Thousands of Words: Galleries in Books

One wonders if pop culture’s preoccupation with novelty, the dazzling shine of newness, its inescapable immediacy—mixed with an endless outpouring of images—has diminished the import of photographic art. In a visually top-heavy information stream, all manner of forces and influences have us looking at more pictures while our comprehension and retention of them decreases. What does it say that more than 25 percent of photos taken today are with a smartphone? I don’t doubt that some fantastic images are created through our portable digital appliances, but …

Fortunately, serious photography and pricey photographic books continue to be published, the flame kept alive by a good number being attached to significant photographic exhibitions. Here’s a sampling of recent monographs and anthologies, some resurrecting older work that speaks to the timeliness and timelessness of the photographic image.

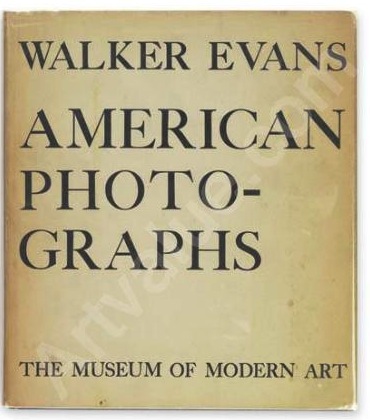

Young photographer Walker Evans was given an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1938 and coincident with its seventy-fifth anniversary, MOMA has republished the monograph that attaches to the exhibit.

Documentary photojournalist and longtime Magnum member Leonard Freed (who passed away in 2006), known for his 1968 tome, Black in White America (Getty Publications), documented the Civil Rights Movement, traveling with Martin Luther King on his march from Alabama to Washington DC. Now comes This Is the Day: The March on Washington (Getty Publications), with an illuminating essay from Michael Eric Dyson and foreword by veteran civil-rights activist Julian Bond.

Freed started photographing postwar Germany in 1954 and published that work in 1970. Made in Germany (Steidl) has been republished to coincide with an exhibition at the Museum Folkwang in Essen that just ended. A useful explanatory tome, Remade: Reading Leonard Freed, is included.

I spoke with Abelardo Morell ten years ago, and it’s clear that the past decade has been a productive one for him. The Art Institute of Chicago is hosting a retrospective exhibit of Morell’s work, The Universe Next Door, along with an anthology of Abe’s greatest hits from his child photos to the Gardner project to his camera obscura and tent photos. You’ll find my recent chat with Morell here.

Harry Callahan’s life coincides with most of the twentieth century. When he died in 1999, he left behind 100,000 negatives and more than 10,000 proof prints. So consider the task of curating a retrospective of Callahan’s long and productive and multi-faceted career—which is the challenge Dirk Luckow and Sabine Schnakenberg took upon themselves in assembling Henry Callahan: Retrospective (Kehrer Verlag). It’s a splendid book, and if you are in the neighborhood or are inclined to travel to Munich, you can view the retrospective through October 27, 2013, at Münchner Stadtmuseum.

Hungarian photographer André Kertész’s forte was the photo essay (On Reading is one of my favorites), and in what is now a frequent occurrence, previously unpublished photos have come to light. Kertész returned to Paris after World War II, and in 1963, he took more than 2,000 black-and-white photographs and nearly 500 slides, which he edited for the purpose of publishing a book—a project he failed to complete. Thus we have André Kertész: Paris, Autumn 1963 (Rizzoli).

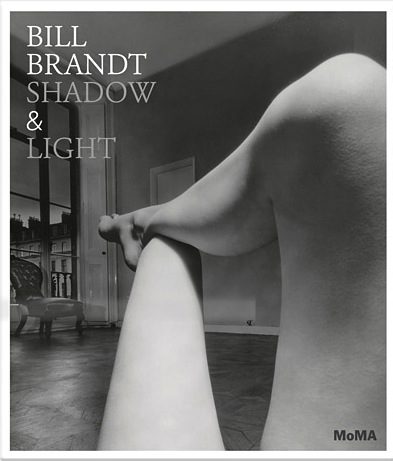

Bill Brandt’s Shadow and Light recently resided at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and the accompanying book, Shadow and Light (The Museum of Modern Art), by curator Sarah Hermanson Meister with Drew Sawyer, is a well-published reference to its originating exhibit and a useful guide to understanding Bill Brandt anew. You can access a PDF of the monograph.

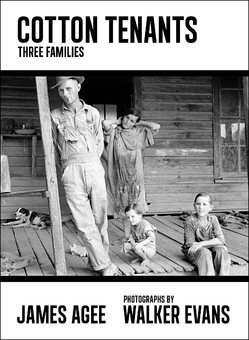

Before television (in fact, before rural electrification), periodicals did what some TV programs still attempt to do. Before Henry Luce invented Life magazine, his pet project was Fortune (upon which he concentrated his fawning attention and lavished many a dollar). James Agee, before he made his mark, was hired to travel to southeastern Alabama to write about white tenant farmers. He was joined by Walker Evans and they spent two months in Hale County, Alabama, living with three different tenant families. The fruits of that project were never published until recently. In Baffler #19, editor John Summers takes great pride in uncovering and publishing a good chunk of this mislaid gem in Cotton Tenants: Three Families (Melville House).

