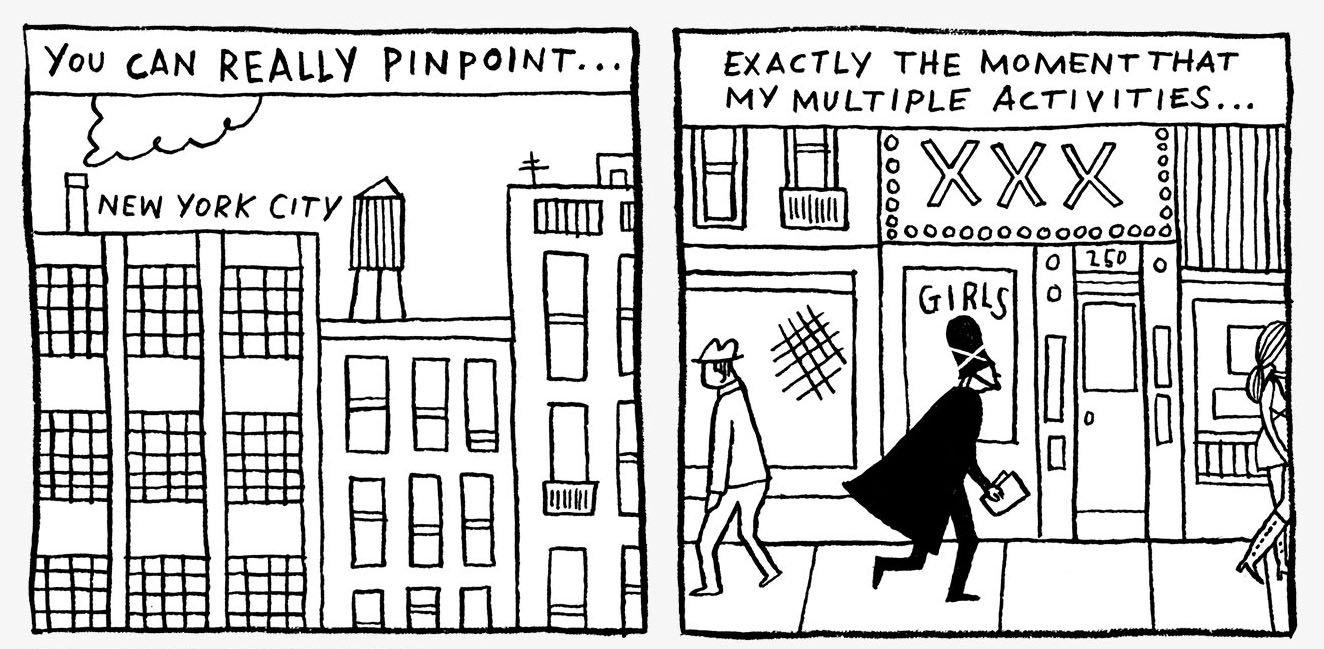

Lisa Brown is a New York Times best-selling illustrator, author, and cartoonist. Her works include Goldfish Ghost by Lemony Snicket (Roaring Brook, 2017), The Airport Book (Roaring Brook, 2016), Picture the Dead with Adele Griffin (Sourcebooks Fire, 2010), and Mummy Cat by Marcus Ewert (Clarion, 2015). She teaches in the...