On September 10, 2014, just a few hours before dawn in Bhutan’s Chumey Valley, a teenage boy and girl hanged themselves side by side from a tree in the sloping, silvery conifer forest behind their high school. They had been caught in a relationship, which is forbidden by school rules, and were likely to be suspended. Their shared noose was the boy’s kabney, the cream-colored scarf made of raw silk which is part of the traditional attire (along with the robe-like gho) required for Bhutanese males in formal settings. At the end of a work day, it is common to see men on the street folding their kabneys with dignity and tenderness.

A health worker on the police investigative team took a photo of the hanging bodies with his phone. He sent the image to friends via WeChat. Within minutes, the grisly picture went viral. “True love” was a common pronouncement on social media among young Bhutanese, who saw the deaths as the ultimate romantic sacrifice. Older Bhutanese considered it another sign of the idyllically isolated country’s tainted bargain with modern life. Most people, of any age, saw the deaths as karma.

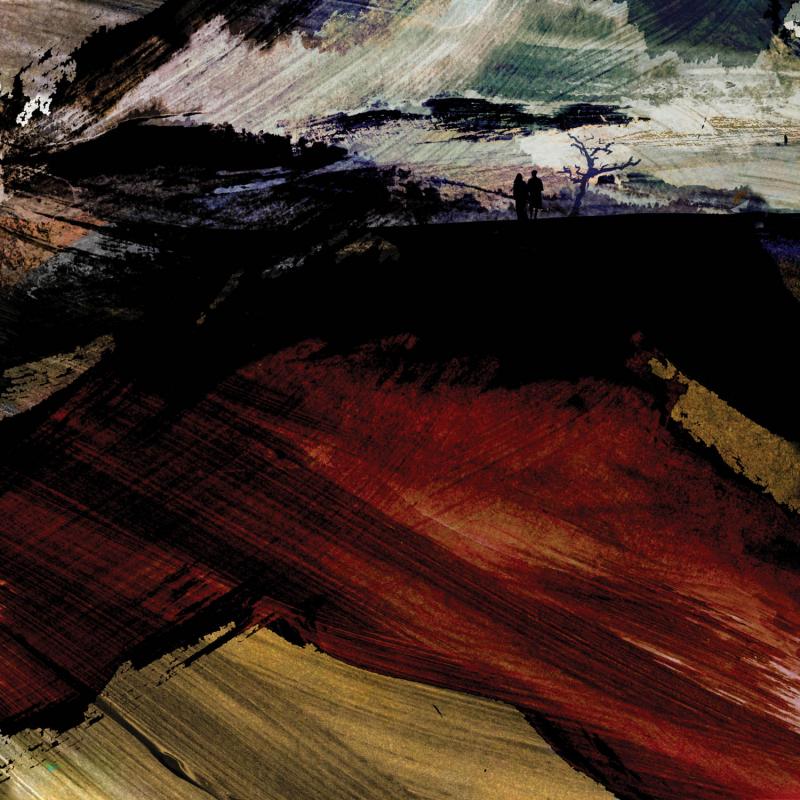

The school sits in one of four valleys in the district of Bumthang, in north-central Bhutan. Unlike the soaring Himalayan terrain one passes through while driving eastward from the capital of Thimphu, Bumthang is a textured, knitted, agrarian paradise set amid embracing hills. Bumthang is the country’s spiritual capital. Here is where Guru Rinpoche, the eighth-century Tantric master also known as the Second Buddha, subdued evil deities and brought ritualistic Vajrayana Buddhism to Bhutan. In autumn, russet fields of buckwheat spread over the landscape for hand-harvesting, and potatoes are heaped high in wooden sheds. There is an edenic, painterly quality about the place.

Shocking as it was, the double suicide was yet another example of an already troubling trend. Suicides in Bhutan had been rising sharply—from fifty-seven deaths in 2010 to ninety-six in 2013. These tragedies left grief and helplessness in their wake, but also, at times, what seemed like a collusive silence. Part of the problem, according to a 2017 report from the World Health Organization (WHO), was that “Myths and lack of awareness about mental disorders abound, as the concept of mental health is relatively new in Bhutan.” The deaths were talked around or framed in some larger cultural polemic, seldom confronted head-on for what they were.

A couple of weeks after the Bumthang suicides, I visited a small general store down the road from the school. The owner—a beefy man with a fierce expression—stood by the counter, next to the cash register and behind big jars of penny candy. With the help of a friend who translated the storeowner’s Dzongkha into English, I asked him about the deaths and how people in the valley were responding. He spoke with energy and conviction, and at times a touch of impatience, as if pained to point out the obvious.

