Four Different Ways of Looking at How “Things Fall Apart”

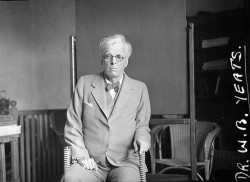

In honor of William Butler Yeats’s birthday (June 13, 1865, in Dublin), contributor Kevin Smokler looks at the historical echoes of one of the poet’s most immortal stanzas.

“Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the center cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world.”

These four lines are half of the opening stanza of William Butler Yeats’s 1919 poem “The Second Coming.” Composed of twenty-two lines in two stanzas, “The Second Coming” is one of Yeats’s most beloved and often-read works. Written in 1919 and published the following year, the poem is commonly thought to be an interpretation of the savagery of World War I and the apocalyptic moment Europe had reached immediately following it. Earlier versions (several of which survive) are more specific, as though Yeats had national instead of continental or worldwide upheaval in mind. Literary critic Harold Bloom has submitted that the poem refers to the Russian Revolution of 1917. Either way, it is quite clear that “The Second Coming” is about a moment in history when the past has been obliterated and the future is unknown but arriving any dark minute now. There is great fear in the land Yeats has created—fear borne not of the inescapability of change but of the uncertainty of exactly what that change will be. Yeats ends with this immortal image:

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

Yeats has reached all the way to the birth of Christ for much of the poem’s visual power. The title and double repetitions of the phrase “The Second Coming,” the references to “twenty centuries” and “Bethlehem” recall the Book of Revelation and the coming of the apocalypse. The apocalypse and the Second Coming of Christ are of course another fulcrum where one eon is ending, another about to begin. But as any believer will tell you, “the future” of the Christian Second Coming is not uncertain at all. You just have to go through hell to get there. The phrases “widening gyre” and “beast” complicate what kind of future we are to expect even more. Will the era to come be governed by beasts? A “widening gyre” is a spiral getting bigger and further away from center, never to return to its point of origin, what it once was and knew.

***

Things Fall Apart is the debut novel by the Nigerian author Chinua Achebe. Published in 1959, it is considered the most important novel in modern African literature and the first written in English by an African author to achieve worldwide acclaim and readership. Things Fall Apart is the story of three years in the life of Okonkwo, a village leader and wrestling champion in late nineteenth-century Nigeria, just before the arrival of European missionaries. It has sold over 10 million copies, has been translated into fifty languages and is read in high schools throughout the world. Time magazine included Things Fall Apart on their 2005 list of the 100 greatest novels of the twentieth century.

Achebe structured Things Fall Apart as a Greek tragedy—a hero whose strengths mask the shortcomings that will ultimately lead to his undoing. He has also added the dimension of the larger world changing irrevocably just beyond the borders of Okonkwo’s understanding. Within the novel, Achebe deals with a great many things—ambition in conflict with family loyalty, tradition in a tug-of-war with change, an African story with Africans at center stage instead of bystanders to European colonialism, written in a European language but aimed at a worldwide readership. But, surrounding it, like trees at the edge of a clearing, is the all-too-human fear of looking into an uncertain future, a fear that transcends race, nation, continent, even the old-fashioned definition of tragedy. Exactly how much can we blame someone for not accepting a future they can’t do anything about?

The chaos of mind that results from those impossible circumstances is evident both from the swift, sad act of violence that concludes the novel and from the passage of poetry that opens it.

***

In 1968, a decade after the publication of Things Fall Apart, Joan Didion published Slouching Towards Bethlehem, her first collection of nonfiction. Slouching Towards Bethlehem contains twenty essays divided into three sections—“Life Styles in the Golden Land,” “Personals” and “Seven Places of the Mind.” Didion’s subject in sections I and III (the largest two) was California in the late 1960s, the state where she had been born and which had elbowed itself into the cultural spotlight thanks to psychedelia, rock ’n’ roll, and the Technicolor happenings in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district. “The market was steady and the G.N.P. high…” Didion wrote in the title essay. “It might have been a spring of brave hopes and national promise … At some point we had aborted ourselves and butchered the job.”

Didion had been an editor at Vogue and published her first novel, Run River (1963), while on staff there. It was Slouching Towards Bethlehem five years later that made her reputation both as one of her generation’s great nonfiction storytellers (in league with Tom Wolfe, Hunter S. Thompson, Norman Mailer and Gay Talese) and as someone who understood the grim horror at the heart of the social revolution of the sixties. If the future foreseen by the missing children in Haight-Ashbury when Joan Didion showed up was communal, peaceful, and beyond hatred and war, what Didion saw was “a country of bankruptcy notices and public-auction announcements and commonplace reports of casual killings.”

