Image

You should really subscribe now!

Or login if you already have a subscription.

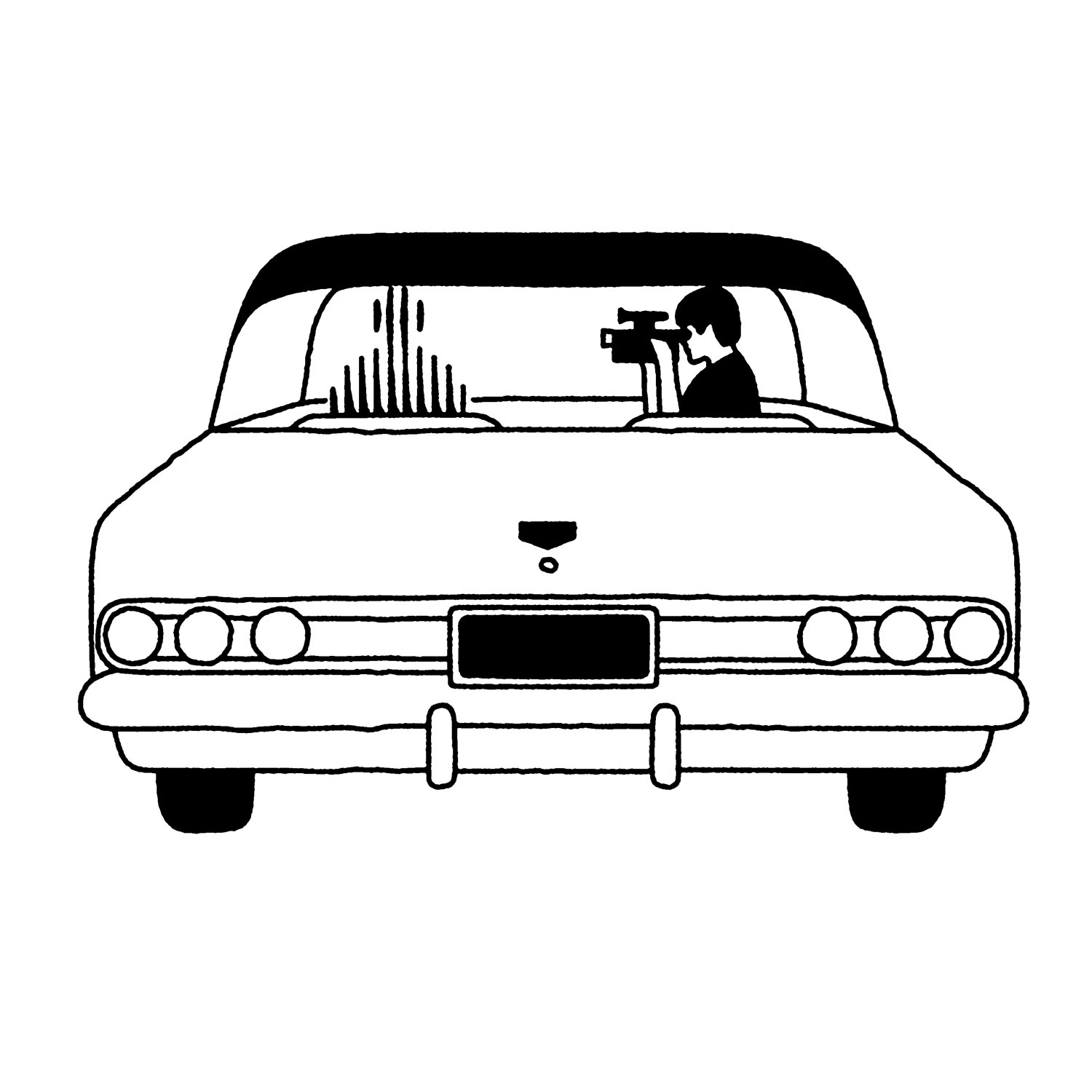

Pablo Amargo’s work has been published in The New York Times, The New Yorker, Jot Down magazine, National Geographic, and elsewhere. He has received several significant illustration awards throughout his career, including the National Spanish Award, the Golden Plaque Biennial of Illustration in Bratislava, the Gráffica Award...