A Whole Lotta Soul

The music closest to my heart (and soul) has been jazz, blues, rumba, son, reggae, soca, R&B, and—later in life—gospel. (This, despite being a godless Jew.) Growing up in Chicago helped. It was home to the powerful WVON (Voice of the Negro) AM radio station; Holmes “Daddy-O” Daylie’s Jazz Patio; and, after midnight on WCFL (the Voice of Labor), the quintessential jazz deejay Sid McCoy. There were, of course, Chicago’s versions of the Apollo, the Regal Theater, and down-home blues clubs like Theresa’s.

However, books on music are rarely interesting to me, except that recently a number of books have caught my eye (and ear). Concomitant with ruminating on these tomes, I have been listening almost exclusively to gospel music, especially Mavis Staples and Marion Williams. If this condition persists, I may have to see a physician or a rabbi. In no particular order, here is some reading for that “hole in your soul.”

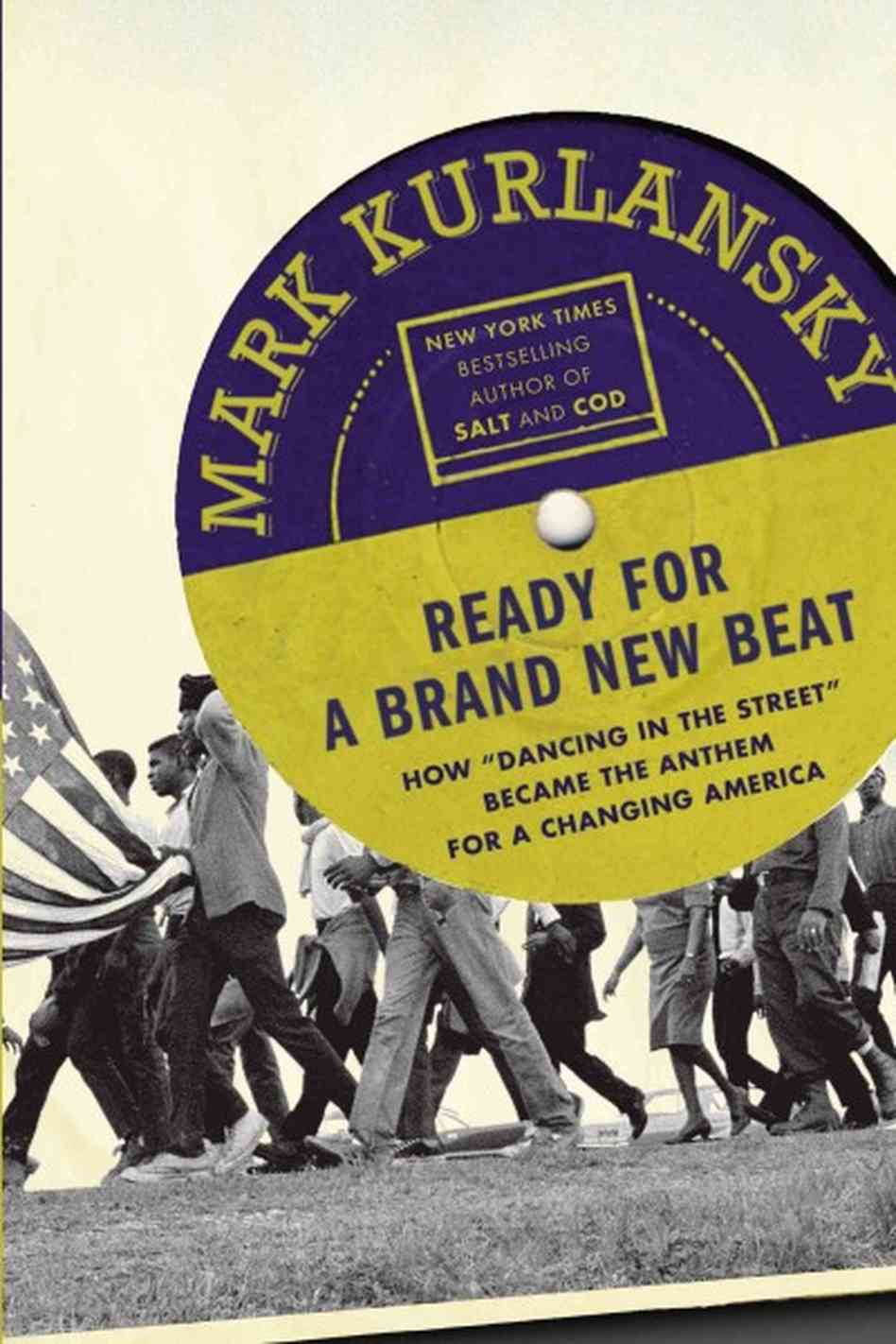

Much has been written in recognition of the music machine that Berry Gordy Jr. created with Motown Records. As Mark Kurlansky tells it in Ready for a Brand New Beat: How “Dancing in the Street” Became the Anthem for a Changing America (Riverhead), in the summer of 1964, Marvin Gaye, William “Mickey” Stevenson, and Motown songwriter Ivy Jo Hunter wrote an upbeat dance tune, “Dancing in the Street,”that was fueled by a transformational year. The song is not that interesting, but Kurlansky’s use of the song (one of only fifty preserved by the Library of Congress in the National Recording Registry) is a useful lens. And he has a fine eye for collecting poignant snapshots of the sixties, as they became a defining decade.

