Letting Go

A few years ago, I lost my marriage, and I began to recognize a common currency of loss more generally. We were all starting to emerge from the exhausting toll that COVID took on everything—security, health, faith. Educations, adolescence. Other marriages too, I’m sure. And lives, of course: mothers and fathers, friends, children. I remember meeting one man, in the rural hospital in New Mexico where I work as an emergency physician, who lost seventeen members of his family to COVID. I remember the way he sat on the stretcher, upright and composed but looking away into the distance, as though the room had no walls. I saw a lot of that sort of thing at work back then.

What do we do with the undertow of grief that remains when someone we love, or something we need, is gone? We’re taught to celebrate milestones, our achievements and additions, but are never taught how to grieve. It seems like an important skill to learn, considering that everything we love we will inevitably someday lose.

During the divorce, I told a therapist that I took comfort in knowing I could just wait out my pain. Eventually I would heal, because in my profession, that’s what wounds do. He was skeptical. Psychological wounds are different from physical ones, he said. If you’re not careful, they can create problematic scars. They need attention, and intention, he told me. You need to do something about it.

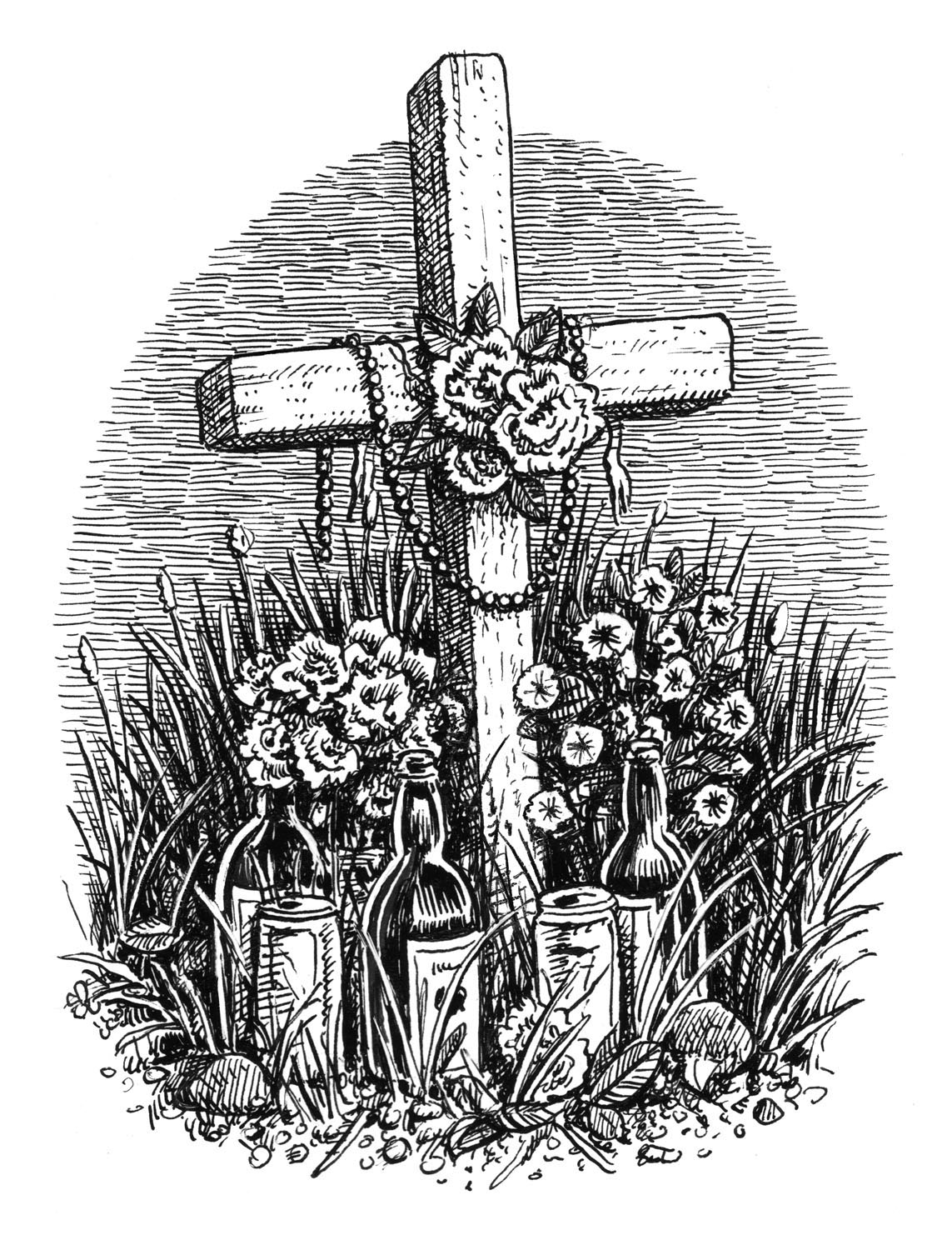

Looking for a way out of the grief, I began spending time on the back roads of New Mexico. Long, black ribbons across landscapes. I didn’t know what else to do. If you travel in the Southwest, you’ll notice the roadside crosses here, among hills and empty shoulders, at corners and intersections. They’re called descansos, which in English means “resting place.” Said to have roots in old Spanish burial processions, these memorials are erected and maintained sometimes for over a decade by families to mark the site of a fatal accident. Some of the ones I saw were simple, just white wood and a name. Others were draped with tinsel, ornaments, pinwheels, tiny lights. Each one an embodiment of loss.

