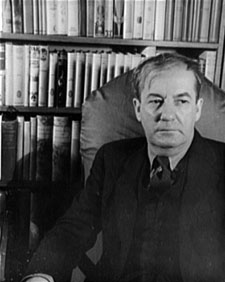

Sherwood Anderson in VQR

A literary icon of the 1920s—best known for his psychologically rich tales of Midwestern life in such works as Winesburg, Ohio and Poor White—Sherwood Anderson received a surprising letter of rejection from VQR in August 1928. Managing editor Stringfellow Barr’s rationale for declining Anderson’s submitted short story was to the point:

we [at VQR] do not print fiction or at least we have not done so except on very rare occasions … There is nothing to say about the story, except that I enjoyed it, as I do so much of your work, as I have explained the basic policy of the magazine is involved here.

Instead Barr encouraged Anderson to consider writing essays for VQR: “We would give a great deal to secure from you an article.” Barr eventually succeeded in publishing two of Anderson’s nonfiction pieces: “J. J. Lankes and His Woodcuts” (Winter 1931) and “A Man’s Song of Life” (Winter 1933). Both articles were aesthetically incisive reviews—one analyzing the work of artist J. J. Lankes, the other reviewing recent books about the life, work, and correspondence of D. H. Lawrence—and were the only pieces Anderson published in VQR.

* * *

In October 1930, a mutual friend of Barr’s and Anderson’s suggested that Anderson write an article about J. J. Lankes’ woodcuts—prints which eventually appeared in Anderson’s own works and which resonated with the writer’s small-town sensibility of rural life.

Agreeing to write about Lankes, Anderson drafted an article in November 1930, detailing “what [he] felt about the man and his work.” Barr, known to be playful in his correspondence with literary friends, wrote back stating, “You’re a brick. I knew you would!” after receiving Anderson’s manuscript.

Published in the January 1931 issue of VQR, Anderson’s article portrays Lankes’ artwork as revealing “something significant and lovely in commonplace things,” even during the “spiritually tired time” of the early 1930s.

Lankes’ artistic collaboration with Anderson, as well as with Robert Frost and Beatrix Potter, helped set him apart as “one of the very significant artists of [his] day.” Like Anderson, Lankes was a homegrown American talent, intent on exploring the question of human significance in the all-over scheme of nature. As seen in “J. J. Lankes and His Woodcuts,” Anderson’s admiration for the agrarian lifestyle, specifically with what he termed “the beauty and wonder of everyday life,” was coming into sharp focus during those early years of the Depression.

Channeling his characteristic casual tone, Barr wrote to Anderson in December 1930, presenting him with payment and praise for the Lankes article: “Here’s thirty bucks signed by the Managing Editor. I wish I had the guts to add a zero but I am extremely middle class in money matters and still dread forging. It was … swell of you to write the article—in short, you are what New York calls a swell gent.”

In September 1932, Barr, now editor of VQR, similarly described Aldous Huxley’s edition of The Letters of D. H. Lawrence as being “swell.” The book was, in Barr’s opinion, in dire need of a worthy reviewer. Requesting that Anderson write a review about Lawrence’s letters as well as three newly published books about the writer’s life and works, Barr humorously wrote, “Damn it, somebody ought to talk about Lawrence who is spiritually capable of understanding him … You do like Lawrence, don’t you? In the nature of things you must.”

Apparently, Anderson was as equally enthusiastic about Lawrence, dashing off a first draft of his review just a day after receiving the books. After proofing the initial manuscript, Barr wrote to Anderson stating, “so far from ‘merely liking it,’ as you say you do, I—and my associates—am crazy about it.”

Published in VQR’s January 1933 issue, “A Man’s Song of Life” praised Lawrence for his “nice clean maleness” during a debilitating and emasculating era of war, death, and turmoil. Terming Lawrence “the finest proseman … one of the most truly male men of our times,” Anderson made a theoretical case for Lawrence’s literary innovations, especially concerning his efforts to push the thematic envelope and to situate his writings in the modern era.

Stringfellow Barr’s Letters to Anderson

(Letters and manuscripts are from the papers of the Virginia Quarterly Review, 1925–1935, Special Collections Department, University of Virginia Library.)