Even though it is thirty years old, Nelson George’s Where Did Our Love Go? The Rise and Fall of the Motown Sound (St. Martin’s Press) remains an engaging and useful account of Gordy’s talents and business practices in creating the enterprise that brought the Supremes, the Jackson Five, Smokey Robinson, the Miracles, the Temptations, Marvin Gaye, the Four Tops, and Stevie Wonder to mainstream (white) America. An amalgam of juicy anecdotes, nuggets of gossip, and corporate history, George details Motown’s/Gordy’s approach to talent management and the manufacture of stars, which included styling, choreography, in-house production and songwriting, and skillful publicity. To some degree Motown became the template for the modern recording industry. Yet beyond a very commercial approach to record promotion, the legacy of music created by Gordy is proof that, above everything else, Motown Records understood (as its slogan announced), “It’s What’s in the Grooves That Counts.”

Gerald Posner is a skillful investigative reporter who has written books on the Martin Luther King Jr. assassination, erstwhile presidential candidate Ross Perot, and the children of Third Reich leaders. Almost every Motown star published an autobiography, so Posner took up the history of “Hitsville USA” in Motown: Music, Money, Sex, and Power (Random House). By 2002, almost every relationship between singers, songwriters, producers, and the label ended up in litigation, which at the time was a largely untold story. Posner spent a considerable amount of time in the basement archive of the Wayne County Court in Detroit, where twenty file cabinets are devoted to litigation just between Gordy and the songwriting team Holland-Dozier-Holland.

Posner discloses that Gordy dreamed up strict rules. Motown lyrics had to be in the present tense. Motown singers were not to frown or snap their fingers. Dance moves were meant to be exciting, but booty shaking was not allowed. The stories around Motown Records, some perhaps apocryphal, make for a fascinating study.

I first encountered Arthur Kempton when he took over as the announcer for MIT’s FM radio station’s Sunday morning soul music program, “For Lovers Only.” Kempton’s knowledge of and love for the music he played was as impressive as the potency of the playlists he put together. Thus it was with great relish that I read his Boogaloo: The Quintessence of American Popular Music (Pantheon). As a detailed history of black American music, it’s a fiercely zealous account, where Kempton asserts that Mick Jagger looted American culture and that Janis Joplin was a second-rate screamer. He uses gospel patriarch Thomas Dorsey, soul singer Sam Cooke, entertainment mogul Gordy, and visionary George Clinton as touchstones for examining both black culture and black music against a larger social context. In Boogaloo—a word that Kempton prefers to the term “rhythm and blues”—he runs a narrative thread from Dorsey through Mahalia Jackson, Aretha Franklin, and James Brown to Cooke to Gordy to Stax records to Clinton and the murders of Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls, and the story of Death Row Records.

In my 2003 conversation with Kempton, he said:

In a lot of ways the purest lens on American history is black history as in some ways a pure lens on Czarist history would be to look at the history or experience of Jews in Russia. Since black Americans have been here as long as the Cabots and the Lodges and Randolphs and the Masons, you have that whole epic sweep of American history that you can look at. And, of course, the music business affords the opportunity to look at the creation and rise of the youth market. One of the ways of looking at this book is that since their manual labor became obsolete, black America’s popular culture has been its most fungible natural resource.

Peter Guralnick proved himself an able musicologist and cultural historian with his seminal two-volume study of Elvis Presley. Given Cooke’s stature and accomplishments, it’s fortunate that Guralnick has focused his considerable reportorial skills and on talents Dream Boogie: The Triumph of Sam Cooke (Little, Brown). Coming to a bad end in a fleabag Los Angeles motel in 1964, Cooke is remembered for his paean to the civil-rights movement, “A Change Is Gonna Come.”

As we learn from the nearly 800-page Dream Boogie, Cooke was so much more than that. A talented singer and songwriter, he was the black equivalent to Presley and one of the first black Americans to “cross over,” as mainstream success was called. And he was a bona fide celebrity linked to and appearing with movers and shakers such as Martin Luther King Jr., the then Cassius Clay, Malcolm X, James Brown, Harry Belafonte, Aretha Franklin, Fidel Castro, the Beatles, Sonny and Cher, and Bob Dylan. And in addition to a rigorously researched and nuanced account of Cooke’s tragically short life, Guralnick captures the ambience of 1940s Chicago, aka Bronzeville, where Cooke and his seven siblings were raised by his metal-worker and professional-preacher father.

