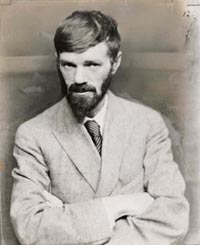

D. H. Lawrence in VQR

By Nickolas Muray, circa 1925. (International Center of Photography)

It wasn’t long after James Southall Wilson launched the Virginia Quarterly Review that D. H. Lawrence made his way into the pages of the still-nascent publication. VQR published Lawrence’s short article “The Bogey Between the Generations” in January 1929, and just a year and a half later followed with his piece “Nobody Loves Me.” The author and the young magazine were a perfect fit—a writer known for his willingness (if not stubborn insistence) on challenging social convention and a publication quickly establishing itself as a progressive, liberal voice of the American South. But the relationship was cut short by Lawrence’s untimely death in March 1930, barely a month after “Nobody Loves Me” was accepted.

One can only speculate how the relationship between VQR and the controversial Modernist may have evolved had it not been foreshortened; what we do know is that even after his death, Lawrence remained an important presence in the magazine. His work was hotly debated and fiercely defended in VQR’s pages throughout the 1930s—by such prominent writers as Aldous Huxley, Sherwood Anderson, and T. S. Eliot. And, at the dawn of the 1940s, several of his pieces were also published posthumously (with the blessing of his widow, Frieda) by VQR’s fourth editor, Lawrence Lee, including the short story “Delilah and Mr. Bircumshaw” (Spring 1940) and two plays, “The Married Man” (Fall 1940) and “The Merry Go Round” (Winter 1941).

Lawrence’s work was an important influence and flashpoint for debate for nearly a decade in VQR’s early history.

* * *

“The Bogey Between the Generations”

In 1928, D.H. Lawrence published Lady Chatterly’s Lover in Italy, much to the chagrin of his literary agency, Curtis Brown, Ltd, which thought the novel too scandalous. Lawrence wrote to his friends Aldous and Maria Huxley, in April 1928:

They are furious in that office that I publish my novel … It seems to make ’em all very mad. Why, in God’s name? One would think I advocated sheer perversity: instead of merely saying merely natural things.

There was interest in the novel from some Americans, such as publisher Alfred Knopf, to whom Lawrence dryly wrote, “I was awfully pleased to get your letter saying you didn’t find Lady Chatterly an abomination.” Lady Chatterly experienced wide success in Italy, making Lawrence a fair amount of money, but British and American houses still declined to take a chance on it. As word spread regarding its explicit content and virtuoso writing, copies of the manuscript were pirated abroad. Upset with Curtis Brown and frantically trying to secure a way to get paid for the unsanctioned copies, Lawrence found himself in the middle of a worldwide censorship scandal.

Perhaps attempting to capitalize on Lawrence’s sudden notoriety without associating themselves with the racy novel, Curtis Brown focused on his other work. The agency submitted Lawrence’s essay “The Bogey Between the Generations” to VQR’s first editor, James Southall Wilson, in summer 1928. Someone—though which of Wilson’s advisory editors is not indicated—thought it important for VQR to accept the essay; handwritten on the bottom of the soliciting letter was the simple note, “James, Do take this.” Wilson was eager to comply. He wrote back on August 22, 1928, “I have been away from my desk some weeks and the D. H. Lawrence paper ‘Bogey Between the Generations’ was sent on to me for reading. I am stopping by the office in transit to write this acceptance.”

Apropos of the resistance Lawrence was experiencing in attempts to publish Chatterly, the essay is a plea for greater frankness, for communication unfettered by the fears of what can and cannot be handled by both older and younger generations alike. In the piece, Lawrence wittily weaves his argument out of an elaborate metaphor involving an old man, his young and naïve daughter, and his daughter’s wolfish potential suitor. Sensitive to censorship and pedantry, Lawrence’s tone grows angrier as the piece progresses. While both the older generation and the younger generations personified are somewhat shortsighted, it is ultimately the older generation that takes the blame for promoting a fear of free expression, the monster that becomes Lawrence’s “Bogey.” Lawrence insists “the Bogey doesn’t and never did exist, that he is an invention of the elderly spirit, the last stupid stick with which the old can beat the young and feel self-justified.”

“The Bogey Between the Generations” was the first piece written by D. H. Lawrence to appear in VQR. It was not, however, the first appearance of the article in print. In fact, Lawrence wrote “Bogey” at the request of Arthur Olley, editor for the fledgling British paper, the Evening News. “The Bogey Between the Generations” was published in the Evening News on May 8, 1928, eight months before it appeared in VQR. In that publication it bore an entirely different title, presumably chosen by Olley (and doubtfully sanctioned by Lawrence): “When She Asks ‘Why?’” It appears Curtis Brown failed to disclose this information to VQR, which set the tone for their next interaction regarding Lawrence.

