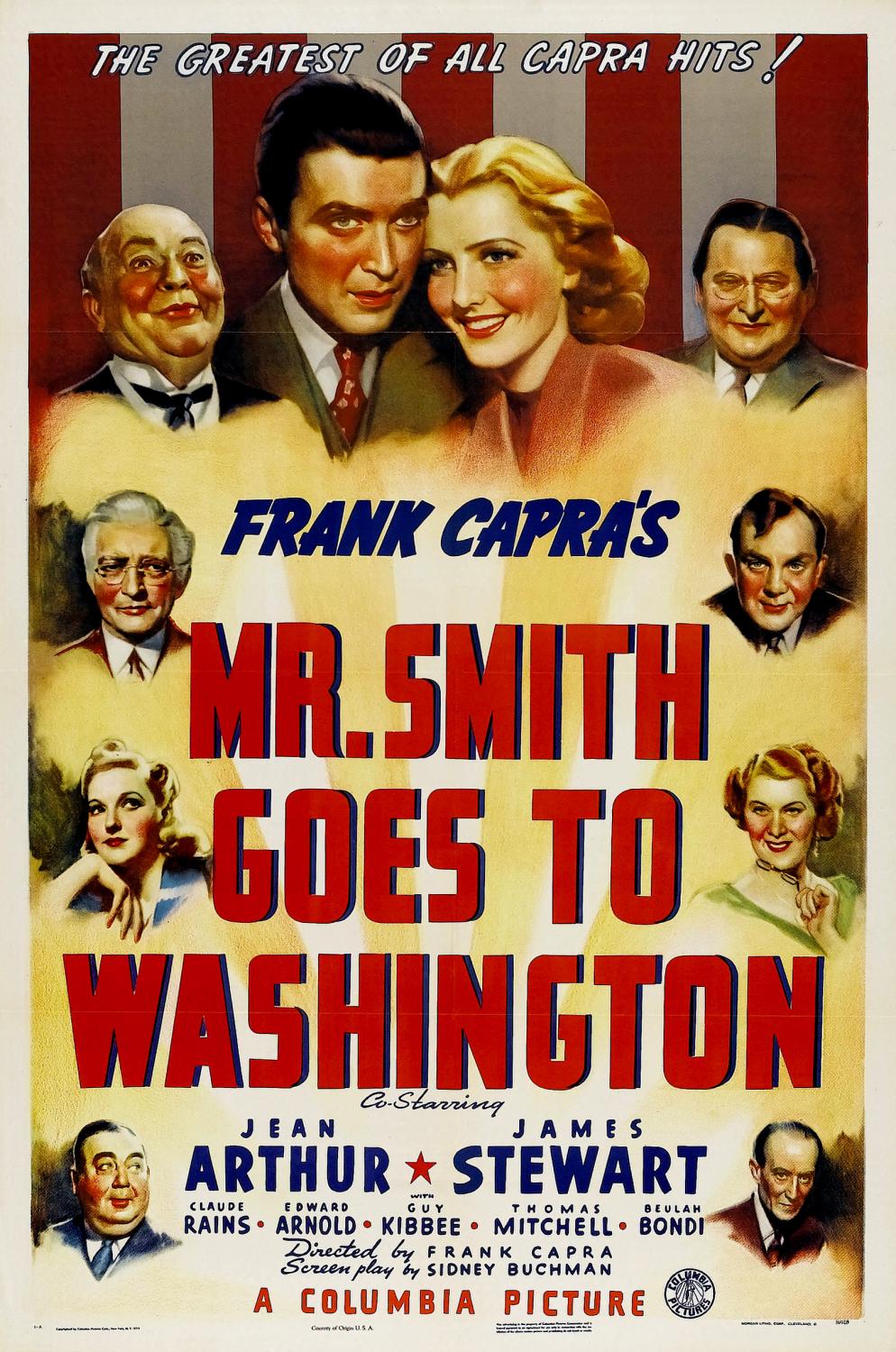

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington: Hollywood director Frank Capra’s classic features Jimmy Stewart as recently appointed Senator Jefferson Smith, who quickly learns what makes Washington work and stages a filibuster to gum up his state’s political boss’s agenda. Can you imagine a senator saying, as Senator Smith (in earnest) says, “I guess this is just another lost cause, Mr. Paine? All you people don’t know about lost causes. Mr. Paine does. He said once they were the only causes worth fighting for. And he fought for them once, for the only reason any man ever fights for them; because of just one plain simple rule: ‘Love thy neighbor.’… And you know that you fight for the lost causes harder than for any other. Yes, you even die for them.”