In I’ll Take You There: Mavis Staples, the Staple Singers, and the March up Freedom’s Highway (Scribner), Chicago Tribune music critic Greg Kot contributes another one of those handful of music books that not only gives a good account of a life but provides an illuminating context for that life. I was certainly aware of the Staple Singers, but not of their worldwide popularity and their lifelong commitment to maintain the integrity of their faith-based music and social justice. Nor was I familiar with Pops Staples’s profound influence on blues guitar styles by way of his signal tremolo sound. Kot follows the Stapleses’ career from their early church gospel performances to pop stardom with songs such as “I’ll Take You There” and “Respect Yourself” and the nonpareil Mavis Staples’s solo career. (One gossip note: Bob Dylan wanted to marry Mavis, all those many years ago, a path not taken that she regrets to this day.) Kot has done the Stapleses a great service and rendered a comprehensible picture from the turmoil of their era. Septuagenarian Mavis is still ably kicking out the jams and taking us there.

Bettye LaVette’s story is amazing. After early success in the Detroit of her youth, singing the hit “My Man He’s a Lovin Man” at the age of sixteen, she spent the next four decades in a limbo of relative obscurity, singing in clubs and lounges. LaVette, aided by David Ritz, chronicles her rollercoaster life from teen sensation to comeback queen in A Woman Like Me (Blue Rider Press), and there’s a lot about sex. LaVette unflinchingly tallies the many R&B legends she slept with: Otis Redding, Solomon Burke, Ben E. King, Gene Chandler, Jackie Wilson, and more. LaVette opines, “Unlike singing and cooking, I can’t say that sex is better than ever.”

Type “Mary Wells” in the search bar on Spotify or Pandora and you will be rewarded with a plethora of pure unadulterated pre-cookie cutter Motown. From 1960 to 1964, Wells had a string of hits, including “Bye Bye Baby,” “I Don’t Want to Take a Chance,” and “You Beat Me to the Punch,” culminating in her greatest hit, “My Guy,” and an invitation to tour England with a group called the Beatles.

Peter Benjaminson’s biography Mary Wells: The Tumultuous Life of Motown’s First Superstar (Chicago Review Press) does the usual recounting of sexual havoc and substance abuse found in the music business, but as a veteran observer of Motown (this being his third book on that subject), Benjaminson is also savvy enough to provide substantial details of Wells’s relatively brief success and long decline, shining some light on some of the darker corners of the Motown story.

Motown’s business model involved using the revenue from successful artists to support the careers of developing ones, such as (at that time), the Supremes. This didn’t sit well with Wells, who announced her intention to leave the label. She claims Gordy offered her 50 percent of the company, which meant that, had she stayed, she would have had a substantial stake in Motown’s incredible success. Years later, Gordy offered, “I would not always pay what it would take them to stay. That might have been a mistake.” When asked, Wells unabashedly told a reporter, “I should have stayed at Motown.”

Many of the interesting revelations are culled from four hours of previously unreleased and unpublicized deathbed interviews by journalist Steve Bergsman with Wells. Benjaminson also draws upon years of interviews with Wells’s friends, associates, lovers, and husbands. After a lifelong two-pack-a-day cigarette habit, Wells died of lung cancer in 1992. Fellow Motown artist Brenda Holloway recalls that “there was a sadness about her from the first day I met her to the last day I saw her.”

Though a number of these books touch on the Chicago black music scene, I am struck by an egregious lack of attention paid to Chicago’s late lamented reigning prince of soul, Curtis Mayfield—singer, songwriter, arranger, producer, entrepreneur, talent scout. Mayfield’s hits with the Impressions (“People Get Ready,” “Gypsy Woman,” “It’s All Right,” “We’re a Winner”), his soundtracks for Super Fly and Short Eyes, his work with the modern version of Okeh records (Major Lance, Billy Butler, Walter Jackson, and the Artistics), and the creation of Curtom, were key elements in the lush and verdant musical fields of Chicago—and the creative equal to anything produced in Detroit’s Motown or Memphis’s Stax. Chicago clearly joins those two metropolises to form the prevailing troika of American soul music. (Arguably New Orleans is close but doesn’t meet the criterion of national influence.) And Mayfield’s mastery in both the creative and business of making recorded music in Chicago warrants a serious ethnomusicological biography by a writer of the stature of Peter Guralnick, Nick Tosches or Arthur Kempton. Of course, if an enterprising editor were to consider a reasonable advance, I would be up for the challenge of writing that book.

Editor’s note: For more reading on this topic, we highly recommend:

- “Love Is Here and Now You’re Gone” by Garret Keizer (Fall 2013 VQR)

- “Sister Cities” by Preston Lauterbach, along with his Spotify playlist (Winter 2014 VQR)