I admired the courage behind the descansos, unafraid of the particular ground where something awful had happened. I tried to be unafraid too. One definition of healing, I once read, is acceptance of things as they are, and so I decided that whatever painful emotion arose, I would accept it. At the store, when I saw the wine we’d served at our wedding, I reached for it; I didn’t want to withdraw from the things we had shared. “Avoid or,” a poem we both loved had counseled: Don’t lose yourself in what might have been. There is no other life.

One day, in Albuquerque, I made a wrong turn and found myself in the parking lot of a small community theater. A poster advertised their current production—Constellations, by the British playwright Nick Payne. My wife’s favorite play. We’d never had a chance to see it. The invitation was obvious. I accept.

The play is conceptually strange, a cast of two acting out looping iterations of their lives together. Whole futures open from small variations on single moments, changing the course of everything. One critic called it Cubist. Watching it, I found myself reliving pivotal instances of our own relationship, wondering which had been the fulcrum of its ending, and whether it could have been different.

Eventually one of Payne’s characters, a theoretical physicist, observes that “in the quantum multiverse, every choice, every decision you’ve ever made and never made exists in an unimaginably vast ensemble of parallel universes.” In other words, my wife and I were still happy and secure in a million other lives together, somewhere else. My lesson was otherwise. Among untold possible lives, we had the blessings of this one: We loved lichens, and postcards, and a place called Stamboul. And, for a time,

each other.

In the spring, I returned to a mountain monastery that had been important to us. I met with a teacher there, and as I laid out the debris of my life to him, he reminded me that there really was no way around the suffering. There’s only through, he said, with a shrug. A white cat picked its way around the legs of our chairs.

Beyond a ridge near the monastery was a valley where my wife and I had once hiked. I knew that it had since burned in a wildfire, and I decided I would go and view the ashes. When I gained the ridge, I found instead an ocean of wildflowers. The silvery skeletons of burnt manzanita were trellised—every last one—with climbing morning glory.

The descansos were turning out to be good teachers, so I tried to get closer. A photojournalist named Bob Eckert has documented them, interviewing the families who maintain them. We drove out to see one that he had photographed. When he pulled over north of Abiquiu, I knew where we were. On the shoulder, he showed me a metal cross draped with rosaries. Beyond the cross, I could see the brilliant yellow cliffs that had framed our wedding, at a place called Ghost Ranch, which had been delayed a year from our legal marriage due to the pandemic. I accept.

The actual experience of putting up the memorial, Bob said, was a healing process for the family, a kind of grief ritual. In this sense, the descansos don’t just bear witness to pain, but seem to be a way through it. Cristine Legare, a psychologist who studies ritual, told me that the action is indeed powerful. “The fact that it gives us something to do,” she affirmed, “is so therapeutic.” The ability of ritualized activity to attenuate difficult emotions has been established experimentally, she explained. The significance we instantiate in the activity seems to be the secret. Rituals are “vehicles of meaning,” as one group of psychologists puts it, which establish a kind of reciprocity—we grant them their power, so that they may in turn affect us.

Legare believes that we are programmed for this. Ritual behaviors are found in every known human culture, she said, and in some animals. Elephants, for instance, journey for days to visit the bones of their dead. Chimpanzees perform special handshakes, perhaps to maintain social cohesion.

In his book Ritual, anthropologist Dimitris Xygalatas notes that one sociologist has argued that ancient shamanic rituals may have “shaped the biological basis for religion and spirituality,” and even constituted “the primary means of healing in early human societies.” Similarly, religious-studies scholar Catherine Bell has argued that, as Xygalatas puts it, “rituals offer solutions to various problems inherent in the human condition.” Including, presumably, grief.

After a while, I started seeing ritual everywhere. Baptisms, birthdays, graduations, funerals. The candles in a corner of our hospital parking lot in remembrance of a nurse we lost to COVID. And weddings, of course. Ours had been officiated by a Zen priest who incorporated an old Buddhist ritual called shasui, in which he used a sprig of pine to cast water over the guests as he said, over and over, “everything is fresh and new.”

What I needed, I recognized, was my own grief ritual. Legare told me that it should have enough formality “to imbue it with, if not sacredness, specialness.” She suggested using a script. I should select, with intention, particular items I might include, as well as a location. “Location matters,” she said. Choosing a particular place to externalize my grief meant that I could leave it there. “Not having a place for it to be,” she told me, “means it’s everywhere.”

And so I pulled my ring from the bottom of a bathroom drawer. I found our vows, and our marriage license, and I took them to the top of Gothic Mountain, in Colorado, where, in the first year of the pandemic, and a year before the actual wedding ceremony, my wife and I had married ourselves, with the dog as our witness.

There, on the blocky summit that had been our own church, I burned the marriage license. I read our vows aloud, and I burned them too. The wind swept the ash from the rocks. Then I buried my ring. When I was done, I came down from the mountain and began to walk into a new life. And in the weeks and months that followed, I found that everything was becoming fresh and new again. Moving toward whatever hurt, it turned out, was the way through.

Landis Blair is the author and illustrator of The Envious Siblings and Other Morbid Nursery Rhymes (Norton, 2019). Additionally, he illustrated the New York Times bestseller From Here to Eternity (Norton, 2017) and the graphic novel The Hunting Accident (First Second, 2017), which won Best in Adult Books at the...