He told me that the boy, whose family lives in the valley, had written a suicide note to his parents explaining that he and his beloved had no choice, that this was their karma, and that they were setting an example for other doomed lovers. “It’s like the whole Chumey Valley is empty because of him,” the storeowner said. “That’s why we think it’s karma.” He meant that the shock and unexpectedness of the deaths proved that the young lovers’ fate was beyond practical intervention. In Bhutan, whatever one is today as a human—the most precious form of life, because only humans have the chance to practice dharma and achieve enlightenment—is seen as being connected to one’s previous existence. In this mortal incarnation, suicide is uniquely believed to lead to 500 more lifetimes that each end the same way.

For many Bhutanese, the fact of suicide invites reflections on karma. But what if their assumptions about karmic fate were challenged? A few months before the Bumthang suicides, the Bhutanese lama, filmmaker, and writer Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche—who is a kind of spiritual rock star in the country—gave a talk entitled “In Karma We Trust,” in which he asserted that, far from being mystical, karma is a “blatantly simple” example of cause and effect. The consequences of karma, he added, don’t always materialize immediately—just as the shadow of a bird flying high in the sky fades away for a time, but reappears when it approaches the ground. What were the blatantly simple forces at work in Bhutan?

The shopkeeper suddenly shifted the conversation. “My wife says, ‘How come the people in the West are so peaceful? How come they have no problems? How come they have lots of money?’ ”

I felt a flutter of shame.

“In the West,” he said, “it seems like people all came with good karma.”

The Himalayan nation of Bhutan is wedged between China and India, is about half the size of Indiana, and is home to some of the highest mountain peaks in the world—which it considers sacred and therefore forbids climbing. When Westerners think of the country, they often think of its guiding national policy, known as Gross National Happiness, or GNH, which has acquired a fizzy popularity and has earned Bhutan a spot on many tourists’ bucket lists. The Bhutanese themselves dislike the market-driven branding of their home as a Shangri-La, because GNH has never been about personal bliss but about a thoughtful balance of sustainable development, environmental conservation, cultural preservation, and good governance. In 2013, the Bhutanese scholar Karma Phuntsho published a massive, definitive history of the country, written in part as a counterweight to articles in the popular press that, he complained, “shangrilize” his homeland.

In 2011, the WHO ranked Bhutan twenty-first among 110 countries in suicide mortality. Since then, Bhutan’s suicide rate has barely budged. But the static figure contradicts what Bhutan’s media has portrayed as a steep rise in suicide deaths. Extrapolating from news reports, the 2013 total of ninety-six deaths was likely surpassed in 2014, though the government has never published the exact number, nor the figure for 2015. In 2016, according to the national newspaper Kuensel, there were ninety-two such deaths.

For Bhutan, the year 2013 was an unnerving inflection point. That July, the capital saw five suicides in a span of three weeks: a college student, a taxi driver, an accountant, a high school student, and a recent college graduate. The next month, a wrenching sequence of child suicides made the news: A seven-year-old girl, who had told her friends on the way home from classes that she wanted to die, hanged herself from a tree; an eleven-year-old boy with perfect school attendance hanged himself at home, just after completing his science homework; a fourteen-year-old girl also hanged herself at home.

The deaths continued into the fall. In October, Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay, a media-savvy, libertarian-leaning politician who sees his mission as the modern and efficient fulfillment of a GNH vision, responded to news accounts that Bhutan’s suicide rate was merely “average” compared with the rest of the world. “ ‘Average’ is too much for Bhutan,” Tobgay said. “We should be below average, given our strong sense of community, strong family ties, friendship networks, and the fact that we’re a very well established welfare society.” And yet the toll kept mounting: a sixteen-year-old girl; an eighth grader; a military cadet; a young village woman collecting firewood; a nursing student—most of the deaths neatly attributed, by friends or in notes left behind, to such causes as school pressures or public humiliation or parents’ divorces.

On April 30, 2015, an eighteen-year-old student named Tandin Tshewang hanged himself from a tree on the road to Sangaygang, a scenic spot overlooking the Thimphu valley and a magnet for lovers. He warned of his impending death on Facebook, in the casual English locutions of his generation. “It is true that regret cums after action. I have done lots of mistake and i only recognise it today. But now i don’t have any option or ways to forgive my mistake. So all there’s left to do for me is to leave this world. So i would like to say bye bye to all my FB friends and a message to all is, don’t repeat the mistakes that I have done.”

In my mind, these cryptic news reports, and even the suicide notes themselves, failed to illuminate what was really going on. To help make sense of the deaths, I met with the Bhutanese cinematographer Tashi Gyeltshen, whose twenty-one-year-old nephew, a popular musician, hanged himself in June 2013, during a period when youth suicides were surging in Bhutan. The nephew was studying at Royal Thimphu College, but because of poor attendance was not allowed to sit for his final exams. “That must be the trigger. But that may not be the only reason for somebody to take his own life,” Gyeltshen said. “There should be much bigger reasons that the world has broken down around you.”

