Image

You should really subscribe now!

Or login if you already have a subscription.

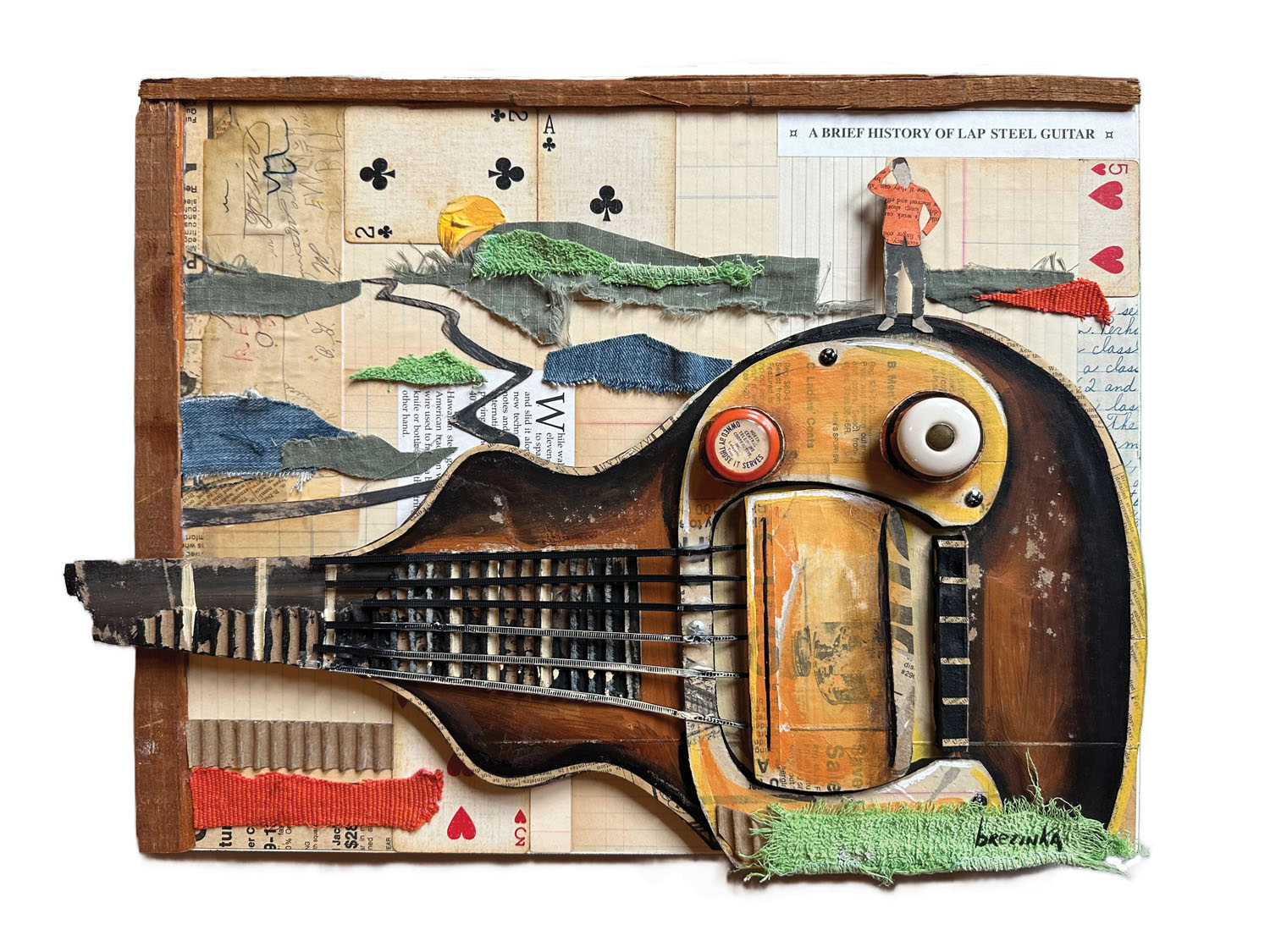

Wayne Brezinka’s work has been featured in the Washington Post, the New York Times, POLITICO Europe, and other publications. He has done album covers for Willie Nelson and George Strait.