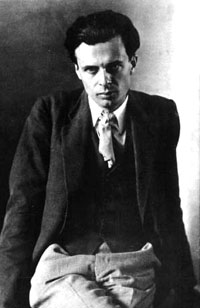

Aldous Huxley in VQR: The Philosopher as Social Critic

In VQR’s mission to become a progressive journal of national and international discussion, it was natural that this controversial intellectual was a much sought-after writer to include in the magazine’s pages. In 1931 Huxley was only months away from the publication of Brave New World, a work that put him squarely on the modernist map and solidified his iconoclast position in the literary canon. When Stringfellow Barr assumed the reins from VQR founding editor James Southall Wilson that same year, he sought to continue the original goal of the magazine: to publish writing dealing with political and artistic concerns of a wide audience, by assuring diversity of content. Eric Pinker of the James B. Pinker & Son, Inc. literary agency sent Wilson two Huxley essays on October 10, 1930, but new editor Barr replied instead, just eight days later, indicating that VQR would take what was then called “Notes on Liberty and the Boundaries of the Promised Land” for the winter 1931 issue. The essay, in which Huxley sets out to define freedom as it relates to property and highlight the impossibility of the modern class structure, is exactly the sort of diverse and prescient intellectualism VQR had become known for.

Stringfellow Barr’s letter to Aldous Huxley, December 12, 1930 (Special Collections Department, University of Virginia Library).

Barr was proud of his procurement of the Huxley piece, especially for his flagship issue. On December 12, 1930, a month before “Boundaries of Utopia” (Barr had re-titled the excessively long original title) was to appear in VQR, Barr wrote to Aldous Huxley directly: “I want to express to you personally my delight at including it in this issue; and perhaps you will pardon the intrusion when I tell you that this is the first issue of the Virginia Quarterly to appear under my editorship.” In the issue’s Green-Room (the editor’s introduction to the issue and its contributors), Barr introduces Huxley as “one of England’s foremost living ironists,” and goes on to say, “the Quarterly will champion no cause,” but “will continue to be a magazine for those to whom living is a personal art.”

This publication only boosted what had become, for Huxley, a rewarding (both financially and artistically) mode of communication. Huxley felt increasingly desperate for new ways to serve society. In January 1931 he wrote to his friend, Flora Strousse, after visiting a poverty stricken Durham coal-field: “What a world we live in. The human race fills me with a steadily growing dismay… . The sad and humiliating conclusion is forced on one that the only thing to do is to flee and hide.” For Huxley, a man who always thought of himself as an intellectual first and an artist second, the other thing to do was write essay after essay of social and literary criticism.

It is not surprising, then, that four days after writing Huxley, on December 16, 1930, Barr accepted another essay from Huxley’s agent, “Tragedy and the Whole Truth.” Barr excitedly wrote to Pinker, “I am delighted to secure it and hope you will shove some more good articles our way in the near future.” “Tragedy” would go on to figure prominently in Huxley’s seventh collection of essays, Music At Night and Other Essays, which first appeared as a collector’s edition in March 1931.

“Tragedy” dealt with variations of artistic truth in literature. Huxley designates two poles: “tragedy” as the sentimental and shortsighted manifestation of truth, and “the Whole Truth” as the ugly but honest and more useful version. Huxley writes, “The catharsis of tragedy is violent and apocalyptic; but the milder catharsis of Wholly-Truthful literature is lasting.” His concerns in “Tragedy” were similar to those expressed by his close friend D. H. Lawrence, whose essays “Nobody Loves Me” and “The Bogey Between the Generations” appeared in VQR the year before Huxley. Both men identified in their essays what they perceived to be a vague posturing in art, an insincere sentimentality.

Around the same time Huxley was writing these essays, Lawrence, a dear friend who had once playfully schemed with Huxley to form a utopian society in Florida, passed away at the age of forty-four. Huxley felt he had lost a comrade, one with whom he shared a fiery and reciprocal relationship. Where Huxley was the skeptical man of science, Lawrence was the sensitive man of passion. Upon his death, as he collected and edited Lawrence’s correspondence for 1932’s Letters of D. H. Lawrence, Huxley wrote of him: “He was really, I think, the most extraordinary and impressive human being I have ever known.” “Tragedy,” then, in its call for artistic truth, was in some ways a tribute to his friend, who always believed in the transcendental qualities of passionate writing. At the end of “Tragedy,” Huxley cites a few of his worthy peers concerned only with the Whole Truth; among them, D. H. Lawrence.

Huxley did not appear in VQR again. In 1939, then editor Lawrence Lee wrote to Huxley’s wife inquiring about a possible contribution, but by that time Huxley had moved first to the continent and then to California, where he had finally escaped the political dismay of Europe and settled into Hollywood and a more experimental phase of his life. While Huxley’s contributions to VQR with “Boundaries of Utopia” and “Tragedy and the Whole Truth” were fleeting, they were not insignificant. VQR published Huxley when he was at the precipice of his most groundbreaking novel, Brave New World, which was a different take on utopia, as well as a slew of other works that would become influential and invaluable to British and American modernist literature.

Huxley’s original manuscripts (Papers of the Virginia Quarterly Review, 1925-1935, Special Collections Department, University of Virginia Library):

Huxley’s publications in VQR:

- “Boundaries of Utopia” (Winter 1931 issue)

- “Tragedy and the Whole Truth” (Spring 1931 issue)