Gyeltshen has a reserved and appraising presence. A former journalist and editor, he had been touring the international film festival circuit with his new short feature The Red Door, an atmospheric, non-narrative treatment of his nephew’s death. We viewed the film one evening on a MacBook set on a coffee table at my rented apartment. The dreamlike story was disturbed every minute or two by the hellish din of a metal saw: Just down the street, a luxury Le Méridien hotel was going up. Gyeltshen attributed Bhutan’s recent suicides to the dueling pressures of conformity and modernization. “We cannot isolate the suicide cases. We need to look at Bhutan as a whole. I feel something is going wrong. We talk so much about the unique culture in Bhutan, the tradition, its preservation. But sometimes GNH is a big sham, the flimsy cultural cloak we wear.”

Art, Gyeltshen told me, must be at the center of GNH—and perhaps, too, at the center of the country’s conversation about suicide. The truths of people’s lives—victims, loved ones, fellow citizens, strangers—were not being voiced or heard. “Art is about telling stories. You’re a story, I’m a story. That’s how we connect,” he said. “A story is meant to be set free.”

During a nearly six-week stay in 2014, my second reporting trip to Bhutan, I heard countless suicide stories, most of which never surfaced in public. Just about everyone I met either personally knew someone who had taken his or her own life, or was one degree of separation removed. This was not because suicide was rampant, but because, as the prime minister pointed out, the social fabric is strong and wide. “We look onto the king and queen as our parents, as a father and mother. The king looks onto us as brothers, sisters, children. We want to be people from the same house,” Saamdu Chetri, a garrulous lay monk who directs the nation’s Gross National Happiness Centre, told me. Or as a physician friend explained, “In a little country like Bhutan, we are all a family. Every suicide breaks the heart and breaks the mind.”

The sense that all Bhutanese are connected isn’t a delusion. I find the most moving aspect of this place not its magnificent landscape or political idealism, but the deep, eloquent, palpable connectedness among people, the kind of connectedness that turns a minor traffic mishap into a pleasant confab of drivers and traffic police, as well as men and women and children and monks and nuns who happened to be passing by, all converging on the scene and exchanging pleasantries and jokes and enjoying one another’s impromptu company. It turns a long line at the dreary government clinic into a visible demonstration of equanimity and compassion, no one indignantly claiming special privilege or trying to cut in line. It turns a random glance between strangers on the street into conspiratorial shared smiles: a pop-up celebration of the moment, nothing more.

“In Bhutan, we all know each other,” one incessantly hears, and it proves true. My driver’s sister turns out to be the country’s most famous pop singer. My movie companion’s first cousin is the beauty pageant winner and cinema star projected on the screen in front of us. A spontaneous decision to buy cheese being purveyed from a plastic pail on a remote mountain road leads to the happy discovery that the farm woman selling the cheese is my travel companion’s wife’s second cousin.

Accompanying this stitched-togetherness—or, perhaps, abetting it—is an abundant sense of time: for leisurely conversation, never truncated by a glance at a watch or cell phone, but also just for life. Scornfully comparing their culture to what they perceive as the foolishly driven American lifestyle, many Bhutanese informed me that, “In the US, it takes two weeks to schedule an appointment with your best friend.” I concluded that Bhutan was a village masquerading as a nation. The small and large serendipities that emerge from its connectedness are revelatory to an outsider; for the Bhutanese who actually live it, what the West dismally labels “social capital” is nearly incalculable.

All this made Bhutan’s suicide wave perplexing. But I was drawn to it for another reason as well: I had lost my brother Michael to suicide ten years earlier, and knew well the endless half-life of that particular catastrophe.

People who are left behind by suicide have a great need to talk about it—a need that is relentlessly rebuffed in face-to-face conversation. In her 1999 book Night Falls Fast, clinical psychologist Kay Redfield Jamison wrote: “Death by suicide is not a gentle deathbed gathering: it rips apart lives and beliefs, and it sets its survivors on a prolonged and devastating journey. The core of this journey has been described as an agonizing questioning, a tendency to ask repeatedly why the suicide occurred and what its meaning should be for those who are left.” For me, a line from an academic anthropology text, oddly enough, succinctly conveys suicide’s complicated fallout: “ ‘[W]hat I do to myself I do to you, and what I do denies the bonds between us’…yet, the opposite also holds true—‘what I do affirms the bonds between us.’ ”

In my interviews, I openly mentioned my own acquaintance with this tragedy, partly as a strategy to gain trust through shared loss but mostly to make common cause. At first, I worried that I was drawn to write about the Bhutan suicides for solipsistic reasons. Whenever I walked past the Junction Book Store, a bibliophile’s paradise in the middle of Thimphu, I was stopped cold by the little chalkboard in front, on which was written a quote from Anaïs Nin’s Seduction of the Minotaur: “We don’t see things as they are, we see them as we are.” Was I using Bhutan for my own purposes? Eventually, I came to the conclusion that it didn’t matter—sorrow is the great solvent, and among the things it washes away are decorum and official story lines.