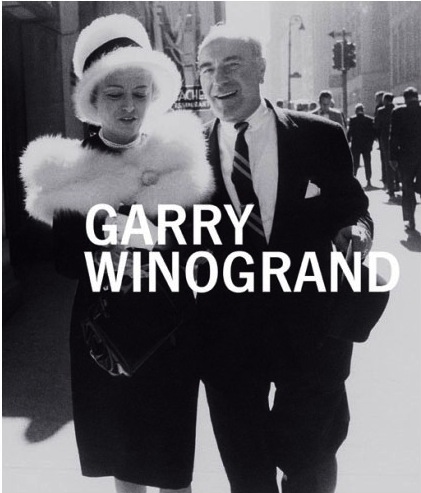

Garry Winogrand, who died in 1984 at the age of fifty-six, left a legacy of thousands of unprocessed rolls of film (some 250,000 frames), as well as a body of work that, by unanimous acclaim, place him in the pantheon of American photographers. One hundred of those previously unprinted photographs were in an exhibition at San Francisco’s Museum of Modern art through June 2 (then on to Manhattan, Paris, and Madrid). Accompanying this exhibition is a 474-page monograph edited by Leo Rubinfien, simply titled Garry Winogrand (SFMOMA/Yale University Press). Rubinfien writes, “The hope and buoyancy of middle-class life in postwar America is half of the emotional heart of Winogrand’s work. The other half is a sense of undoing.”

There is no shortage of erotica/pornography (you decide) available to photo enthusiasts and hungry libidos. Mikhail Paramonov unabashedly fills Wild Lolitas with 300 pages of “budding flowers” who “are free, wild and intoxicatingly arousing.” Belgian Marc Lagrange is characterized as a nude photographer and Diamonds and Pearls (te Neues) is his latest opus, in which he labors to imitate the timelessness of the Old Masters. Henrik Purienne’s new work, Purienne (Prestel Verlag), is a collection of snapshots and portraits taken between Cape Town, Los Angeles, and the South of France over the past three years.

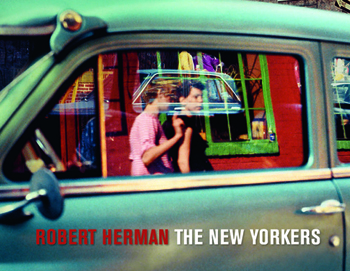

New York, being a world capital (and major center of ambition), is an all-too-frequent geography for photographers trolling for subjects—not necessarily a bad thing in and of itself. Robert Herman does splendidly with his self-published monograph The New Yorkers (Proof Positive Press I), not the least because the images were shot with the late lamented Kodachrome film from 1978 through 2006.

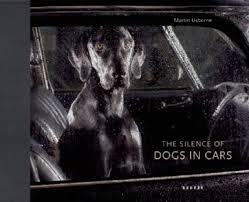

Londoner Martin Usborne photographs dogs (among other animals), and he eschews the kitchiness of William Wegman. His latest opus, The Silence of Dogs in Cars (Kehrer Verlag), is a compelling array of hounds in cars. Usborne explains, “When I started this project I knew the photos would be dark. What I didn’t expect was to see so many subtle reactions by the dogs: some sad, some expectant, some angry, some dejected. It was as if upon opening up a box of grey-coloured pencils I was surprised to see so many shades inside.”

San Francisco gallery owner Jeffrey Fraenkel curated and edited The Unphotographable (Fraenkel Gallery), an anthology exploring the history of that which cannot be photographed. Comprised of approximately fifty works, a wide range of photographers are represented including Alfred Stieglitz, Sophie Calle, Man Ray, and Glenn Ligon, as well as works by anonymous and unknown photographers.

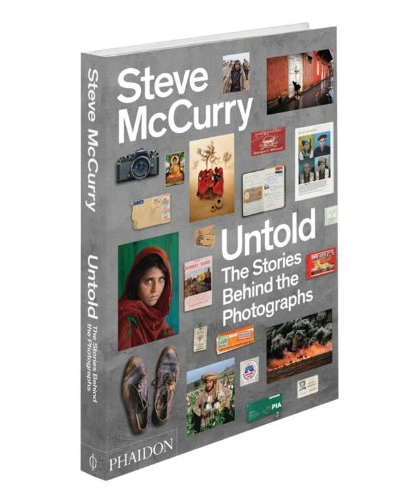

You may not know Steve McCurry by name, but his thirty-year career has produced images with which you are probably familiar. His new book, Steve McCurry Untold: The Stories Behind the Photographs (Phaidon), presents the background behind fourteen of what McCurry judges to be his most important assignments, including more than 100 images representative of his body of work, as well as notes and ephemera from a very productive career.

British photographer Vanessa Winship, 2011 recipient of the Henri Cartier-Bresson Award (which funds an artist to pursue a new photographic project) crisscrossed the United States in pursuit of the fabled “American dream.” she dances on Jackson (Mack) contains sixty-four black-and-white images from that project. Sean O’Hagan observes:

Winship’s photographs are all about suggestion. What emerges cumulatively is an America of the imagination: her own imagination, of course, plus the received traces of other photographers who traversed the continent before her: the inevitable Walker Evans and Robert Frank—she actually sought out a site in Montana that Frank photographed in The Americans … Winship’s decision to shoot America in black and white, though, lends these images another layer of suggestion, a haunted quality.

———

About the author: Robert Birnbaum’s Social Security number ends in 2247. He lives in zip code 02465 and area code 617. He was born in the second month of a year in the twentieth century. He doesn’t social network (used as a verb) except through his Cuban retriever Beny (named after Beny More, the Frank Sinatra of Cuba). Izzy Birnbaum also has cloud storage and uses electronic mail. He hopes his son Cuba is the second coming of Pudge Rodriguez. He mutters to himself at Our Man In Boston.