Image

You should really subscribe now!

Or login if you already have a subscription.

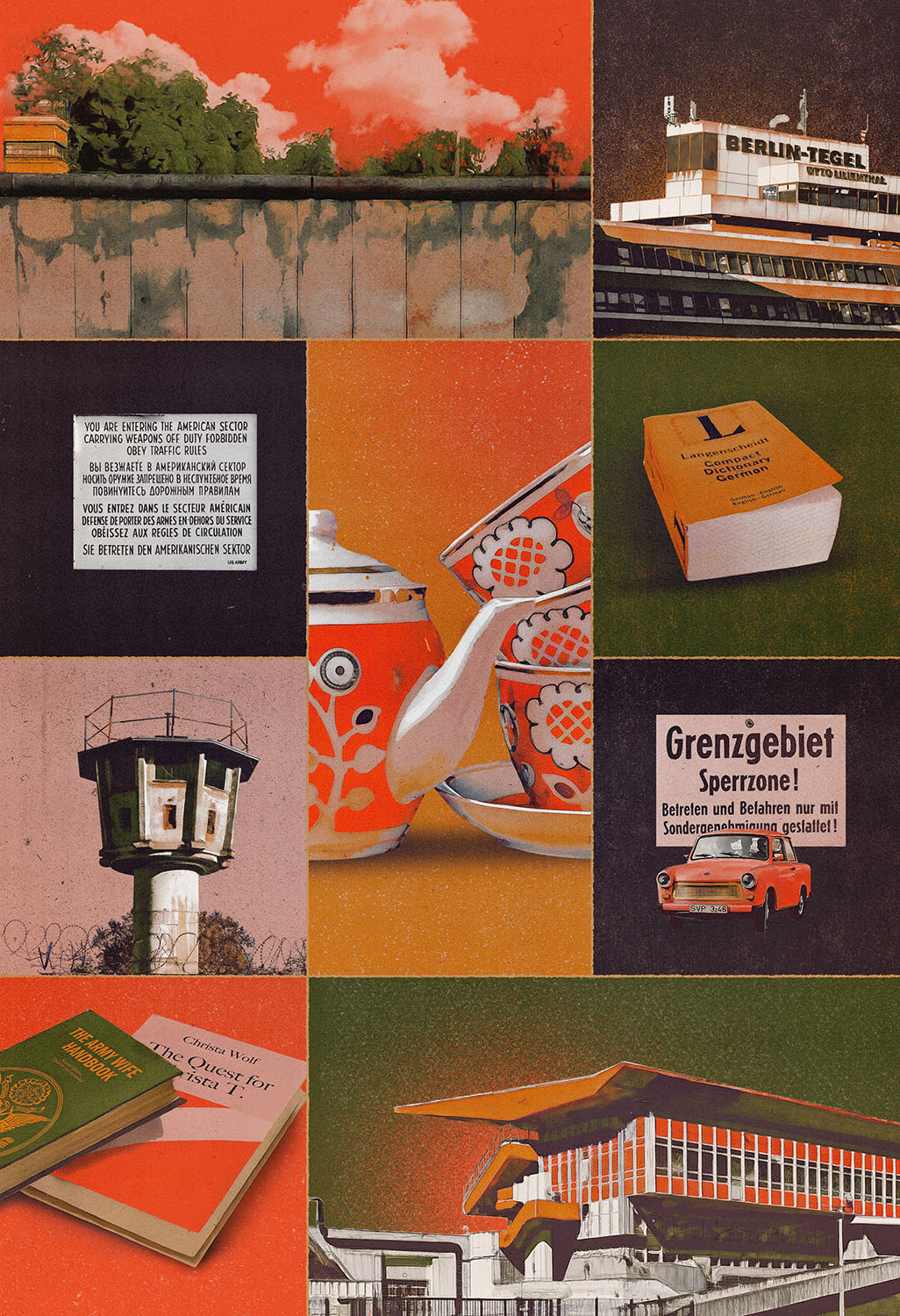

Max-O-Matic is a designer, illustrator, and collage artist based in Barcelona. His clients include BMW, Netflix, and Panenka, and his work has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, National Geographic, the Washington Post, and New York magazine.