Thomas Wolfe’s Final Journey

On September 15, 1938, Thomas Wolfe, author of the novels Look Homeward, Angel and Of Time and the River, died unexpectedly at the age of thirty-seven. For the literary world, the death of the talented and ambitious young writer was a profound and tragic loss. As the New York Times observed in an unsigned article the next day

His was one of the most confident young voices in contemporary American literature, a vibrant, full-toned voice which it is hard to believe could be so suddenly stilled. The stamp of genius was upon him, though it was an undisciplined and unpredictable genius… . There was within him an unspent energy, an untiring force, an unappeasable hunger for life and for expression which might have carried him to the heights and might equally have torn him down… .

Many publications echoed these sentiments, including Time in their Sept. 26, 1938 issue:

The death last week of Thomas Clayton Wolfe shocked critics with the realization that, of all American novelists of his generation, he was the one from whom most had been expected. He had almost finished his third novel when he contracted pneumonia in Seattle two months ago and was apparently recovering when an infection spread to his kidneys and heart. Rushed to Johns Hopkins hospital in Baltimore, he was operated on twice during the week, [and] died of an acute cerebral infection… .

VQR had published one of Wolfe’s earliest stories and the passing of this vital literary figure prompted VQR to solicit another. Nine months after Wolfe’s death, the Summer 1939 issue of VQR contained the last words Wolfe penned, an excerpt from a journal called “A Western Journey,” written just weeks before he died.

* * *

On October 4, 1938—just nineteen days after Wolfe’s death—VQR’s managing editor William Jay Gold wrote to Elizabeth Nowell, Wolfe’s literary agent, to inquire about obtaining a piece by Wolfe even though “probably every magazine in the country is looking for stuff by him.” He wrote

What is the situation on Thomas Wolfe manuscripts? That sounds cold-blooded and vulture-like, I know, and I do find it a bit difficult to write about it like this. All of us here were deeply sorry and shocked to learn of his death, and to me it came almost as a personal tragedy, just as his books always hit me with a tremendous personal impact …

Nowell replied to Gold’s request a few days later: “I am planning to go through the crates of script which he left and am going to make an inventory of it all with [Maxwell] Perkins, Wolfe’s literary executor.” This was, no doubt, a challenging task given Wolfe’s notoriously illegible handwriting. Indeed, several months passed before Wolfe’s affairs were sufficiently in order to allow Nowell to respond with good news. On Feb 1, 1939, she wrote to Gold:

I now have something which I want to ask you about—the very last thing of all that Wolfe ever wrote, finishing it just three days before he contracted pneumonia. It is called “A Western Journey” and is a sort of diary of the motor trip which he was taking in the west. He had intended to expand this journal, probably into a whole book, but naturally never got to it… . In form, it is a sort of diary, but its chief merit is the very lovely lyrical description and the individuality which was so markedly Wolfe’s all through it.

Gold responded cautiously without promising an acceptance, but admitted that “we do want very much to have something by Wolfe, and this does look like our meat.” He formally accepted the piece just a few days later; despite VQR’s long relationship with Wolfe, it would be just the second piece VQR had ever published of his, the first being the short story “Old Catawba” in the Spring 1935 issue. Upon hearing of the piece’s acceptance, Nowell remarked on the way VQR had bookended Wolfe’s career:

You know that “Old Catawba” piece was the first thing of Wolfe’s I ever sold as an agent; and “The Western Journey” will almost undoubtedly be the last. In fact, “Catawba” was one of his earliest magazine pieces published.

* * *

Thomas Wolfe in June 1938. (Photo by Edward Miller. Thomas Wolfe Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.)