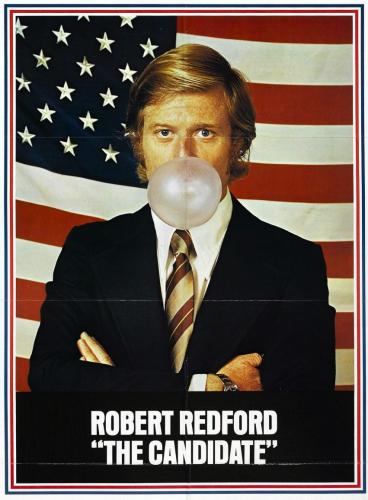

The Candidate: Robert Redford plays a California lawyer and political neophyte who is tapped to run in a senate campaign he won’t/can’t win. Except he does and delivers a bracing punchline/last line in this satire as Senator-elect McKay, musing on his unlikely victory: “What do we do now?” Written by novelist Jeremy Larmer (Drive He Said), a speechwriter for Senator Eugene J. McCarthy’s 1968 campaign for the presidential nomination, the film fell in between the raucous presidential campaigns of 1968 and 1972, and the revelations of Watergate. Reportedly, former Senator and Vice President Dan Quayle claimed the film inspired him.

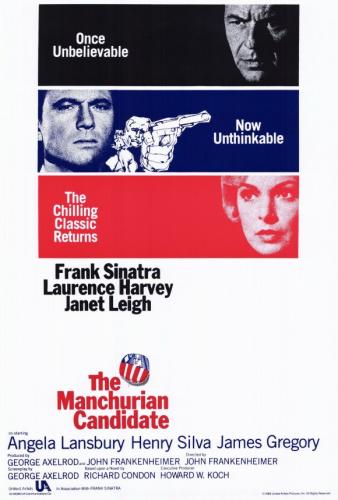

Seven Days in May, Doctor Strangelove, JFK, The Manchurian Candidate: These films illustrated fairly well what historian Richard Hofstader described in his seminal essay “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” which concludes, “We are all sufferers from history, but the paranoid is a double sufferer, since he is afflicted not only by the real world, with the rest of us, but by his fantasies as well.” For example, there was a claim that received inordinate attention that fluoridation of drinking water was a Soviet plot. Fletcher Knebel’s novel-turned-movie Seven Days in May posits a military coup of the federal government. Richard Condon’s The Manchurian Candidate proposes nine brainwashed assassins. In Terry Southern’s satire, Dr. Strangelove: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, adapted for film by Stanley Kubrick, a rogue Air Force officer, Gen. Jack D. Ripper, initiates a nuclear attack on the USSR, bypassing the Commander-in-Chief, the Pentagon, and Joint Chiefs of Staff. US President Merkin Muffley explains to the Soviet premier:

“Hello, Dimitri…. I’m fine…. Now then, you know how we’ve always talked about the possibility of something going wrong with the bomb…. The bomb, Dimitri. The hydrogen bomb…. Well, now, what happened is that, uh, one of our base commanders…he went a little funny in the head….and he went and did a silly thing….He ordered his planes to attack your country.”

Lincoln: No matter what your view of Steven Spielberg, a latter-day Frank Capra, and his hagiographical Lincoln (written by Tony Kushner and reportedly owing credit to Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals), his approach of focusing on Lincoln’s campaign to gain passage of the Thirteenth Amendment (outlawing slavery) was a graphic and useful exhibition of the reality of the legislative process—a process Otto Von Bismarck is given credit for alluding to in a famous aphorism, “There are two things you don’t want to see being made—sausage and legislation.” By the way, historian Alan Rosenthal debunked this metaphor in 2001, writing “that sausage making was cleaner, more efficient, more collaborative and better labeled.”

Books

Team of Rivals by Doris Kearns Goodwin (Simon & Schuster): Whatever their standing in academia, popular historians such as David McCullough, Stephen Ambrose, and Nathaniel Philbrick have, through their adoption of literary narrative styles, made the recounting of American history lively and vivid and thus accessible to nonhistorians. Goodwin, who has academic credentials (Harvard Ph.D.) and was a Lyndon B. Johnson White House staffer, has written biographies of several US Presidents, including Johnson (Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream). In Team of Rivals, her most ambitious and seemingly by consensus her most successful book, takes an unusual approach to what was at the time an unusual happenstance. Abraham Lincoln appointed to his cabinet his major political rivals, and Goodwin presents mini-biographies of each. Thomas Mallon, gifted novelist and sure-footed critic, keenly observes and credits Goodwin:

Having produced a paucity of personal letters and no diaries in an era when public men often composed a surfeit of both, Lincoln … forces biographers into a greater-than-usual reliance on what contemporaries wrote about him. Their diaries and letters become competing, fragmentary gospels through which the Union’s savior is reconstructed into a tentative whole. One sees this oblique method, the alternation of multiple perspectives, again and again in modern depictions of Lincoln.

Harlot’s Ghost by Norman Mailer (Random House): In 1991, when I finished Mailer’s arborcidal (1,328 pages) novel sitting on the beach at Rincon, Puerto Rico, I felt a measure of pride for my diligence in finishing this large, sloppy narrative. More than twenty years later, that pride has been amplified by the silly fact that I have never met another person who has read this oddity by Mailer. Its rambling and epoch-spanning narrative about the CIA and the conduct of American foreign policy drew me in because of its plausibility and verisimilitude—especially the schemes and intrigues that are set in post–World War II Berlin and Montevideo, Uruguay, where the protagonist ends up working with Howard Hunt (of Watergate infamy). Harlot’s Ghost was published at a time when public understanding of the machinations of the CIA were substantially different than today. Mailer was/is mostly fun to read even when he pontificates—though 1,300 pages of his metaphysics and less endearing tropes may be a bit much for the less dedicated.