At the same time, I never lost sight of the fact that Bhutan is an utterly different culture than mine, and I wondered how authentic the emotional commonalities really were. Based for centuries on subsistence agriculture, Bhutan was now in the throes of transformation. “The nation is on a fast track towards becoming a market-driven competitive consumeristic society,” the 2017 WHO report said. Or as an educator told me, “We have gone through in twenty to thirty years what it has taken other countries centuries to go through.” During the early 1960s, the current prime minister’s mother was one of tens of thousands of laborers who built the first modern road linking Bhutan to India. Around that time, the Gross National Product per person was $51. Life expectancy was thirty-three years. There was no electricity, no postal system, no telecommunications. It was an almost medieval era.

By 1999, Bhutan had introduced broadcast television and the internet. In 2008, it held its first democratic election, after a century of absolute monarchy. And now young people, who in earlier days could rely on a dull civil service sinecure but now faced a merciless job market, were killing themselves. A 2013 editorial in Kuensel connected the dots: “Development brings more opportunities, opportunities beget competition, competition triggers pressure to perform and do more, in some that causes depression, and depression makes people highly suicidal.”

Such clever logic belied the fact that very little was actually known about why suicides were increasing. In Bhutan, reliable statistics (which tell their own stories) are scant and methods of analyzing the numbers are not always consistent, as even health officials concede. The Ministry of Health’s Annual Health Bulletin—a comprehensive summary of health-related conditions, including some 120 causes of death—has never reported the incidence of suicide, or even printed the word. To be sure, the resources for collecting and interpreting these data are inadequate. Last year, Bhutan’s total Gross Domestic Product was $2.237 billion, a sum shy of the GDP of Enid, Oklahoma. Moreover, in epidemiological accounting of suicide, underreporting, measurement error, and other flaws are common. The WHO tries to identify and correct these aberrations before publishing statistics online. In its 2017 world health statistics data tables, the WHO put Bhutan’s 2015 age-adjusted suicide rate at 12.1 per 100,000—which, astonishingly, was lower than the rate for the year 2000, when the total was seventeen suicides per 100,000 people. (For comparison, the WHO put US suicide rates in 2015 and 2000 at 12.6 and 9.7 per 100,000, respectively.) So were suicides in Bhutan even higher before the issue became newsworthy? Was suicide such an entrenched pattern that it was invisible?

Whatever the real numbers were, by 2014, the Royal Government of Bhutan was genuinely alarmed and conducted a retrospective study of 361 suicide cases. Psychological pain—mental illness, stressful events, addiction (mostly alcohol), and domestic violence—stood out as the dominant risk factors. Two-thirds of suicides were within the fifteen to forty age group. Two-thirds were male (a common proportion globally). And 91 percent of the deaths were by hanging.

In the student cases, researchers asked relatives to recount anecdotes about the pressures of academic expectations. “The deceased was average in studies but had failed in the mid-term examinations.” “That day he looked stressed because he was unable to complete his school work as per the deadline.” “She was poor in studies and humiliated by her teacher.… It was just two days before her exams that she hanged herself with a note stating good bye to her family.”

But school performance was not the only problem. To the apparent surprise of researchers, many Bhutanese youth were burdened with unspoken pain. “[E]ven children with seemingly perfect family relationships are prone to abuse and depression,” the report said, “abuse” referring to physical, sexual, and emotional forms. “[W]e cannot ignore the fact that it does exist in our society.”

Another surprise was that, contrary to the focus on student deaths, most of the suicides were among farmers (45 percent of the total number). Living off the land carried its own lethality: meager incomes, uncertain crop yields, vanishing villages as young people migrated to cities, endemic alcoholism, and months of sleeplessness from defending the harvest fields from the depredations of wild animals (which are protected by law). A 2015 report from the Centre for Bhutan Studies & GNH Research found that farmers, the heroic mainstays of traditional culture, had the lowest levels of happiness—lower even than the unemployed.

In 2015, the government launched the country’s first-ever national suicide-prevention action plan, enlisting members of the health, education, monastic, and law enforcement communities. The plan addressed mental health care and obvious risk factors such as alcoholism, drug addiction, and domestic violence. It also set up a national suicide registry and forensic units in all regional referral hospitals, to tighten the unreliable tallies of deaths. Put simply, the plan was a direct legislative acknowledgment that many individuals were lost in the land of Gross National Happiness.