In the spring of 1938, Wolfe’s life was in transition—he had just severed ties with his longtime editor and friend Maxwell Perkins and publisher Charles Scribner’s Sons, joined Edward Aswell at Harper & Brothers, returned from Europe, and revisited Asheville for the first time since he had outraged his hometown with his portrayal of it in Look Homeward, Angel. During this time, Wolfe’s writing was also evolving; witness to the Great Depression and Nazi Germany’s rise to power, Wolfe wrote in February that his writing was becoming less focused on his own experiences and more socially conscious. He said that a young writer’s first work “should be a very personal one, and […] he should see life and the world largely in terms of its impingements on his own personality.” But encounters with people during his travels had changed his thoughts about the goals and duties of literature: “since then I have never felt the same way about love or art or beauty or thought they were enough.” His writing was about to take on a new scope, a global perspective. This change is perhaps best characterized by a note he wrote to Elizabeth Nowell in May 1938:

I am tired, but otherwise I have not felt such hope and confidence in many years. It may be that I have come through a kind of transition period in my life—I believe this is the truth—and have now, after a lot of blood-sweat and anguish, found a kind of belief and hope and faith I never had before.

During this period of personal and professional upheaval, Wolfe deposited a massive manuscript with Aswell in New York and then fled westward—with a brief stop at Purdue University for a speaking engagement—where he would eventually embark on a whirlwind automobile trip through all the western national parks. The trip was the idea of Raymond Conway of the Oregon State Motor Association, who suggested to Edward Miller, the Portland Oregonian’s Sunday editor, that they attempt to show how cost-effectively a motorist could visit “the Western national parks within the time limits of the average man’s vacation.” To that end, they designed a trip to visit eleven national parks in just two weeks, passing the nights inexpensively in roadside lodgings. Conway and Miller had taken similar journeys that had resulted in travel articles for the Oregonian. Around this same time, a senior editor at the paper pitched to Miller the idea for a story about Thomas Wolfe, who was coming to the Portland area to search for some relatives. Miller responded, “Who’s Thomas Wolfe?”

Miller quickly learned who Wolfe was, and the two projects soon became one. Wolfe was eager to participate in the excursion. He wrote to Elizabeth Nowell on June 15 to say that he was about to embark “on what promises to be one of the most remarkable trips of my life.” In an interview with the Seattle Post-Intelligencer two days later, he told a reporter, “I’ve spent a lot of time in Europe, and I’m just beginning to realize how much I’ve been missing in not seeing my own country.”

On June 20, 1938 Conway and Miller picked up Wolfe, who had never learned to drive. Miller described Wolfe at the start of the trip:

He was wearing a tan summer suit destined to becomes mightily wrinkled. In a single collapsible bag he carried a pencil and ledger. With these he nightly wrote the entries that became his thin and final volume, A Western Journal.

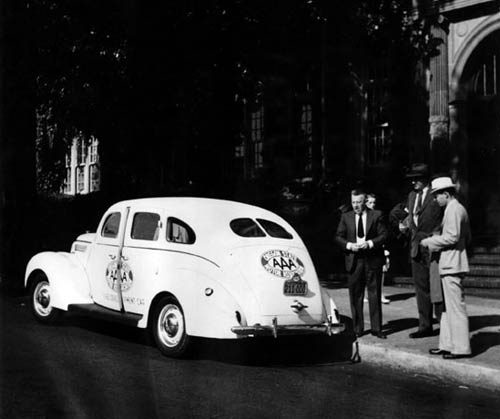

Raymond Conway, Thomas Wolfe, and Edward Miller gather around their “Travel Development Car” before beginning their trip in Portland, OR, June 20, 1938. (Thomas Wolfe Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, NC.)

In thirteen days, the trio passed through Crater Lake, Yosemite, Grand Canyon, Yellowstone, Glacier, and a half-dozen other national parks. They covered more than 4,500 miles, Conway and Miller switching off at the wheel every hundred miles while Wolfe squeezed his six-foot-six-inch frame into the back seat. Despite the physical discomfort of being confined in the car, Wolfe was by all indications having the time of his life. Miller would later write

Tom told us that he had spent more time with the two of us—that is, steady-diet time—then with any person or persons since he was in the teens. And when you keep company with any one for two weeks steady, you get to know them rather well. And between Conway and myself, Tom put in a good deal more time with me because we hit for the beer counters while Conway was sleeping or keeping his books.