Manuscript

* * *

“Nobody Loves Me”

Increasingly sickly and reeling from sudden scandal, in fall 1929 Lawrence took a break from fiction and poetry and started sending his essays to several publications. He wrote to British literary doyenne Nancy Pearn: “I’m sending you three articles which I wrote with an eye to Vanity Fair, but I don’t know if they are suitable.” None of the three was used by Pearn, so they were proffered to VQR by Curtis Brown, Ltd. Lawrence was bitter toward the agency—which he accused of “holding up pious hands afraid of touching pitch” with Chatterly—but he continued to use them to place his essays. Agent Rowe Wright approached Wilson with “Nobody Loves Me” in early 1930.

Wilson responded in late January 1930, promptly and firmly, writing, “I shall be glad to keep and use Lawrence’s ‘Nobody Loves Me’ with the understanding that it has not and will not be produced in English until we print it.” It is likely that Wilson’s stern and anxious tone was a result of having found out that “Bogey Between the Generations” had been published elsewhere previous to the Winter 1929 issue, and that VQR was not the first appearance of the essay. So began a back-and-forth dialogue that lasted over the next three months, in which Wright brokered a deal that would allow the agency to also sell the essay to a British magazine, provided the overseas publication appeared after the VQR publication. “Any English publication after the fifteenth of June would not interfere with us,” Wilson assented.

In “Nobody Loves Me,” Lawrence indicts both New England egoists (a group he lumps with their Transcendentalist forebears) and youthful, next generation egoists for being lazy and disingenuous with the doctrine of love and acceptance. The theme of the piece finds its roots in a letter Lawrence wrote to his friends Maria and Aldous Huxley in July 1928. While living in a Swiss chalet near Gsteig, the Lawrences had been frequently visited by their Buddhist friends, the painter Earl Brewester and his wife, Achsah. Recounting one such visit, Lawrence wrote to the Huxleys:

The [Brewsters] came to tea and [Achsah] as near being in a real temper as ever I’ve seen her. She said: I don’t know how it (the place) makes you feel, but I’ve lost all of my cosmic consciousness and all of my universal love. I feel I don’t care one bit about humanity.”

Lawrence uses Achsah Brewster’s comment as the anecdote to begin “Nobody Loves Me,” in which he expresses disappointment in society’s inability to sustain compassionate understanding.

In a vein similar to “Bogey,” Lawrence’s concern in “Nobody Loves Me” is passionless impotence across generations. In the essay, the worldviews of the young and the old are depicted as hollow at their core. It is ultimately the indirect nihilism of the young on which Lawrence ruminates the most. “As a matter of fact,” he writes, “the young are becoming afraid of their own emptiness.” The jaded and frustrated tone of this essay is no surprise, considering that very few people—mentors or peers—stepped up to defend Lawrence during the Chatterly upheaval. Not only did his own agency continue to refuse to touch the novel, but his old friend, publisher Alfred Knopf, reneged on a promise to help Lawrence get a book published in the United States, saying it wasn’t worth the trouble. And the attacks did not let up, even as Lawrence’s health failed. Around the time he was writing this essay, a show of his paintings at the Warren Gallery in London was shut down by the police, and the paintings were seized due to what authorities considered to be obscene content. (Lawrence worked on most of the paintings as he was writing Chatterly.) Lawrence was bedridden with tuberculosis by this point and unable to attend the hearing. Of the whole experience, Lawrence wrote wistfully to the Huxleys, “I believe I have lost most of my friends in the escapade.”

In March 1930, while “Nobody Loves Me” was still in production at VQR, Lawrence succumbed to tuberculosis in France with his wife Frieda and his close friend Aldous Huxley at his bedside. He was just forty-five years old. He died beaten and embittered. When “Nobody Loves Me” appeared that summer, it was a fitting coda to Lawrence’s final years; the essay ends with a rhetorical question, wondering what society ought to do now that “the house of life, which is her eternal home, is empty as a tomb.”

Manuscript

* * *

Lawrence’s Posthumous Publications

After D. H. Lawrence’s death, his widow Frieda moved permanently to New Mexico, but the controversy that dogged her husband in his final years now followed her. But VQR, despite a succession of editors, never waivered in its support. In 1931, the magazine published an essay by Aldous Huxley, in which he referred to Lawrence (along with Proust, Gide, Kafka, and Hemingway) as “five obviously significant and important contemporary writers.” Two years later, Sherwood Anderson published an impassioned tribute to Lawrence. It began:

The charm, the wonder of D. H. Lawrence is just this—that you take him or you leave him. For you he is or he is not. He’s yours or he isn’t. You have a feeling that he never really cared, not about that. I mean that he never really cared about too much vulgar being taken. There was something for which he did care. Caring was a strong, a living impulse in him.

He was a man absorbed and intent. What man would not prefer to live his life so?

