1.

I misplace an earring in my hotel room in Santiago, Chile. So I ask the head housekeeper, Patricia, if anyone has found it: a silver lotus leaf, not valuable, but special to me because it’s a good luck charm.

“Nothing can get lost here,” Patricia says. It takes me a minute to note her alarm, maybe even offense. “Don’t worry about it,” I say, but she insists: “Nothing—I mean nothing—can get lost here. Even if it looks like garbage to us, even if it’s a little bit of water left in a bottle. Because if people complain? Oof. Even if they miss a receipt that maybe they dropped on the floor and it’s crumpled up and torn and looks like garbage—we can’t throw it away! Because maybe the customer needs it to justify an expense. One time I threw away this soap because it looked horrible”—she cringes and scrunches her nose at the nightmarish soap—“but it was made special for this person, and I had to dig in all the garbage bags to find it. If you’re new here and something gets lost, they may give you another chance. If it happens again you’re sent away. But if they trust you—I’ve been here nineteen years—and suddenly something is lost, it’s not good. But plenty of times clients say they lost something but they have it with them, or forgot where they put it.”

I spent my ten days in Chile looking for that earring. I never found it, but I never mentioned it to anyone.

2.

Cecilia has been working in the same hotel in Santiago for seven years. “I like it a lot,” she says. Patricia, whose job is to inspect Cecilia’s work, is within earshot, so I wonder if she really means it. “When I started, I was nervous, because it’s difficult to get a job like this one. With health benefits, twenty-one days of paid vacation, and they pay you on time. This kind of job you get if you know someone. You need to be trusted. And it starts you at 300,000 pesos, more than minimum wage. Now I make 380,000 a month. And that’s good for Chile, especially now because foreigners come and start working for less and they change jobs frequently just to get paid more. Now everything concerning work is very unstable.”

Foreigners? I ask.

“You know, Haitians and Dominicans—so many of them. And we try to stay open-minded, but they don’t come to Chile as professionals, they’re not architects or engineers. They are workers like us, people of the pueblo, and they work, undocumented, for no money. Those of us from Chile were here when it was tough. We struggled for jobs with benefits, and now foreigners come to Chile to take advantage of what we worked hard for.” Patricia adds, “I was a child during the dictatorship. But I was born into it, so it was normal, a way of life. It’s true that at night we had to stay home, everyone inside. We couldn’t speak about politics or listen to music—none of the music from the Left or even the poems of Neruda. But us workers, all we wanted was to be left alone. There was no delinquency, no drugs. It was a country of tranquility. The streets were quiet. We didn’t know people were going missing because it wasn’t in the news. We learned later. If we had been Communists, it would’ve been different, because they were pursued. But my mother was a teacher, and we just worked, like we work now.”

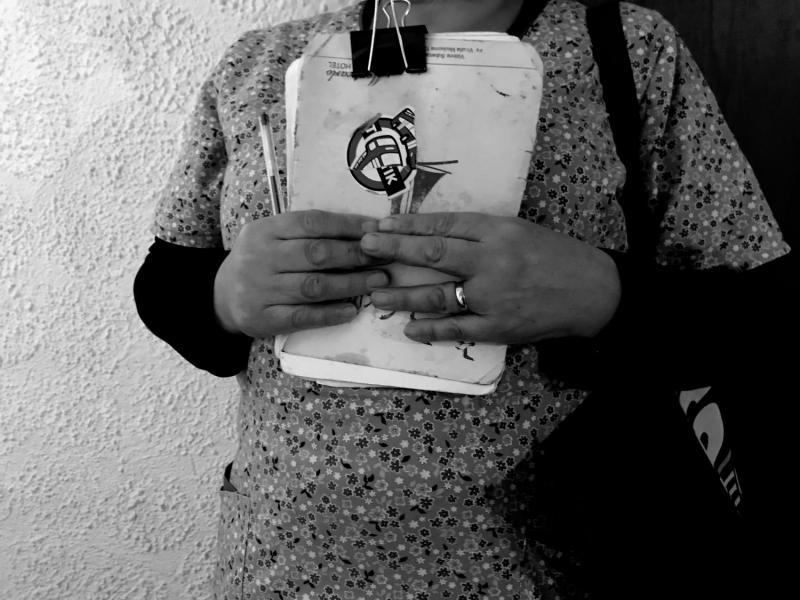

Patricia holds a clipboard, Cecelia leans on her broom. They clearly agree. “Look, if you don’t know something bad is happening, you live in peace. Now people make it seem like it was all bad. But for us, it was life.”

3.

“Here at work we help each other,” Cecilia says. “But of course there are some unjust things—” She looks around to see if anyone is listening, then says: “For example, this floor is not mine. Everyone has their own floor. My floor is the hallways of the fourth floor. I do all those floors one day but then sometimes also the floor assigned to no one. But let’s say the day I take off is the day the client leaves a tip. Even if I’ve been cleaning that room every day, my colleagues take the tip. They don’t save it for me, because money is for the moment. When you see it, you take it. So when people stay many days at the hotel, if you’re unlucky you don’t get those tips. It’s better when clients tip every day. That way, whoever cleans that day gets the tip. But many people don’t know that. Even if I love my work—because we’re like a family here—it’s not easy. We all get one day off a week, and one Saturday and Sunday a month. We work forty-five hours a week. When someone takes the day off we have to work double the rooms, but at the same salary. And what we make covers the basic needs like rent and food, if we’re lucky. Nothing else. Sometimes the hotel pays me in advance when I’m in need but then the next month I’m in trouble.” Then she looks at me straight in the eye and asks, “How many hours do you work? How much do you get paid?” I don’t answer. I am embarrassed to say. I’m a professor who goes to campus two days a week, maximum three days. So I say nothing.

4.

After all these years working at the hotel, with guests from all over the world coming and going, I wonder what Patricia has learned about people.

“That love does not exist,” she says, turning her wedding ring. “We have a client that comes with his wife one week and then with his lover the next. He lives 350 miles away, far enough that neither woman will ever just show up. Always asks for room 62, because it’s big and has a tall table where he can work. He likes that it has big windows. And it’s complicated for us because his wife is a lovely woman and always makes conversation with us. And we can’t say anything. Nothing. You know, many men do the same thing, but never have I seen a woman do such a thing. Never! It’s not just the cheating, it’s the way he is with his wife. Real tender. But then he turns around and acts the same with the lover. So it makes you lose trust in men. Me and my husband have twenty-six years together—a life! We’re family. We’re comfortable and I’m loyal. He’s the person I will be with for the rest of my life, and if we’re separated or he died I don’t think I’ll ever marry again. But the only love I believe in is the love of children, or the love of my sisters. But the love of a man? No.”

I look away from Patricia toward Cecilia, who leans against the mop all dreamy eyed. She says, “I believe in love. Yes. I do.” She tells me she has been divorced fourteen years and didn’t think she’d ever marry again. But then she met someone, a colleague here, and she’s certain that he loves her. They’d been working alongside each other for five years and she didn’t have a clue that all along he was interested in her. They’ve been together two years now. “I’m so happy, completely happy,” she says. “My children adore him. He adores me. When someone at work told me he liked me, I said I didn’t believe it. Back then I thought, Who will possibly ever like me?” I look at Patricia and she’s nodding: Yes, it’s true. He does love her.

These dispatches are from #VQRTrueStory, our social-media experiment in nonfiction, which you can follow by visiting us on Instagram: @vqreview.