The government plan’s research focus ran parallel to the informal public conversation. Many Bhutanese with whom I spoke reflexively blamed the suicides on foreign influences: sedatives and opioids procured at the porous border with India; Korean movies and TV, with their melodramatic plots of ill-fated romance that ended in death; strange new (and expensive) bourgeois norms, such as family vacations in Bangkok (the proof promptly uploaded to Facebook), fancy birthday cakes, even kids’ sleepovers. And they talked about the breakdown of families: parents and children eating separate dinners in front of the TV, and a general failure to communicate.

The implication was that these new indulgences sapped young people’s “resilience.” “[I]t seems suicides are triggered, sometimes, by the smallest of incidents,” Kuensel observed. “Some do it because parents yelled at them, some because they see their girlfriends with another, and some are refused extra money. Suicide notes speak not so much of depression, but of self-pity, or protest against mistreatment.”

“The notion of 500 lifetimes ending in suicide is a religious idea that is not really relevant to modern Bhutanese,” a government employee told me. “But what about the prospect of dying? Shouldn’t that be enough to deter them? Why do they not realize the preciousness of life?”

In modern Western psychology, the word resilience is defined as the ability to adapt to stress. A Bhutanese friend put a local spin on the concept: Resilience, he said, is “the ability to accept one’s own karma.” In Bhutan, people see their little kingdom, sandwiched between the two most populous nations on Earth, as resilience writ large. In the 2015 action plan’s introduction, Prime Minister Tobgay wrote: “Our aspirational goal is zero death by suicide; no families, villages, communities, and neighborhood would desire anyone dying of suicide. As a society, Bhutanese are resilient. We must uphold this character and further strengthen the social capital.” Bhutanese frequently point out that the country has never been colonized. This muscular identity filters down to the family; many adults I met recounted not with horror but with a kind of gleeful swagger the beatings they had endured as children, which they insisted toughened them.

One dissonant voice in this patriotic hubris was a woman named Namgay Zam, a popular broadcast journalist and Facebook personality. Her radio show Let’s Talk About It addressed full-on the problems facing Bhutanese society, from domestic violence to gender inequality to youth unemployment. Poised and mediagenic, she was also, like most Bhutanese, frank and approachable. And she was at ease dissecting issues that most of her countrymen prefer to jocularly dismiss, in part because in this devout Buddhist culture, her religion is journalistic skepticism. “I’m an agnostic. I have been exposed to too many things. And I’ve debunked too many things. If I had lived and studied in Bhutan my entire life, there would be a certain reverence for authority, which I don’t have,” she told me. Zam launched a petition, for example, calling for laws against the nonconsensual distribution of sexual material—a response to pornographic videos shared through social media—and, news camera in tow, personally delivered the document to the prime minister.

Zam interpreted the suicides sociologically. “Earlier, collective success was viewed as elevating your individual well-being. But the collective disintegrated and now there is pressure for the individual to succeed. The country moved but the individual did not move,” she told me. She has talked to lots of teenagers, many of whom ask her for advice. “They feel as if they are not being heard. You see nice family pictures during Losar—our New Year. But parents are not having daily conversations where they’re trying to find out what’s happening in their kid’s life. It feeds into kids’ anger against society, against authority figures.”

The religious judgments that older Bhutanese bring to bear on the suicides are not part of Zam’s vocabulary. “People say it’s cowardly to take your life. But I believe that it takes a lot of courage. You must have been driven to that point to decide, in spite of everything, that you want to end your life. And where does that come from? It totally comes from desperation.” She is convinced that many of the deaths could have been averted if a person or institution had paid attention earlier to festering problems. But in Bhutan, “It’s karma all the time,” she said. “Karma becomes an excuse.”

Zam’s wasn’t the only discordant voice on the issue. In Thimphu, I visited Tshewang Tenzin, the project coordinator of Chithuen Phendey, an outpatient counseling center. A talkative, round-faced man, Tenzin estimated that Bhutan had upward of 5,000 drug addicts, many of them young teens. A former addict himself, he had lost two friends to suicide.

“My own observation and point of view,” Tenzin told me, was that “almost 75 percent of our clients have a problem during their childhood. Some of them have been sexually abused. Some of them have been traumatized by a family member. Some of them have both parents but an alcoholic father. Some of them are left by their parents to the care of relatives and they are deprived of food. Some of them, since they’ve been two years old until the age of fourteen, they have witnessed their father beating their mother almost every day. Some of them have themselves been physically abused by their father or mother. Some of them still carry the scars on their heads.”