Didion would wait ten years before publishing another essay collection, The White Album, in 1979. The White Album takes its title from the colloquial name for the Beatles’ ninth album (the band simply called it “The Beatles”). The title essay (the entire first section of the book) is Didion’s autobiographical look at the 1960s while living in Southern California. The fifth and concluding section of The White Album is titled “On the Morning After the Sixties.” The White Album is a book self-conscious of the decade it is examining. It is a book looking back at something that is gone. Its predecessor, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, is an attempt to understand a decade as it is happening.

The closing essay of Bethlehem is called “Goodbye to All That” and is Didion’s account of moving back to California, of leaving New York, the city that held her early adult life and the realization that “at some point the golden rhythm was broken, and I am not that young anymore.” We have just read an entire book on California, on the frightening, confusing change happening there, and now Didion, the detached, stone-faced observer, concludes with her not leaving but returning to it. “Goodbye to All That” seems here to refer to both New York and a sense of being able to draw tangible conclusions. Didion does not know where or how the center currently not holding will end up. She does not even offer to find out. The opening of “Goodbye to All That” tells as much: “It is easy to see the beginnings of things, and harder to see the ends.”

***

Things Fall Apart is the fourth studio album by the Philadelphia hip-hop band The Roots. Released in February of 1999, it is considered the group’s breakthrough effort, their first certified platinum record that also won them their first of four Grammy Awards. Named after Achebe’s novel, Things Fall Apart is now considered a seminal record both of the period in hip-hop music and in the career story of The Roots themselves, the point of no return where the musicians no longer belong to their initial fans but to the culture at large.

Things Fall Apart was also the first Roots album to be named after a work of literature, a convention they would return to on their sixth album, The Tipping Point (after Malcolm Gladwell’s book of the same name) and their eighth, Rising Down (after William T. Vollmann’s seven-volume study of violence, Rising Up and Rising Down). As of this writing, The Roots have released thirteen albums, were named one of the world’s greatest live bands by Rolling Stone magazine, are the house band on the television show Late Night with Jimmy Fallon and are considered likely contenders for induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Things Fall Apart begins with a vocal collage, an argument taken from the Spike Lee film Mo’ Better Blues, set to a jazz beat.

Musician #1: “If we had to depend on black people to eat, we would starve to death … You on the bandstand … What do you see? You see Japanese, you see … you see West Germans, you see Slobovic, you know, anything, except our people, man…”

Musician #2: “Everything, everything you just said is bullshit. If you played the shit that they liked, then the people would come. Simple as that.”

The musicians are talking about jazz. At that moment, The Roots insert a third voice, from a different source, which says:

“Inevitably, hip-hop records are treated as though they are disposable. They are not maximized as product, not to mention as art.”

The remainder of Things Fall Apart is a rebuke to that statement. In the late 1990s, hip-hop music had experienced both an explosion in popularity and a narrowing of the form’s acceptable styles. Hip-hop music that glorified money, sex, and violence and was meant for dance clubs sold millions of records and was largely the product of mastermind producers and their encyclopedic memories of sound samples. The Roots were a live band, high-school nerds who trafficked in sounds taken from jazz, soul, gospel—music of eras before they were born.

By all accounts, when they recorded Things Fall Apart in New York City between 1997 and 1999, the present did not belong to musicians like them. But the future, they concluded, might. Contemporaneous with the recording of Things Fall Apart, the band was involved in the production of albums by friends and musical collaborators. Each of those projects—Erykah Badu’s Mama’s Gun, Common’s Like Water For Chocolate, and D’Angelo’s Voodoo—drew from similar, less-fashionable influences, just as The Roots had done. Each, along with Things Fall Apart, is now considered a classic of both the period and a seminal album in the respective artists’ careers.

The Roots’ Things Fall Apart was recorded amid an alienating present with an uncertain future coming into view. The album submits that that future will be of our own making.

***

I’ve sketched out only the barest bones of the story of the phrase Things Fall Apart, its origin, direct descendant and stepchild. I could have also chosen the phrase’s appearance in Stephen King’s The Stand, a Joni Mitchell song or an iteration of the Batman comic book series. But I had something specific in mind with these few examples. In two books, one poem and a hip-hop record, each artist has used the phrase as an illustration of the present crumbling before us and a future not yet known. What kind of unknown and how we react to it are at the core of each text. Chinua Achebe seems to think that an unwillingness to accept the coming future is a death of the spirit, but one that could arguably be within and beyond our control. Joan Didion says we can only close the door on the past to open up the window to the future, even if we don’t know what’s outside. Yeats was terrified of what came next. The Roots argue what comes next is largely up to us. All paths are understandable, all are what make us human, the only animal cognizant of something called “a future” and our role in shaping it at all.

_____

About the author: Kevin Smokler is a writer living in San Francisco. This essay is adapted from his recent collection Practical Classics: 50 Reasons to Reread 50 Books You Haven’t Touched Since High School