T. S. Eliot, ever the traditionalist, was less sold on Lawrence’s push toward innovation. Eliot nevertheless acknowledged Lawrence’s “genius” and spoke against those who regarded him as a mere sensualist. “Lawrence lived all his life, I should imagine on the spiritual level; no man was less a sensualist. Against the living death of modern material civilisation he spoke again and again, and, even if these dead could speak, what he said was unanswerable.”

Aldous Huxley, “Tragedy and the Whole Truth”

Sherwood Anderson, “A Man’s Song of Life”

T.S. Eliot, “Personality and Demonic Possession”

VQR also sought to build a critical defense of Lawrence. In 1937, John Hawley Roberts’s “Huxley and Lawrence” established the importance of the friendship between the two writers. The editors also fiercely opposed William York Tindall’s bitterly ironic biography D. H. Lawrence and Susan His Cow, published by Columbia University Press in 1939. Particularly scandalous was Tindall’s assertion that Lawrence’s fascination with authoritarian protagonists who were natural leaders betrayed a hidden fascism born from the kind of belief in blood superiority then ravaging Nazi Germany. VQR editor Lawrence Lee called on Frieda to denounce this charge personally. “As for his being a Fascist,” she wrote, “that is bunk”:

He was neither a Fascist nor a Communist nor any other “ist.” His belief in the blood was a very different affair from the Nazi “Aryan” theory, for instance. It was the very opposite. It was not a theory, but a living experience with Lawrence—an experience that made him love, not hate. He wanted a new awareness of everything around us. Fortunately we have more ways of knowing than merely through the intellect, but Professor Tindall does not know this.

To further evidence VQR’s commitment, Lee requested any unpublished manuscripts that might be suitable for the magazine. “I need not tell you,” he wrote Frieda, “that if there is any unpublished work of your husband’s we would be most happy to have the privilege of making a publication offer for it should it be work which we could publish.” So began a frenzied correspondence that lasted just over a year and resulted in the publication of a previously unpublished story and two previously unpublished plays—all within the span of four issues.

Though Frieda sent the short story “Delilah and Mr. Bircumshaw” a month after Lawrence Lee’s initial letter, it took a bit of prodding to convince her to send the plays. Infamous for simply ignoring business matters about which she was uncomfortable, Frieda did not respond to letter after letter from VQR over the next three months. Finally, just days after receiving a third letter of inquiry from the magazine on December 8, 1939, Frieda confessed to Lee her hesitation: “I am afraid to send the plays as I have one copy each.” Lee asked her to have copies made and included a check for $15 so that she might do so.

With this gesture, Frieda was quick to act. On December 29, 1939—just eight days after Lee sent the check—she wrote to regale him with her efforts to secure and send the long-awaited plays: “We went up to my other ranch to-day, an adventure, as it is nearly 900 feet high and deep in snow, to get the plays. —We made it—Now I will have the plays typed and send them to you.” With the disclaimer that Lawrence may “have rewritten them if he had seen them again in his lifetime,” Frieda enclosed three plays: “The Fight for Barbara” (which, because it had been previously published by Argosy under the title “Keeping Barbara,” would not make it into VQR), “The Merry-Go-Round,” and, with its first six pages missing, an untitled play that would later be published by VQR as “The Married Man” (an alternative to Lee’s suggested title, “With a Little Love”).

With the plays in hand, and finding them worthy of attention, Lee expressed to Frieda an interest in having the works copyrighted in her name and—following their debut in VQR—getting them published elsewhere. Frieda agreed in a letter on January 26, 1940, but not without first noting Viking Press’s right to them, and revealing personal dissatisfaction with their treatment of her late husband’s work:

I got your letter, and am very grateful to you for the trouble. Now the only trouble may be Viking who has a right to all of Lawrence’s work. But they never wanted to publish these plays and there is no love lost between them and me. I consider they treated Lawrence’s work badly … I wanted to leave the Viking but it would be so much trouble. It seems as if they did want Lawrence to be widely known. It is all a mess for Lady Chatterly, we never got a cent in America. The Modern Library wanted to take over Lawrence but did not want to quarrel with Viking. I am telling you all my woes which may be my own fault because I don’t want to give so much time and energy to this fight, I prefer feeding the chickens and baking bread.

Lee approached Viking with his proposal, and the publisher’s acquiesced, giving “clearance to the whole affair.” Four months after receiving the go-ahead from what had been Lawrence’s primary publisher, Lee wrote Frieda on May 24, 1940, to tell her that the plays would be published by E. P. Dutton and Company—though Dutton failed to make good on that promise. Lee also vowed to give Lawrence’s works “as much publicity as [VQR’s] advertising budget permits.” Most notably, Lee wrote, “Our present style of printing would not permit a reasonable presentation of the plays, and for that reason we would have to go to special costs to print the work in a style of its own within our pages.” To address the problem, “The Merry-Go-Round” was published in Winter 1941 as a special supplement.

Frieda was delighted by the efforts. “I would see about it being more widely known,” she confessed, “but I understand so little of the business end of it.” Frieda was pleased to have the wide audience and staunch defense afforded by VQR.