He meant “scars” literally. “Bhutan came to the notice of the world recently, right? Maybe one or two decades ago. But until that point of time, Bhutan was an isolated place. Our grandparents always talk about how strict their parents were. When they made some mistake, their parents used to beat them,” he said. “This is a reality of the Bhutanese family. The parents themselves have been traumatized, they were treated badly when they were children, and now they have their own problems, from the minister to the sweeper. Society itself is sick.”

He paused for a moment. “I’m not saying that Bhutan doesn’t have good things. We have so many beautiful things. Even in the family, so many good things.” But the home of Gross National Happiness, he said, “is wearing a mask.”

Others explained that the native Dzongkha language, which is related to Tibetan, did not have a word for suicide—a “fact” they offered as proof that people rarely killed themselves in traditional Bhutanese society. Linguists regularly demolish this claim and its premise as the “No Word for X” meme, the assumption that when a culture doesn’t have a native equivalent of a (usually English) word, it’s a tip-off to a prevailing mindset—a patronizing contention usually applied to what we categorize as indigenous languages. The “No Word for X” meme serves well in mythmaking. In this case, it was the Bhutanese themselves who painted for me a halcyon past, based on shady linguistic logic—self-shangrilizing, as it were.

Though there might be no single word, there is a traditional Dzongkha phrase for suicide: རང་སྲོག་རང་གཅད།, pronounced rahng-sohk rahng-cheh. Roughly translated, it means “killing one’s own soul.”

In the 1980s, a mutual acquaintance called my brother Michael and me the “heavenly twins.” I was just two years older, and in our outward appearance and manner, it was clear we were siblings: both lean, tallish, dark-eyed, dark-browed, quiet, jumpy, earnest, inquisitive. Even our spiky, shorthand-like penmanship shared a strong resemblance.

Michael was a journalist who loved poetry—Robert Creeley and William Carlos Williams occupied the center of his literary firmament. He adulated the bebop pianist Bud Powell. He wrote an encomium to Fred Astaire and had something of a dancer’s lithe grace, camouflaged by physical self-consciousness. Back in the late 1970s and ’80s, he listened to Larry King’s smoky, solacing, disembodied voice on the graveyard shift of live radio, midnight to 5:30 a.m. Open Phone America welcomed all callers by their magical place names—“Hello, Defiance, Ohio.” “Hello, Gulfport, Mississippi.” “Hello, Las Vegas, Nevada.” Nation as family, American-style.

Even as a young man, he wore only long-sleeved shirts buttoned tightly at the neck. He never rolled up his sleeves, never wore jeans, or even sneakers. Things went anxiously well for a while, then fell apart. Toward the end, he described himself to me as the strongest man in the world, because his night—a severe clinical depression, so severe as to leave him catatonic at times—never turned to day. He killed himself at the age of forty-eight—a different shade of tragedy than that of the young Bhutan victims, but still a soul cut short.

One of my brother’s most damning charges against someone was that he or she was a “ghoul”: classically, a being who robs graves and feeds on corpses—in his mind, a conniver, and also an emblem of the journalistic profession. In an enthusiastic review of a new edition of Tarr, by Wyndham Lewis—a novel he often mentioned in our phone chats—he quoted an excerpt that now gives me pause. A bohemian in Paris before World War I, the eponymous Tarr confesses the details of his unhappy relationship, then turns on his amused listener and accuses him of “prying,” because the acquaintance had not vented his own ennui: “The right to see implies the right to be seen. As an offset for your prying, scurvy way of peeping into my affairs you must offer your own guts, such as they are.”

While in Bhutan and later back home in the US, I’ve circled around that tension. Do I tell Bhutan’s suicide story without telling my brother’s or its effects on me? Do I offer my own guts, such as they are? Journalistic distance, however finely calibrated or elaborately rationalized, is often a pose.

The Old Medical Ward Block of the Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital, in Thimphu, has a dilapidated air, with a cracked and pitted exterior and long, empty hallways with wood-printed, buckled linoleum flooring. The late afternoon sun was streaming into Pakila Drukpa’s small office, where I’d come to get a wider picture of the suicide wave. A thin man in a red gho, precise and austere, Drukpa, a forensic specialist, had been steadfastly investigating Bhutan’s suicides and other acts of self-harm since 2008. He flipped open a laptop to show me a typical piece of evidence: a photo of a twenty-two-year-old man, the underside of whose forearms were entirely covered, elbow to wrist, with lacy horizontal scabs and scars. When Drukpa asked young people why they cut themselves, they mostly described failed romances and broken families. He told me about a teenage girl whose relationship with a boy was exposed at school. “The teacher ridiculed her in front of the class. That evening, she was fished out of the river.”