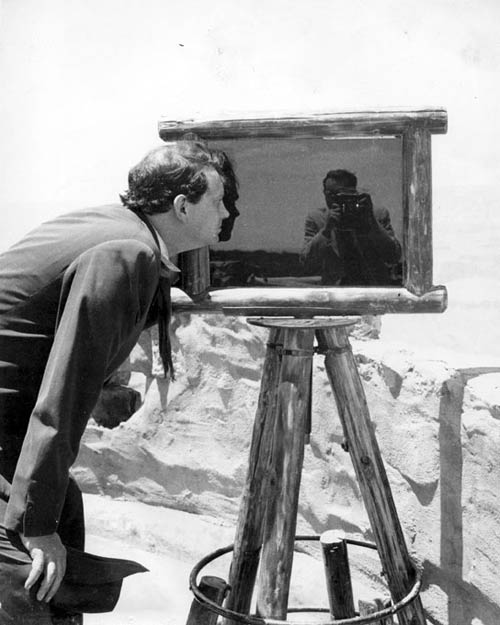

In addition to delighting in the companionship, Wolfe was enthusiastic about the scenery. This enthusiasm is abundantly evident in his decision to refer to the Grand Canyon as the “Big Gorgooby,” a decision that would later thoroughly confuse VQR’s managing editor William Jay Gold, who asked, upon reviewing the manuscript, “Was gorgooby simply the result of a mistake in deciphering Wolfe’s handwriting? Or did Wolfe actually think of the Canyon in this splendid term?” Miller clarified the issue in a letter:

This was Wolfe’s pet nickname for the Grand Canyon. I would say that the spelling should be “Gaboochee”. Conway prefers “Gooboocheee”. You can take your pick. It was Wolfe’s own invention and he said it over and over again to his great joy and satisfaction.

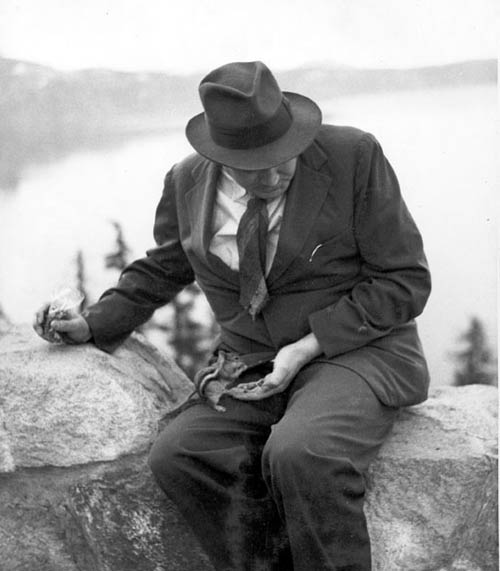

Thomas Wolfe feeds a chipmunk, Crater Lake National Park, Oregon, June 20, 1938. (Thomas Wolfe Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, NC.)

The trip ended on July 2, and, upon checking into his hotel, Wolfe received a message from his editor Edward Aswell praising the manuscript that Wolfe had given him in May. Aswell wrote that “when you finish you will have written your greatest novel so far.” The day after receiving this welcome news, Wolfe wrote to Elizabeth Nowell describing his trip in ecstatic terms and indicating his intention to celebrate Independence Day by “buying some firecrackers and spending to-morrow in H. M.’s Canadian town of Victoria, B. C.” Though the trip must have been exhausting, Wolfe seemed refreshed. On July 4, he wrote back to Aswell:

I am feeling much better already. Although I have traveled ten thousand miles, five thousand in the last two weeks, and seen hundreds of new places and people. My fingers are itching to write again.

