March Madness for Book Lovers

It’s March and the Great AMERICAN NOISE MACHINE is ratcheting up the decibels, promoting the hysteria known worldwide as March Madness. The 75-year-old basketball tournament, which began with 8 teams competing, has turned into an international spectacle with almost 70 teams in the hunt for a collegiate championship—and the bragging rights and dollars that are attached. (By the way, the rubric originated with the Illinois High School Boys Basketball Championship.)

The fact that so many people have become involved in what is now commonly called “bracketology”—who under ordinary circumstances couldn’t distinguish long division from Division One—is perhaps a singular clue pointing to the eventuality of March Madness being adopted as a legitimate syndrome by the American Psychiatry Association. The images of madness exhibited in American culture have traditionally ranged from silly and banal to horrific—from people painting themselves in school colors and wearing silly accoutrements and/or rioting in the streets, to the images presented in films attempting to make some kind of statement about the mentally unhealthy (such as The Snakepit or One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest or Girl, Interrupted, all films, by the way, adapted from bestselling books).

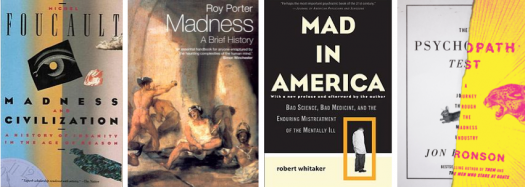

There is certainly a substantial bibliography accessible to any one interested in the protean topic of insanity:

• Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason by Michel Foucault

• Madness: A Brief History by Roy Porter

• Mad in America: Bad Science, Bad Medicine, and the Enduring Mistreatment of the Mentally Ill by Robert Whitaker

• The invaluable The Psychopath Test: A Journey Through the Madness Industry by Jon Ronson

This focus on mental illness brings to mind the great Christopher Lasch’s insightful The Culture of Narcissism where his characterization of “The Me Decade” noted the rise of a “therapeutic sensibility”— opining that “People today hunger not for personal salvation, let alone for the restoration of an earlier golden age, but for the feeling, the momentary illusion, of personal well-being, health, and psychic security.” Lasch also asserted that the helping professions had become practitioners of a new form of “priest craft.” Not exactly the acerbic tone of the great Viennese satirist Karl Kraus’s observation, “Psychiatry is the disease of which it is the cure,” but equally damning.

Books continue apace to be published on all aspects of mental health, including personal narratives and biographies of the variously afflicted. Curiously (or not), three American women artists, by way of their suicides, have provided more than a few feet of shelf space to the subject—Anne Sexton, Diane Arbus, and Sylvia Plath. Although for the moment interest in Arbus and Sexton seems to have abated, there are three new books on Sylvia Plath, the American poet who killed herself at the age of 30.

Andrew Wilson’s Mad Girl’s Love Song: Sylvia Plath and Life Before Ted (Scribner) doesn’t add much to Anne Stevenson’s authoritative 1989 biography Bitter Fame. But he does manage to find Plath’s lover before her Ted Hughes, Richard Sasson. Sasson refused to be interviewed, but supplies stories he had written that offer a glimpse of the raging Plath, bipolarity and all.

In American Isis: The Life and Art of Sylvia Plath, Carl Rollyson (St Martin’s Press) asserts that “Sylvia Plath is the Marilyn Monroe of American Literature,” as he casts new light on Plath’s life, benefiting from access to the new Ted Hughes archive at the British Library, which contains 41 Hughes-Plath letters and other previously unpublished materials.

Pain, Parties, Work: Sylvia Plath in New York, Summer 1953 (Harper) is Elizabeth Winder’s speculative account of the 21-year-old Plath’s visit to New York, which according to Plath changed the course of her life.

No account of the Plath bibliography can ignore Janet Malcolm’s three-part Annals of Biography in the New Yorker in the summer of 1993, which was published the next year as The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath & Ted Hughes (Knopf)—not least because of its controversial defense of Hughes, who was to Plath idolaters akin to the antichrist. Caryn James wrote in the New York Times, in “The Importance of Being Biased”:

Few essays in recent years have caused anything like the buzz The Silent Woman did when it first appeared, but Sylvia Plath was the least of it. While the English fuss about poets’ graves, Americans gossip about litigation and celebrity journalists. The word was that The Silent Woman was all about Janet Malcolm.

Well, it’s certainly not about Plath, who emerges as an enigma, a shadowy set of contradictory anecdotes. Some say she was mad, others maddening; she may well have been both.

As 24-year-old New York Post reporter Susannah Cahalan writes of her memoir Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness (Free Press), “[It] chronicles the swift path of my illness and the lucky, last-minute intervention led by one of the few doctors capable of saving my life. As weeks ticked by and I moved inexplicably from violence to catatonia, $1 million worth of blood tests and brain scans revealed nothing.” It’s a truly harrowing descent into madness with shadings of a medical thriller as Cahalan is wracked by terrifying hallucinations, intense mood swings, insomnia, and fierce paranoia. She recalls:

At first, there’s just darkness and silence.

“Are my eyes open? Hello?”

I can’t tell if I’m moving my mouth or if there’s even anyone to ask. It’s too dark to see. I blink once, twice, three times. There is a dull foreboding in the pit of my stomach. That, I recognize. My thoughts translate only slowly into language, as if emerging from a pot of molasses. Word by word the questions come: Where am I? Why does my scalp itch? Where is everyone? Then the world around me comes gradually into view, beginning as a pinhole, its diameter steadily expanding. Objects emerge from the murk and sharpen into focus.

I know immediately that I need to get out of here.

The literature of and about Madness is fascinating and endless, especially as it admits narratives and perspectives as numerous as those that have inhabited this planet. Bedlam, London and Its Mad by Catherine Arnold is the history of the British hospital first dedicated to the housing of the insane. And listing the literature of insanity is incomplete without including Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, by depressive Thomas Penson De Quincey, and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Kubla Khan, by the bipolar Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

———

About the author: Robert Birnbaum’s Social Security number ends in 2247. He lives in zip code 02465 and area code 617. He was born in the 2nd month of a year in the 20th century. He doesn’t social network (used as a verb) except through his Cuban retriever Beny (named after Beny More, the Frank Sinatra of Cuba). Izzy Birnbaum also has cloud storage and uses electronic mail. He hopes his son Cuba is the second coming of Pudge Rodriguez. He mutters to himself at Our Man In Boston.