I flashed back to other anecdotes: the perfectionist college student who hung herself from a tree after a poor presentation; the school captain and model student, adored and doted upon by his parents, who was late for assembly and, after being publicly beaten on the back by the school principal, ended his life; the young man who hanged himself because his girlfriend was accepted to a prestigious college and he was not. Shame, Drukpa said, is a salient risk factor for suicide in Bhutan. “People say, ‘I would rather die than live with that.’ ”

Interviewed in 2013 in Kuensel, psychiatrist Damber Nirola noted that most of Bhutan’s suicide victims appear to have no history of depression. Rather, he said, what characterized the deaths was “some measure of humiliation or shame to the subject.” In countries such as the United States, he added, it is common to rebel, leave one’s family, and move far away to stake a new life. “But in traditional cultures, especially small countries, it’s very difficult for a teenager or a young adult to get away from the situation, because the situation follows them there.”

Nirola is one of only two Bhutan-born psychiatrists practicing in the country. When I interviewed him, he explained that many Bhutanese are numb to their own psychological misery. Among those who attempt suicide and survive, he often sees dissociation. “Mentally, they seem to go into a state where they don’t remember what they were doing. They say, ‘I got angry and after that I don’t know what happened.’ That sort of thing. Very common.”

A few years earlier, Nirola had attended a boy, eight or nine years old, who arrived in the ward having just tried to hang himself. Nirola asked his young patient what happened, but the boy remembered nothing. “I started taking a further history and he told me that his father used to threaten him every time he took an exam. There was a fan in the house and the father used to point to the fan and say, ‘If you fail your exam I’ll hang you from that fan.’ So this poor guy actually failed his exams. He went home, and he later told me that the only thing that he remembered was seeing the fan. He came to his senses in the hospital.”

Collectivist Asian societies are “shame cultures” and individualistic Western societies are “guilt cultures”—so goes an academic platitude. But such sweeping generalizations can seem dubious; even in a shameless culture like ours, shame abounds. Still, when Bhutan’s media began addressing the country’s suicide crisis, an unmistakable note of shame—and shaming—crept into the headlines. “A Slap in the Face of Society,” “A Sin Beyond Atonement,” “Suicide—The Ultimate Cop-out.” One exception was the monthly social and political magazine the Raven, which treated the trend with a full-throated cri de coeur. “Listen to Those Silent Screams of Our Children Crying Out for Help,” one headline ran. (To be fair, the tone of Bhutan’s mainstream media has changed since then. This past July, an editorial in Kuensel, titled “The troubled,” commented on reports that, two years after the national action plan was set in motion, suicides have not dropped and may actually be rising. “It maybe [sic] time for us to understand our youth’s troubles before we rush to correct their behaviours,” the editorial said. “If we have become a society where troubles manifest in suicides, we have not done well. Not at all.”)

The English word “shame” has been traced to the Indo-European root skem-, which means “to hide.” Shame springs from the psychic need to cover that which is exposed or has been wounded. The therapist-theologian Carl Schneider pointed out that shame is protective, “for what is sheltered is not something already finished but something in the process of becoming—a tender shoot”—an interpretation applicable not only to Bhutan’s young victims but also, perhaps, to a nation itself in a vulnerable stage of development.

In psychiatric literature, guilt is construed as springing from what one did, shame from who one is. Thus, shame is unerasable. It is also inexpressible. (Survivor guilt is a form of shame.) And shame is a feeling of being shorn from society. On my first trip to Bhutan, I had been charmed by the many sayings that attested to the anchoring spirit of home. “It is better to eat a bowl of porridge at home than to dine in a palace.” “It is better to sleep under a bridge at home than to stay in a grand hotel.” But now, it seemed, the family home was falling into dereliction. And in the nation-family of Bhutan, the feeling of being lost, disconnected, abandoned—and ashamed—may have become unendurable.

Shame has no cultural bounds, of course. In my brother’s psyche, self-expression and self-obliteration were annealed. In his notebooks, self-portraits in colored markers depict an almost menacingly impassive expression—scrawled out in black ink. His later writing is likewise permeated with scathing self-doubt and defeat. Here, another derivation is relevant: “obliterate,” from the Latin oblittera¯re, or to “write across or strike out letters.” Over time, the word evolved to mean “remove from memory” and, ultimately, “remove from existence.”

Five months after my travels in Bhutan, back in Boston, I was standing one afternoon on the inbound platform in the stygian Davis Square subway station. Across the tracks, a billboard advertised the Out of the Darkness Overnight Walk, which was to take place downtown that June for those who had lost someone to suicide. The event was sponsored by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

I felt a shudder of grief and exhilaration, fear and release. I could have told the Bumthang shopkeeper that not all Americans, not even the comfortably middle class, come with good karma. A few days later, I signed up.