Shelley’s Heart by Charles McCarry (Random House): First published in 1996, Shelley’s Heart by Charles McCarry, a former CIA operative and author of a well-regarded series of CIA-based novels, was prescient in presenting a narrative of a stolen presidential election and the constitutional crisis that follows. The title is taken from the story that Percy Shelley’s heart was extracted from his cremation and buried separately. In McCarry’s novel, the heart is the totemic emblem of a college secret society (The Shelleyans) formed at, where else, Yale. The novel opens with a liberal Democrat narrowly defeating a conservative Republican in the presidential election of 2000. Losing candidate Franklin Mallory uncovers computer tampering and voter fraud that tilted the election in three key states. Before the inauguration, he reveals his discovery to the incumbent President elect and asks for his resignation. Additionally, President Lockwood has been complicit in a plot to assassinate a terrorist Arab leader (an act frowned upon pre-2001). There is also a plot to install Archimedes Hammett, a radical lawyer, as Chief Justice and the heroic intervention of the alcoholic Speaker of the House to round out this complex political thriller. McCarry’s deft depiction of Senate hearings and cloakroom finagling illuminate the less visible processes of governance and are suggestive of the darker possibilities of how the constitutional order is being gamed.

Boss: Richard J. Daley of Chicago by Mike Royko (E. P. Dutton): Chicago, ”the city that works” except when it doesn’t, was blessed with a quintessential daily newspaper reporter named Mike Royko (apparently a role model for other city reporters such as defrocked suburbanite Mike Barnacle). In 1971, Royko gifted Chicagoans and the rest of the English-speaking world with an adroit profile of the leader of the last of the big-city political machines and the undisputed Mayor, Richard J. Daley. Now Daley is known nationally for his unseemly behavior during the feverish 1968 Democratic (Presidential-nominating) Convention and also for gifting John Kennedy enough votes to carry Cook County and thus Illinois and consequently the election. Royko’s exegesis of Daley’s life and road to unfettered power is leavened with his understated wit and eye for the ridiculous. This is a handbook for municipal executive function and highly instructive. Amusing, too.

Lincoln by Gore Vidal (Random House): I have long held that I have learned as much (possibly more) from historical novels by such craftsmen as Gore Vidal, Thomas Mallon, and Geraldine Brooks than the history texts that were foisted on me in various courses. Vidal’s work, which over the objections of his publisher he named “The Narratives of Empire” series (as opposed to “American Chronicles”), is a heptalogy of historical novels (Burr, Lincoln, 1876, Empire, Hollywood, Washington DC, and The Golden Age). His Lincoln is a model of keen observation and narrative skill that writers such as David McCullough and Goodwin strive. Expectedly, Vidal’s portrayal was attacked as was the miniseries based on it. Vidal wrote a “defense,” in which he concludes:

Nothing that Shakespeare ever invented was to equal Lincoln’s invention of himself and, in the process, us. What the Trojan War was to the Greeks, the Civil War is to us. What the wily Ulysses was to the Greeks, the wily Lincoln is to us. I am neither Homer nor Virgil. But it is of those arms that I have tried to sing, and of that man—not plaster saint but towering genius, our nation’s haunted and haunting re-creator.

You may find the defense in its entirety here.

The Best and the Brightest by David Halberstam (Random House): Pulitzer Prize–winning New York Times reporter David Halberstam’s agenda in his seminal study of the Kennedy coterie that exercised the reins of power was to ruminate on how a group of gifted minds tripped into the colossal blunder known as the Vietnam War. Though previously presidential staffs had been studied (mostly Roosevelt’s colorful Brain Trust), Halberstam’s skill exposed some crucial dysfunctions. Think of it as a kind of Moneyball of presidential staffing written with a literary bent.

All the President’s Men by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein (Simon & Schuster): Two Washington Post junior reporters did a prize-winning job of uncovering the web of corruption that spread out from the Nixon White House to the aptly named CREEP (the Committee to Reelect the President) to the Justice Department to the FBI. The biggest lesson of all was that the dirty tricks and moral lapses identified were not recent innovations, something of a shock to many citizens. Woodward and Bernstein adeptly made clear the erasure of the boundary between politics and governing and sadly a dysfunction that has not been mitigated since the Watergate era.

The rampant distrust of government and its functionaries has been a serious problem (hence the Tea Party, and even worse, local militias) in part because the transparency to which politicians give lip service is a false and inauthentic exercise, which contemporary narratives exhibit with alacrity and gusto—which (as in the case of House of Cards), if it were not so expertly entertaining, would be seriously worrisome.