Memories of Distant Mountains

Fifty years ago, the writer Orhan Pamuk tried to kill the painter Orhan Pamuk. He threw away his watercolors and brushes. He mocked his technique. He declared that Orhan Pamuk would be a novelist and a novelist alone. He lived like this for many years, years in which his success and fame exceeded his wildest dreams. But the writer could never shake the sense that he had yet to prove himself apart from the books he wrote. He believed that there was a second life he was meant to live, in a place other than New York or Istanbul, though its purpose eluded him.

One day, the writer was overwhelmed by the urge to paint again. He recognized in himself the desire that had been gagged and throttled, but never killed; he had stumbled upon the painter whom he had left for dead. He walked into a stationary shop, bought two bags of paints and pencils, and began to fill two dozen notebooks. His hand seemed to move of its own accord. One day it drew, the next day it wrote, “like someone autographing a page without even realizing they’re doing it.” There was a childlike quality to the writer’s handwriting—the upper- and lowercase letters were often the same size and wandered off the notebook’s lines—and there was something godlike in the painter’s angle of vision, the bird’s-eye view from which he peered down at his landscapes, their tiny mountains and fields, their toy houses and vanishing streets. After many years, he resolved to publish the notebooks as a single book, Memories of Distant Mountains, a testament to how the writer had freed the painter from his bondage and claimed him as his equal, his brother.

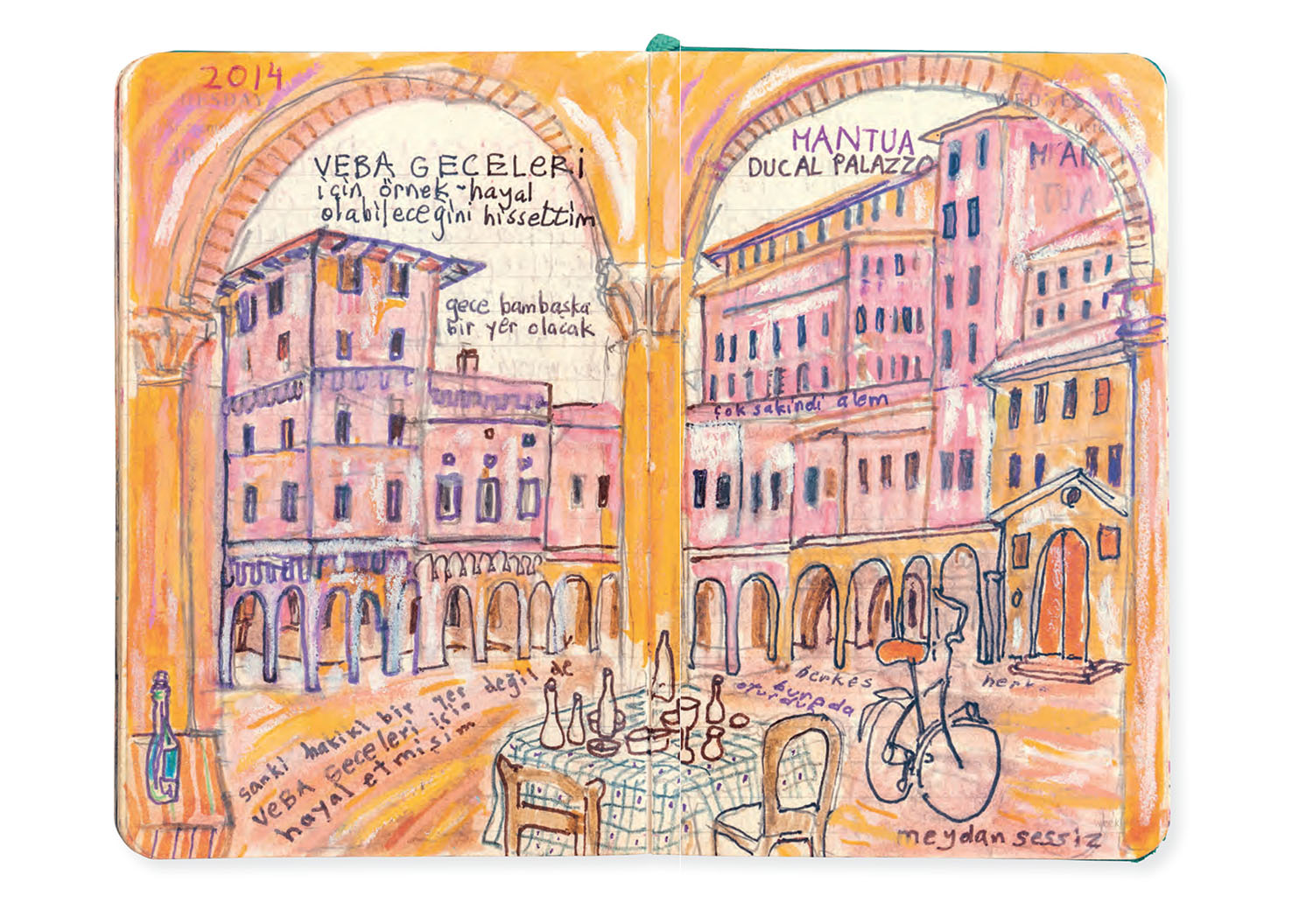

The notebooks, part mirage, part documentary, track the many meetings between Orhan the writer and Orhan the painter. The two might meet in a city, where they stand side by side and gaze at the masts of ships, domes, minarets, the smudged green of spring trees along the harbor, and perhaps a fisherman who has just cast his invisible line into the straits. They might meet on a mountain top, its snow-white peak swooning toward the sky and a line of trees silhouetted against the purple rock. They might meet behind the columns of the Ducal Palace in Mantua, pale curtains flapping in the windows of a nearby building, catching a glimpse of the hassled shopkeepers on the other side of the palazzo’s archways. Beyond the mountains, beyond the cities, lay the sea, its Chagall blue curving around the humped backs of distant islands—or, in a stormy scene, its wild gray waves leaping to meet inky drops of rain. On the edges of the painter’s vision were the writer’s words like a Talmudic frame. “As I crafted my sentences,” Pamuk wrote, “the view and the world I created in my imagination blended into each other.”

In these notebooks, the writer and the painter learned to live together—mutually vulnerable, equally sustained. The writer documented the painter’s daydreams. The painter impressed form and color onto the writer’s moods, creating a palette of pride, fear, tenderness, and longing. Details from his day-to-day life—trips to New York and India, visits from friends, artworks, films, football matches, political unrest, war—would spill into the notebooks, and the notebooks would spill into the world where Orhan Pamuk sat at his desk, visualizing his greatest novels: The Black Book, My Name is Red, Snow, Istanbul, A Strangeness in My Mind, Nights of Plague. “I sensed that this could be a template—dream for Nights of Plague,” he wrote across the skyline of Mantua. Next to a painting of an Ottoman miniature, an invented picture of an invented palace, he planned his next novel, The Painter’s Novel: “Just as I’m doing now, K will pore over the details and the margins of old miniatures held in the Topkapı Palace archives.” The writer and the painter created a life together in the notebooks that stood apart from the day-to-day, a life beyond life that was “so much broader, deeper, happier, and more enjoyable than this one.”

“Imagining a place is a way of loving it.”

In the end, it was impossible to tell which one of them had made this proclamation, so completely entwined were the two in the landscapes of the mind.