In this context, “Overnight” is a brilliant metaphor. It connotes darkness to dawn, anonymity, secrecy, sacredness. When I left my apartment early that summer evening, I felt a cool current in the breeze: a rainstorm was forecast. I smelled the ocean.

Thousands of people thronged in front of City Hall, a thick-walled brutalist fortress of cantilevered concrete that looms over a sweeping brick plaza, which pulsed now with music while a herring gull wheeled above. I gazed out at the walkers, thousands of them. Their faces all had a distinctive look: pain, dignity, inwardness, eyes focused just behind or beyond the immediate scene.

The walkers wore bright blue T-shirts customized on the back, so that others could see the invisible burden each was carrying: My Nephew Stephen; My Brother Daniel; Team Benjamin; Team Charlie; Team Kate; Dad; Mom. They donned Mardi Gras-style “honor beads”—a different hue for each type of loss (gold for parents, white for a child, orange for a sibling, etc.)—so that strangers who were not strangers could taste one another’s flavor of grief without having to exchange words. Most people, however, were dying to talk, and struck up long conversations without even introducing themselves, as if this tragedy hadn’t descended on me but on an undifferentiated us.

The walk covered fourteen miles. The predicted deluge arrived. In the downpour, I talked to Team Forever Young, on whose T-shirts were printed photos of twenty-three young people who had died in a few nearby towns; a woman whose husband, tormented by PTSD after a tour of duty in the Middle East, shot himself at Fort Hood; a postdoc whose father had stockpiled pills; a woman who had—almost beyond comprehension—lost a brother, a sister, and a stepdaughter to suicide. The woman with whom I hitched a sunrise ride home hadn’t told anyone in her big family that she was there in honor of their deceased mother, because to do so would flout the tacit agreement among kin not to stir up the pain and loss—in other words, to avoid stigma and shame. I hadn’t told anyone in my family, either, for much the same reason.

In the current lingo of emotional support groups, someone who has lost a loved one to suicide is called a “survivor” (a confusing term on first hearing, since it suggests somebody who himself or herself survived a suicide attempt). According to one oft-cited estimate, there are six survivors for every suicide death. The developmental psychologist John McIntosh considered this figure ridiculously low. “[H]ow much (qualitatively and/or quantitatively) does a person need to be affected by someone else’s suicide,” he wrote, “to be considered a ‘survivor’?” Knowing how the misery of a suicide death ripples out, I sometimes wonder if it casts a pall on 500 lifetimes, measured horizontally instead of vertically. As the GNH Centre’s Saamdu Chetri told me: “We are interdependent. We are interbeing. You kill yourself, you are killing all that is related to you.”

Two years after I returned from my Bhutan trip, twelve years after my brother’s suicide, I hauled up three cardboard boxes from my basement storage locker and summoned the courage to open them. They contained some of my brother’s papers, which I had hastily packed after he died. After I sliced the sealing tape and began excavating the contents of my secret cache, I felt a sensory flood of remembrance: yellowed manuscripts filigreed with golden diatoms of mold, crumbling newspapers, the dark oblong outlines of rusted paper clips on Eaton’s Corrasable Bond, the scent of my brother’s Marlboros on my fingers.

His poetry manuscripts were crisply bound, meticulously organized, assembled with an archivist’s care and pride. Reading through the papers, I realized that he never showed anyone his best poems—a few of which are, as he would say, “mighty fine.” But my reading also made me relive our relationship, by turns angry, affectionate, wary, high-humored, fractured, and ultimately helpless. On paper, his mood was contagious. Reading his late work over a concentrated few days, I felt bleak and despairing and paralyzed myself. It was a joyless place to visit, and I was glad I had a passport out. In going through his papers, I also realized, with both consternation and relief, how tangential I was in his psychic life.

I still have the fossils I found with him, fifty years ago, when we scavenged a local ravine. I was surprised to find that he had also kept a few mementos from me—notes, my edited drafts of some of his journalism, the postcard I blithely sent him from Paris in 1998—a scene from Hannah and Her Sisters, in which Woody Allen stands in a rain-splattered phone booth, wearing a signature expression of stunned despair. The printed inscription read: L’éternité, c’est long, surtout vers la fin. Eternity is a long time, especially toward the end.

Like many siblings, I denied our bonds and affirmed our bonds before he died. The same was true after he died. His suicide was long in the making, yet it broke the heart and broke the mind. In his small bedroom, I packed 252 boxes of books after he was gone. They stood in mountainous stacks through which he cleared a narrow path to the bed. He was immured in literature, but words failed him. It’s a painful story to recollect. But as I learned in Bhutan, a story, no matter how sorrowful, is meant to be set free.