Wolfe at the southern rim of the Grand Canyon, June 23, 1938. Miller is visible in the reflection. (Thomas Wolfe Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, NC.)

Unfortunately, Wolfe’s good fortune and good spirits did not last. At the point when he was most exhilarated with life and most confident in his writing, he fell ill—as Nowell posits—by sharing “a pint of whisky which he had bought with ‘a poor, shivering wretch,’ who probably had influenza” on the boat from Victoria to Vancouver. Wolfe biographer Joanne Maudlin points out that he probably contracted the disease in another way since his excessive smoking and drinking would have placed him at high risk for pneumonia. However he contracted his illness, Wolfe was soon desperately ill with pneumonia and tuberculosis and died less than ten weeks later on September 15.

In his introduction to “A Western Journey” in VQR, Aswell reveals that Wolfe’s journal of the trip was discovered in the hospital just hours after his death:

His mother undertook to look through his bags. And there it was—a bound ledger of the kind used in simple bookkeeping […] The ledger was full to the last page of his almost illegible penciled scrawl with the title, “A Western Journey,” at the beginning.

The publication of Wolfe’s piece generated much excitement among VQR readers, and William Jay Gold wrote to Elizabeth Nowell to inform her of the successful publicity surrounding the Summer 1939 issue, which would contain Wolfe’s piece:

I think you will be glad to know that the Publicity is doing exceedingly good work for us. Tom Wolfe readers all over the country are writing in for the special introductory offer we are making in connection with the Wolfe material, and we are really grateful to you for putting this bonanza our way.

VQR paid $115 for the piece. The full journal of the trip would later be published as A Western Journal: A Daily Log of The Great Parks Trip (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1951).

* * *

The text of “A Western Journey” is full of astute descriptions of dramatic western scenery—“the bay-bright gold of wooded big barks,” “a valley plain, flat as a floor and green as heaven and fertile and more ripe than the Promised Land,” “vast, pale, lemon-mystic plain,”—but the people of the American West fascinated Wolfe as much as the scenery. He describes women feeding deer outside the hotel, the Indian children begging for pennies, the diverse spectators at Old Faithful, the motorists who stop along the road to play with the bears, “a quaint old gal named Florence who imitates bird calls,” the man who pulls his son back from a geyser (“Don’t lean over that, I’ll have a parboiled boy”). Wolfe’s deep interest in people was also apparent to Miller, who later commented, “What stood out to me was the enormous kindliness of the man, his intense sympathy for the average, untalented, decent person.”

Wolfe admiring “Old Faithful” in Yellowstone National Park, June 1938. (Thomas Wolfe Collection, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, NC.)

Because he delighted in the land and its people, the trip’s end was melancholy for Wolfe. On the last day of the journey, he wrote:

And so, at last farewell. They are gone, and a curiously hollow feeling is in me as I stand there on the streets of Olympia and watch the white Ford flash away.

Wolfe ended his journal and, with it, added the final pen strokes to a brief but brilliant career. In just twelve years he had created a body of work of such volume and quality that William Faulkner ranked him as the best novelist amongst his contemporaries and remembered him as the writer who “had tried hardest to say the most.” With its hastily scrawled but trenchant and voluminous descriptions, “A Western Journey” stands as a final testament to that effort.

- Read “A Western Journey” from our Summer 1939 issue.

- Read Edward Aswell’s introductory “Notes on ‘A Western Journey’” from our Summer 1939 issue.

Additional Reading:

- Henry T. Volkening’s essay “Tom Wolfe: Penance No More” from our Spring 1939 issue, published in the wake of Wolfe’s death.

- Louis D. Rubin’s essay “Thomas Wolfe and the Place He Came From” from our Spring 1976 issue.

- VQR Vault - “Thomas Wolfe’s ‘Old Catawba’ in VQR” by Megan Alix Fishman & Andy Shelden.

- Wolfe’s short story “Old Catawba” from our Spring 1935 issue.